The WWI Agriculture Boom and Bust

Since the 2007–8 financial crisis, economists have heavily studied economic booms and busts throughout history. While each episode has its own unique features, there are common trends that recent research highlights.

A new NBER working paper by Matthew S. Jaremski and David C. Wheelock studies the agricultural boom and bust surrounding World War I. Using bank-level financial and county-level agricultural data, they show how risky lending behavior amplified the boom and bust.

The authors find three main results. First, rising crop prices encouraged new banks to enter and existing banks to expand their balance sheets. New lending, especially through new banks, is how the agricultural shock propagated through to the real estate market. Those new banks were especially likely to fail.

Second, the state-chartered banks, which were regulated at the state level and generally faced fewer regulations than nationally chartered banks, responded more to the boom. In general, regulated banking areas experienced a smaller boom and bust. For example, in states with a capital requirement above $10,000, a given crop price change led to only one half as many new bank entries when compared to states with lower capital requirements.

Third, when the bust came in the early 1920s, the authors find, those banks that were more aggressive and increased their balance sheets more during the boom were more likely to fail. The increase in lending was through riskier loans that ultimately failed when crop prices dropped.

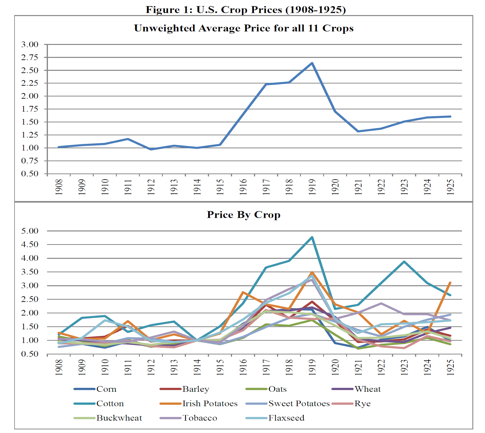

To find these results, Jaremski and Wheelock use the agricultural boom and bust — a “shock” that started outside of the financial system — and then follow the effects through time. World War I destroyed agricultural production throughout Europe, which drove up agricultural prices in the United States. Figure 1 below shows the clear boom from 1915 to 1919. Farmers and lenders expected this boom to persist. However, after the war, agricultural production in Europe recovered over just a few years and prices almost returned to their earlier level by 1921.

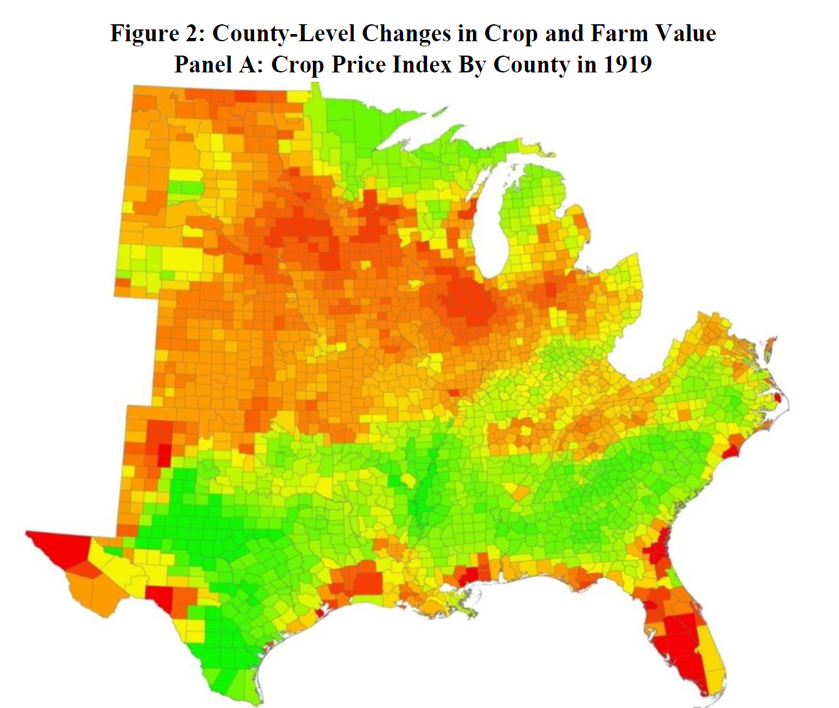

During the period, agricultural prices were not uniform across the country. As the authors note, “the South, where cotton and tobacco were dominant crops, and the upper Midwest, where buckwheat and Irish potatoes were widely grown, generally experienced larger price gains than the Midwest and Great Plains, where corn and wheat were major crops.” The geographic variation is shown in figure 2, panel A.

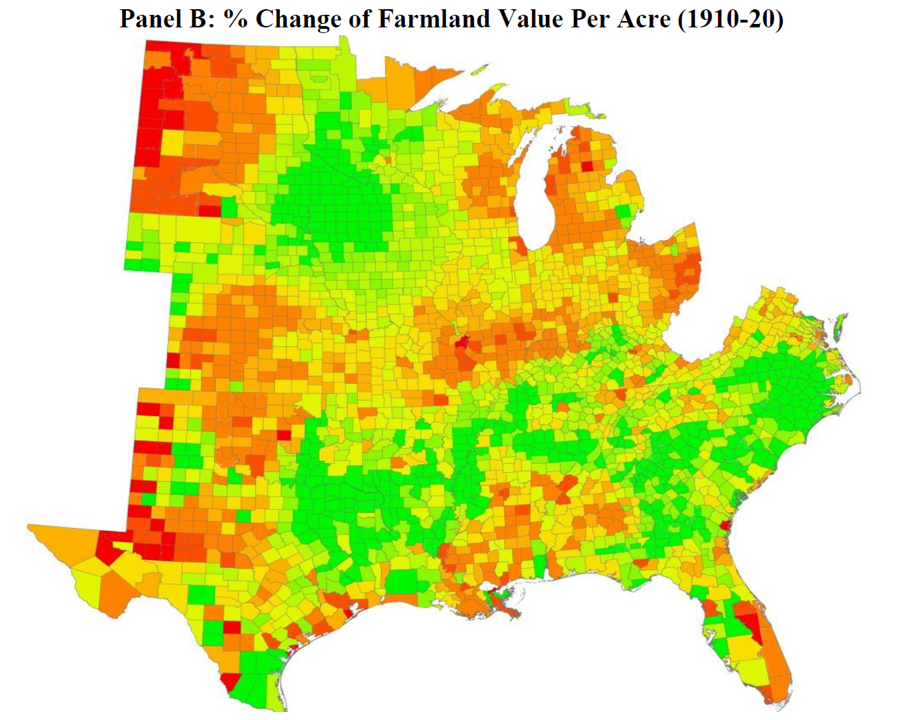

Rising crop prices drove up prices for farmland as well, although the rise was not perfectly correlated with the crop price rise. The farmland price increase is shown in panel B below.

In addition to the crop differences across regions and counties, there were differences in the banking sector because banking was local. Federal law banned interstate banking, and most states either prohibited or severely restricted any form of bank branching within a state.

The geographic variation allows the authors to identify how the general increases in agricultural prices caused by World War I interacted with the banking sector to exacerbate the boom and bust in certain regions more than in others.

While their approach does not allow us to know what would have happened if regulations were different, such as if there were no restriction on branch banking, the authors have contributed to our understanding of booms and busts when such regulations are in place. This should help inform us about how to avoid the next crisis, in a world with heavy banking regulations.