The Overnight Lending Intervention That Wasn’t

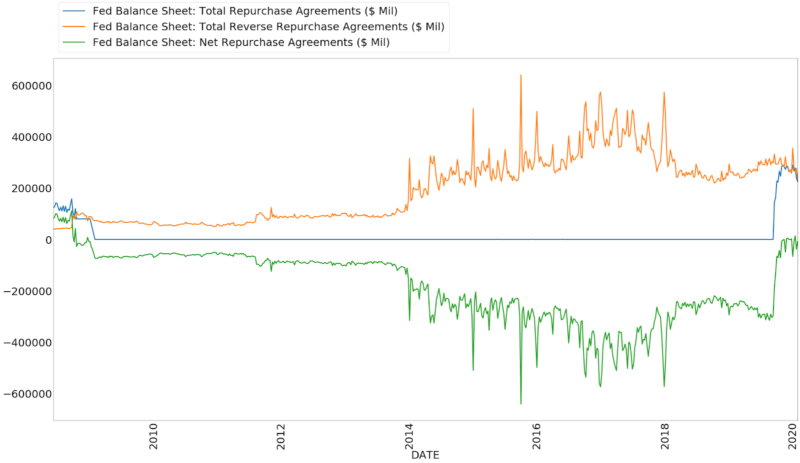

Recent intervention in the overnight lending market is not precisely an intervention. In some ways, it is a dis-intervention. Viewed in terms of the net effect of activity by the Federal Reserve, the recent accumulation of repurchase agreements has only just recently offset the contractionary effects on overnight lending exerted by its holdings of reverse repurchase agreements.

When the Federal Reserve increases its holdings of repurchase agreements, it provides a short-term loan to investors in the overnight lending market. Accumulation of reverse repurchase agreements accomplishes just the opposite. The Federal Reserve borrows from investors in the overnight lending market.

When the Federal Reserve acquires a repurchase agreement, it increases the quantity of funds in the overnight lending market. When it acquires a reverse repurchase agreement, it removes funds from the market. Accumulation of repurchase agreements by the Federal Reserve provides monetary stimulus to the overnight lending market. Accumulation of reverse repurchase agreements depresses private lending in that market.

Since the start of the crisis, the Federal Reserve’s net effect on overnight lending has been negative. I was at first surprised by this finding. The common response in the media has been that the Federal Reserve has provided significant support for overnight lending. The reality is that Fed intervention has been a millstone for the overnight lending market, having removed as much as $536.6 billion.

Since early 2009, the Federal Reserve owned only reverse repurchase agreements. The Fed’s accumulation of repurchase agreements in September was the first of its kind since that time. The overall influence of the Federal Reserve on the overnight lending market is represented as the difference between the value of its repurchase agreements and its reverse repurchase agreements. These include “overnight” agreements where the Federal Reserve purchases or sells U.S. Treasuries as part of a repurchase or reverse repurchase agreement. This value had hovered around -$250 billion for much of Powell’s tenure and only became positive in November. At present, the net effect of Federal Reserve holdings of repurchase agreements and reverse repurchase agreements is approximately zero.

