What Amazon Really Means for Small Businesses

Who doesn’t love small businesses? They embody two classic American archetypes: the little guy and the hard worker. People treat them less as individual businesses, and more as barometer of what they find good and fair in our market-driven economy. There are few more effective ways to drum up public support for or opposition to a policy than arguing that it’s good or bad for small business.

Lost in this narrative are the businesses themselves — a diverse array of individual actors rather than a monolithic symbol of economic virtue. Asking whether something is good or bad for small business limits our understanding of how firms and markets evolve.

Nothing better embodies the array of ways revolutionary technological change reverberates through the business landscape than the impact of internet retail giant Amazon on small businesses. Thinking carefully about that impact requires us to unpack the many kinds of firms we lump under the term “small business,” as well as the different functions Amazon serves in the market. Rather than a simple cause-and-effect story, we see a reshaping over time of what it means to be a small retailer.

False Narratives

Media commentary about small businesses generally falls into either what I’ll call the victim narrative or the hero narrative. Both tout the virtues of small firms, while neither helps them actually prosper.

The victim narrative sees small businesses as unable to cut it in today’s economy without help. Their prices will inevitably be undercut by retail giants and large manufacturers with their irresistible economies of scale. Implicit in this view is the idea that things used to be better, and that small businesses need to be protected to go back to this imagined golden age.

The hero narrative simply turns the victim narrative on its head. Small businesses are fighting on the front lines to save Main Street. It is therefore our civic duty to shop at small businesses, to maintain robust communities, local character, and upstanding values in commerce.

Small businesses don’t need to be protected or supported. They just need to be businesses. Many can prosper alongside larger competitors, while others will fall by the wayside.

Success and Failure

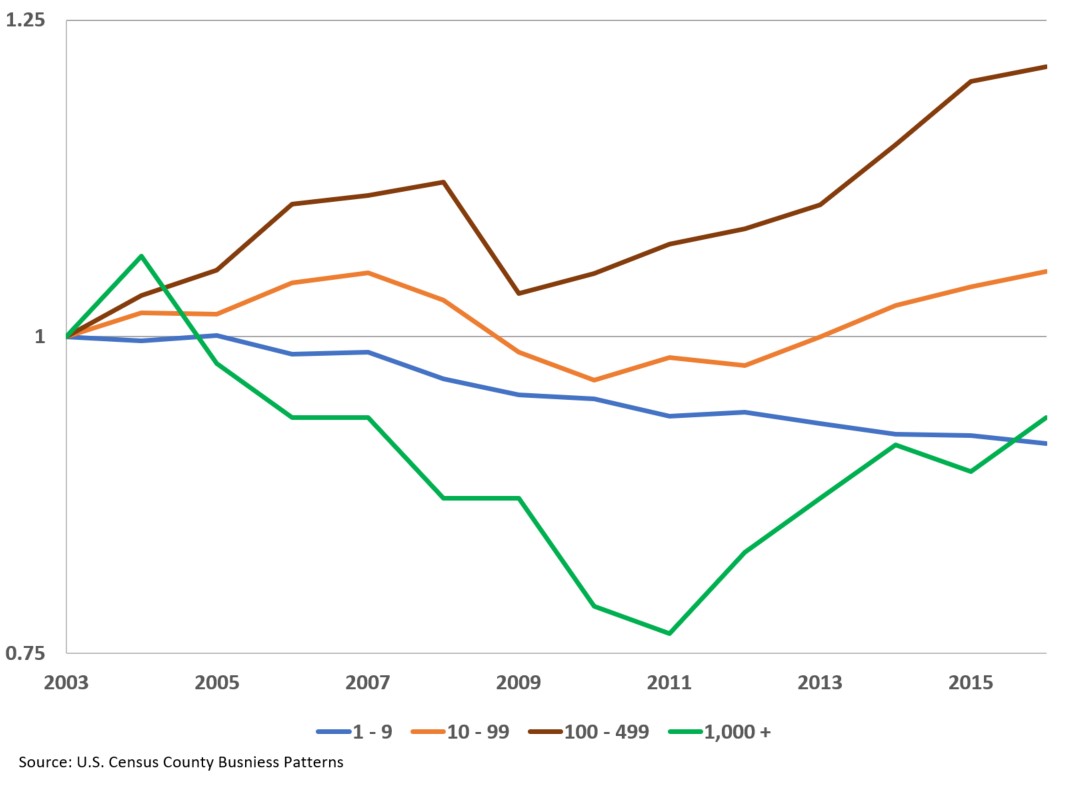

Even a quick look at the data shows that changes to the retail industry since Amazon became a competitive force cannot be explained with one simple story. The graph below shows how the number of retail firms of different sizes changed from 2003 through 2016. Each size class is set equal to one in 2003, so we can easily see the percentage by which each has grown or shrunk since that year. (I’ve omitted the data for firms with between 500 and 999 employees because large inconsistency in the number of firms from year to year suggested an error or change in measurement.)

Percentage change in number of U.S. retail firms by employment size, 2003–16

First, the numbers provide some perspective. There has clearly been significant change in the structure of the industry, but even the category with the largest drop, retail firms with one to nine employees, fell by less than 10 percent. Second, the numbers discredit the story that small businesses are under attack at the expense of everyone else. The only other size category to decline over the period was the largest firms, those with 1,000 or more employees.

