The Myth of “Neoliberal” Academic Hegemony

Almost every week news outlets such as the Chronicle of Higher Education carry new opinion essays bemoaning the decline of the humanities in the American university system. As the typical narrative goes, fields of study such as English, history, foreign language, and philosophy are under assault from a “neoliberal” takeover of higher ed that gives preference to the skills-oriented STEM disciplines and “devalues” everything else.

The fruits of this alleged devaluation appear in the humanities’ notoriously weak academic job market as well as the shedding of majors over the last decade. Together, these patterns supposedly reveal a society that has turned its back on the concept of a well-rounded liberal education. The results of this disinvestment, we are assured, will manifest in the coming decades through severe societal repercussions such as the loss of cultural imagination and a decline in critical thinking skills, even among formally educated persons. Unless we reverse course and recommit ourselves to investing in the humanities again, these patterns will inflict us with a society-wide cultural malaise from which we may never recover.

Or so the story goes.

Yet as Jason Brennan and I document in our new book, Cracks in the Ivory Tower, the conventional narrative of an assault on the humanities is unsupported in evidence.

To be clear, the number of majors in these fields is on the decline, and academic employment in the humanities currently faces a glut of applicants. But these are actually symptoms of a very different problem — one that stems from decades of overinvestment in the creation of humanities PhDs combined with ignoring basic signals about what students want to study.

The Myth of the Disappearing Humanities

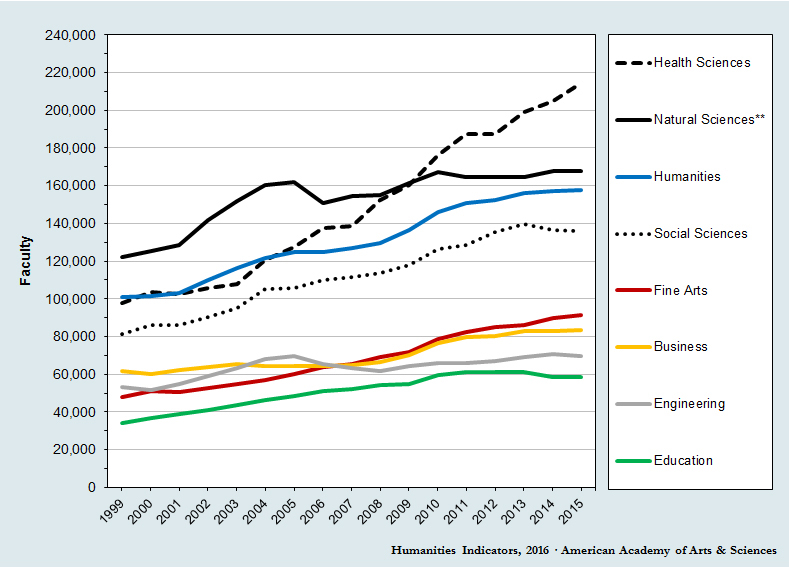

Contrary to conventional wisdom, academic jobs in the humanities have not dried up. In fact, the total number of humanities professors has grown at a faster pace in recent decades than most other areas of the university system. Between 1999 and 2015, academic employment in the humanities actually grew from about 100,000 to just shy of 160,000 faculty — a bigger numerical gain than every other field with the exception of pre-professional programs in health care.

Furthermore, job growth within the humanities kept pace with the expansion of the university system as a whole even as many other disciplines did not. Job growth in the physical sciences actually stagnated somewhat in this same period, leading to a modest decline in their overall share of the faculty despite being part of the much-discussed STEM emphasis.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Occupational Employment Survey

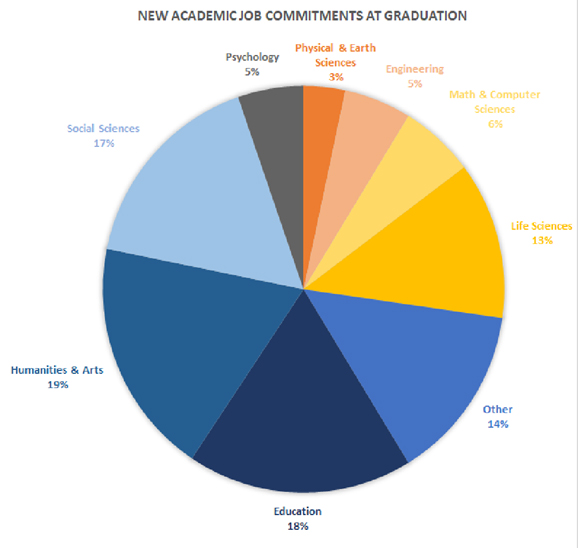

Similar gains may be seen in annual statistics on academic hiring as tracked by the Survey of Earned Doctorates. The chart below depicts the percentages of newly minted PhDs with an academic job offer at the time of graduation for 2015, the most recent year available. That year, the category of “humanities and arts” claimed about 19 percent of the roughly 7,300 newly hired professors in the United States, making it the largest single category.

