What Did the “Stimulus Plan” Stimulate?

Faced with an escalating pandemic in March, the President and most governors did not want to “stimulate” the private economy. They wanted to shut it down –with stay-at-home orders and mandated business closings. That was a deliberate government supply-side crisis, not an accidental demand-side recession. People were not suddenly prohibited from buying many goods and services because they had no income. They had no income because they were prohibited from producing desired goods and services by working in certain “nonessential” jobs or opening “nonessential” businesses.

Supply-side restraints on economic activity, whether caused by prohibitive regulations or punitive taxes, cannot be fixed by having the Treasury issue more IOUs and/or having the Federal Reserve buy those IOUs by expanding bank reserves.

Federal officials nonetheless declared that what was needed was not to loosen the shackles but to enact a $3 trillion “stimulus plan.” By early August, evidently disappointed with the results of their first effort, House Democrats were proposing to rerun the experiment on the same $3 trillion scale while Republican senators suggested borrowing and spending a third as much. Both House and Senate plans include $300 billion for a second round of Economic Impact Payments, however, sending $1,200-2,400 checks to people as if it was free money from generous politicians.

Recall that the first big stimulus plan of March 27, 2020 was advertised as a way to boost consumer spending. “We want to make sure Americans get money in their pockets quickly,” said Treasury Secretary Mnuchin. The quicker they get it, the quicker they’ll spend it. The added spending, in turn, was supposed to show up as faster growth of nominal GDP which (by assuming no supply-side impediments) was expected to result in faster growth of real GDP. Yet nominal GDP fell at a record 34.9% annual rate in the second quarter, and real GDP fell at a 32.9% rate.

Mailing $1,200 checks to 159 million people, adding $600 to weekly unemployment benefits and rationing forgivable 1% loans for five years did, of course, raise personal income. Relatively small tax credits lifted after-tax (disposable) income slightly more. “Disposable personal income increased $1.53 trillion, or 42.1 percent, in the second quarter,” reports the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). Yet contrary to stimulus promises, consumer demand fell even more than income increased: “Personal outlays decreased $1.57 trillion. . . The [34.6%] decrease in outlays was led by a decrease in PCE [personal consumption expenditures] for services.”

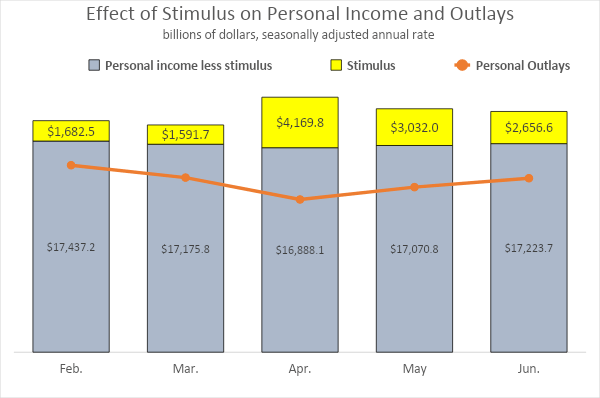

The graph retells this story on a monthly basis. Personal outlays (consumption) fell the most during April, when various stimulus checks were largest. Stimulus refers to what BEA calls “Pandemic Response Programs” that directly affect personal income (excluding corporate grants, tax breaks and loans). These federal spending programs accounted for 20% of personal income in April, 15% in May and 13% in June.

In addition to $1,200 in helicopter money dropped on 159 million adults, and subsidized PPP loans to some lucky noncorporate businesses, the “stimulus” package included longer and larger unemployment benefits –an extra $600 per week. Added to state unemployment benefits, the $600 federal checks provided the equivalent of a $24-28 an hour wage in most states. By contrast, the average wage in the leisure and hospitality industries was $16.86 in July, and falling, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

With the federal government’s $600 weekly add-on, unemployment benefits were the equivalent of working for $31-36 an hour in Oregon, Washington, Minnesota, New Jersey and Massachusetts. Why work? In June, New Jersey and Massachusetts suffered the nation’s highest unemployment rates of 16% and 17.4% respectively.

Unemployment and the economy in 42 other states, however, began to improve as soon as COVID-19 business closures and stay-home orders were partially rolled back in most of them by May 29. By August 5, the U.S. economy was expected to rise at a 20% annual rate in the third quarter, according to the Atlanta Fed GDPNow model, regardless of another Congressional spending spree. If so, that would mean the steep recession apparently lasted just 4 months.

Consumers did not buy fewer haircuts, gym memberships and restaurant meals in the second quarter because they lacked immediate income. On the contrary, disposable personal income soared as personal spending fell. Consumers bought less because (1) sellers were not permitted to sell what they wanted to buy, because (2) gubernatorial mandates shutting down many businesses made future profits and wages insecure, and because (3) people are too sensible to commit to big ticket purchases on the basis of an ephemeral windfall from vote-buying politicians.

So, what was stimulated by the stimulus? The answer is obvious. Federal nondefense spending rose at a 39.7% annual rate. Big government spending can and does grow big government.

The only conceivable rationale for repeating the latest of many failed experiments with fiscal stimulus (borrowing from Peter to pay Paul) might be to “stimulate demand.” But we just tried that. It didn’t work. It never works.