These data are silent on what products the retailers sell and whether lots of firms or just a few entered and exited, suggesting a much more exhaustive look at the data would be interesting. But the chart does suggest that different kinds of retailers have had vastly different experiences with the changes wrought by internet technology.

Greater Reach Creates Larger Firms

To understand the impact of Amazon on retail markets, we must appreciate that Amazon is in two mostly separate lines of business. The first, Amazon’s direct retail operations, is the continuation of a trend toward larger stores that started long before the internet and even computers. The second line is Amazon Marketplace, which allows small retailers or even individuals to use Amazon’s infrastructure to reach anyone shopping on Amazon’s site. This represents a new development in the internet era whereby even small retailers can become global sellers.

Think about what a trip to the grocery store would have looked like 100 years ago. You would have visited a small store likely within walking distance of your home. While many consider this the golden age of Main Street, the demonstrated preferences of consumers tell us otherwise.

Twentieth-century technological advances such as the widespread use of cars and mass advertising enabled by broadcast media allowed stores to have greater reach. Consumers could learn about the stores and easily travel outside their neighborhoods to shop. Stores could grow larger and take advantage of economies of scale, providing consumers with cheaper and easier-to-navigate shopping experiences.

The internet continues this trend of greater reach by taking physical proximity almost entirely out of the equation. Customers are no longer limited by the length of a car trip when choosing where to shop. This has allowed retailers like Amazon to dwarf the size of any brick-and-mortar retailer, and exploit even greater economies of scale, once again providing cheaper prices and an even more convenient shopping experience.

Amazon’s direct-retail business line is certainly a bad development for brick-and-mortar retailers of all sizes. Mom-and-pop and big-box retailers suffer alike. (But the latter may be behind some of the decline in the largest retailers we saw above.)

It also carries some negative consequences for cities and towns, hence the simplistic small-business narratives discussed above. But when weighed against the newfound ability of consumers to have almost any product mailed to their home in a matter of days, saying that Amazon represents anything close to a bad development overall is implausible. This is the process of creative destruction at work, and though the upheaval is undeniable, the ultimate change is of great benefit to people.

Greater Reach Creates Smaller Firms Too

Amazon Marketplace is a platform that is little different from those that taken together are commonly labeled the sharing economy. For a fee, small sellers can list products that appear in the exact same search engine and use largely the same familiar payment system as Amazon the direct retailer. This enables some small retailers, previously with only a single brick-and-mortar store, reach potential customers around the globe and expand. Millions of firms and individuals sell on the platform and account for more sales volume than Amazon itself.

The platform allows other small retailers to exist where no profitable business model existed before. Suppose your lifelong dream was to make and sell bandages that display insults quoted from the plays of William Shakespeare. Even though you live in a large city, you’ve unsurprisingly found that not enough of your fellow residents are interested in purchasing such bandages to make the business profitable.

Enter Amazon Marketplace. The question is no longer how many people in your city want Shakespearean insult bandages, it’s how many people in the world want them. You can enter the market and run a profitable business, and the consumer is made better off by owning a product to which they previously had no access.

Small businesses can realize some of this benefit through their own website and some well-placed Google ad purchases. But Amazon’s status as a direct retailer already visited by millions allows the Marketplace platform to sweeten the pot considerably. For example, customers are able to use a familiar search tool and payment system, reducing search and transaction costs.

Some sellers will not like Amazon’s fees or the rules it puts in place. But for small retailers, especially those selling goods Amazon itself does not choose to carry, Amazon Marketplace may be the entire reason for their existence.

Reshuffling the Retail Deck

The question “Is Amazon good or bad for small business?” cannot get at the multifaceted changes to the retail landscape brought about by the online giant. Amazon has forced and will undoubtedly continue to force some retailers out of business. For others, the opportunities offered by the company will lead to greater profits or even allow them to be in business in the first place.

Brick-and-mortar retailers selling the type of everyday, mass-market products that overlap with Amazon’s direct retail business likely face continued hits to their market share. This category includes many small businesses as well as big-box retailers, the latter of which now face the same competitive threat from Amazon that it initially posed to mom-and-pop retailers. Technology enables greater reach, greater reach enables growth, and growth enables lower prices and greater convenience.

The second group is much more likely to sell niche products. The aforementioned Shakespearean insult bandages are one humorous example, but the combined impact of introducing these unusual products in a way that’s accessible and affordable to consumers leads to great gains in well-being.

For Amazon to find, stock, and sell niche products with limited appeal would often conflict with its model as a very large firm. The Marketplace platform allows it to enter into a joint venture with millions of small sellers, who bring their passion and specialized knowledge, while Amazon brings its unparalleled ability to reach consumers and process sales.

Amazon is no different than Walmart, Target, and supermarkets before it, giving consumers better shopping options and therefore leaving failed smaller businesses in its wake. But the revolutionary capacity of the internet to bring people together and let them find the best with whom to do business allows Amazon to provide new opportunities to many small businesses. To understand these wide-ranging impacts, we have to unpack what individual small businesses do, rather than caricaturing them as either heroes or victims in a changing world.