Source: Academic Job Commitments at Graduation (2015 hiring cycle), Survey of Earned Doctorates

And yet, despite clear job growth and despite capturing the lion’s share of new faculty positions, the humanities still have the worst job-placement record in academia. So what is actually going on?

The answer is not the “devaluation” of the humanities, but rather the rampant overproduction of humanities PhDs relative to the number of new jobs being created. In the same year that the humanities placed almost 1,400 new faculty jobs, they also issued over 5,800 new PhDs — the largest total on record.

Not all of these new PhDs attempted to secure academic employment, and many go on to work in the private sector or government. But the pattern is clear: humanities job opportunities in the academy are growing, but the number of new applicants is growing even faster.

The Humanities PhD Glut

Ironically, the sources of this glut stem from a related problem: decades of overinvestment in humanities PhD programs, many of them at weaker schools with little track record of placing their PhDs in academic jobs.

This finding runs directly against the popular narrative, but it appears clearly in evidence. Using annual graduation statistics, we found that the total number of actively operational PhD programs in English, history, and foreign languages (the three largest humanities) all grew between 2006 and 2015. The reason appears to derive from the incentives of how academic departments operate.

Having a PhD program in one’s own department is a substantial job perk for university professors. It conveys prestige to their peers at other universities. It usually translates into more funding for the department, which means an ability to hire more faculty. It also supplies faculty with a stable stream of teaching assistants to do their grading and research assistants to help with their own projects, all pulled from the current crop of PhDs-in-training. Due to faculty pressures to retain and expand these perks of having a doctoral program, universities seldom cull their PhD offerings except in the rare case of a complete collapse in enrollment. Instead, they overinvest in new PhD production — even from low-ranked programs with few PhD placements to their credit after graduation.

This overinvestment in PhD production, in turn, creates a perpetually glutted academic job market that far outpaces new faculty hiring, even when the latter is also increasing faster than most other areas of the university system.

The Decline of Humanities Majors

At the same time new humanities-PhD production is booming, the number of undergraduates who choose to major in these same subjects is in a state of free fall. The annual numbers of bachelor’s degrees in English, history, and philosophy have all taken a hit as student interest shifts to other subjects.

The reasons behind this shift are complex and multifaceted. Some point to weak external employment opportunities for these majors in the private sector, although increasingly a bachelor’s degree — any bachelor’s degree — will work as a signaling credential in an entry-level job that otherwise does not require a trade-specific skill set.

Other, less examined explanations include changes in the content being offered by the humanities. University campuses have become hyper-politicized in the last 15 to 20 years, with a historically unprecedented skew toward the Far Left emerging among the ranks of the professoriate.

Survey data consistently rank the humanities among the most politically biased disciplines. Neither the general population nor incoming undergraduates have followed the professoriate’s leftward shift in political self-identification. It’s therefore possible that students are simply voting with their feet and steering clear of majors that only cater to left-wing political activism.

It may also simply be the case that humanities departments no longer invest the necessary efforts to recruit majors – a complacency that may derive from tenured faculty spending less time on instruction, and departments assigning more core classes to part-time adjuncts.

Learning the Gen Ed Hustle

Another factor, however, may hold the key to both the decline of undergrad humanities majors and the growth of the humanities’ presence on campus. Over the past 30 years, universities have undergone a measurable curricular shift toward “general education” classes, or mandatory course offerings in specific subjects that all students must take and pay for as a requirement of graduation.

Gen edss have always been a part of academia. Most schools require a certain number of history credits, math credits, science credits, fine arts credits, and so forth as part of a “well-rounded” curriculum, even if the student is majoring in a completely unrelated field.

But gen ed requirements have become more stringent over the years, and tend to concentrate heavily in the humanities. A single semester of writing composition may have been the norm 30 years ago, whereas today it is common for universities to require two or three semesters. Similar patterns may be seen in foreign-language requirements. Many campuses have also added a sequence of required courses under the label of “First Year Experience” — usually a humanities or social science–centric “introduction” to university life, as taught by humanities departments.

My coauthor Jason Brennan explains the reasons for the growth of gen eds in a short article summarizing our findings. Quite simply, gen eds are an effective way for faculty in unpopular majors to force students into their classrooms, and more students in seats translates into more funding and job security for the beneficiary department. Professors often cloak these requirements in appeals to lofty rhetoric about making their students “well-rounded” and culturally literate, but decades of empirical data strongly suggest that most students do not actually learn anything in these classes. They are, however, a effective way to ensure funding for your own department.

As the popularity of humanities majors drops, gen ed requirements in the humanities take their place as a way of filling classrooms. And since gen eds are both mandatory and growing in frequency, they in turn provide their own justification for hiring even-larger numbers of faculty to teach the same disciplines. The result is the clear growth in humanities-faculty hiring that we see in the data above, even as undergrad majors decline.

So, far from being a perpetually beleaguered sector of the academy facing devaluation and budget cuts, the humanities have actually become an entrenched and growing feature of academic life. Unlike disciplines that must recruit their own majors through the classroom, the humanities have a guaranteed audience of students through mandatory gen ed classes — and with it a vast and growing faculty footprint on campus.