U.S. Treasuries and the Fed’s Balance Sheet

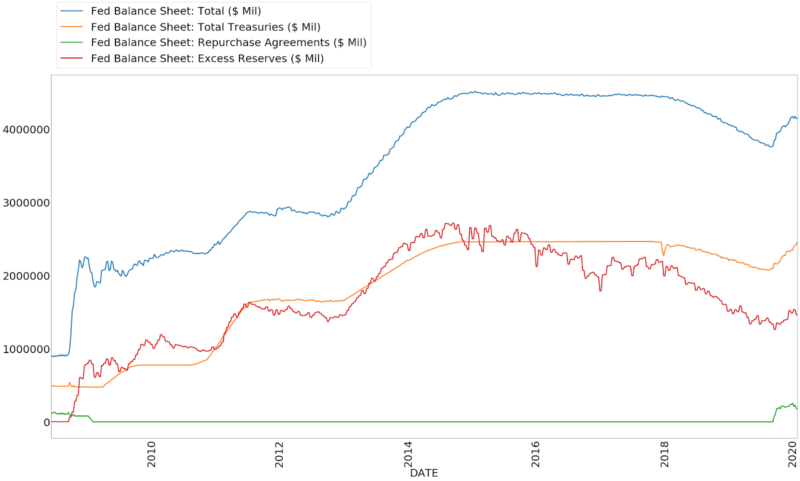

After Powell took the helm as chair in early 2018, he consistently reduced the Fed’s balance sheet. That was true until the recent intervention that began in September 2019. The initial expansion of the balance sheet that occurred in late September and into October owed largely to the increase in holdings of repurchase agreements. (In the plot, I have included overnight repurchase and reverse repurchase agreements as part of “Total Treasuries,” not as part of “Repurchase Agreements.” For “Total Treasuries,” the difference between “Overnight Repurchase Agreements” and “Overnight Reverse Repurchase Agreements” is added to “Treasuries Held Outright.”)

Since September, the Federal Reserve has consistently increased its holdings of U.S. Treasuries. This is responsible for the steady increase in the size of the balance sheet even after Fed holdings of repurchase agreements stabilized.

Interest rate volatility in the overnight lending market has provided the Federal Reserve a pretense for increased support of the Treasury market. The persistent growth of Treasury holdings by the Federal Reserve suggests this is the more significant effect of expansion. The initial volatility in the overnight lending market appears to have been the result of the maturation of U.S. Treasuries. The new offering of U.S. Treasuries pulled resources from the overnight lending market that were not offset by inflows from elsewhere.

Powell’s approach was twofold: relieve the pressure placed on the overnight market by the Federal Reserve and provide support for federal borrowing.

While Powell has simultaneously solved these interdependent problems, the move has revealed difficulties faced by the current regime. A reduction of the Fed’s balance sheet necessarily reduces support for federal borrowing. Without support, rates paid on U.S. Treasuries will rise, as will rates in other markets. This is particularly true for short-term borrowing, as we observed in September. The new intervention, however, moves the size of the balance sheet back above $4 trillion.

If Powell maintains this course, we will likely observe a sustained increase in the quantity of excess reserves held at the Federal Reserve. Since September, the path of excess reserves has begun to tick upward, suggesting that the preceding downward trend may reverse. If the Federal Reserve balance sheet continues to expand, the only way to prevent this would be for Powell to, once again, increase the discrepancy between the federal funds rate and the rate of interest paid on excess reserves. This would draw excess reserves into the market as the payoff of investments would increase relative to the rate paid on excess reserves. Powell has shown no indication that this is his intention as the rate paid on excess reserves remains 20 basis points below the federal funds rate.

There may be a silver lining in the recent changes. The Federal Reserve has somewhat decreased its level of repurchase and reverse repurchase agreements since November. This reduction has been relatively small compared to the recent expansion. Still, it would not be unreasonable for the Federal Reserve to continue reducing the value of holdings in sync with one another. This would be one means by which it can reduce the size of its balance sheet without exerting a net effect on the market.

At present, holdings of repurchase and reverse repurchase agreements have hovered from around $260 billion to $280 billion. Since these values are about equal, the Fed is essentially intermediating these funds, borrowing from and lending to investors in the overnight market. Thus, simultaneous reduction of these balances would not harm these markets.

The only reason for maintaining large balances would be for the Federal Reserve to have a means of more swiftly influencing overnight lending by asymmetrically reducing holdings of either category of instrument. Thus, it could ease conditions by reducing holdings of reverse repurchase agreements or tighten conditions by reducing holdings of repurchase agreements.

Throughout his tenure, Powell has shown a willingness to reduce the weight that the Federal Reserve places on financial markets. He was the first chair since the 2008 crisis to reduce the rate of interest paid on excess reserves relative to the federal funds rate. He has increased this discrepancy twice now. He also consistently reduced the size of the balance sheet until September 2019.

Although Powell is the chair, he faces pressure from both inside the Federal Reserve board and Congress. To implement change, he must either withstand this pressure or accomplish his goals by a means that does not generate resistance from them. The current strategy seems to take the latter approach. Time will tell if he can reduce the Fed’s footprint moving forward.