The monetary ripples of Brexit

June 23 will most likely be remembered as a turning point in Britain’s fate, as 17.4 million Britons expressed their desire to sever ties with the European Union (EU) in a historic referendum. The British, and global, economy is facing an imminent cloud of uncertainty. From the moment that the markets opened, and crashed, last June 24, the whole world wondered, “What will Britain do next?”

Unfortunately for the world, the right question might be, “What will the Bank of England do next?”

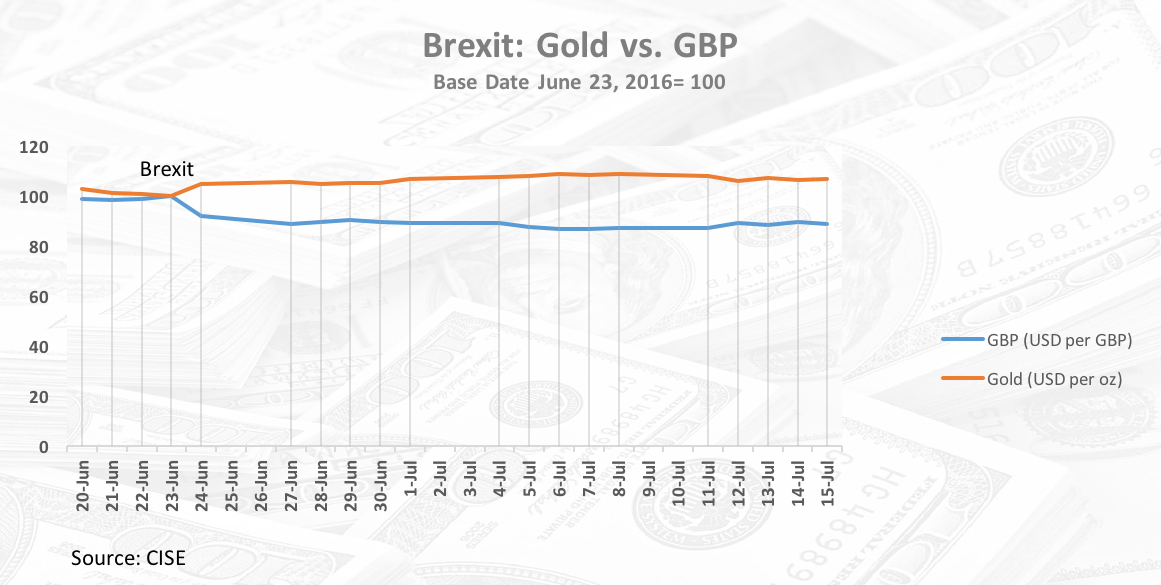

Article 50, the trigger that will enable Britain to leave the bloc, has not been pulled yet and for some time the UK will remain a full EU member. However, markets are already reacting and analysts forecast a “material slowing” of economic growth as a result of the referendum. Uncertainty was high, but is now even worse. The pound fell to its lowest level since the mid-1980s, losing over 10% in a matter of minutes. The euro also fell by 2.6% against the dollar. In this context, investors decided to flee from the pound and safeguard their investments in assets such as gold or the debt market.For this reason, on July 6 gold reached its highest price in the last two years, trading for more than $1365 per ounce, thus soaring by 28% so far this year. However, some experts estimate that it could reach upwards of $1400. Likewise, this rally is also impacting the yen, which achieved a 5% appreciation against the dollar.

As mentioned above, the other side of the coin is the debt market. Since Brexit, US bond yields have reached historic lows. Similarly, Spanish yields are also at their lowest level since March 2015, now at 1.15%, and German bond yields are also at a record low of -0.177%. Needless to say, Japanese markets have not faired better.

Apart from that, yet another consequence of the Brexit vote is that the Federal Open Market Committee’s expected rate hike is expected to be delayed yet again, with investors even betting that they will remain stable until 2017.

Likewise, the ripple effect of the British referendum extended to Asia where central bankers are now preparing to ease their monetary policies. Uncertainty hits trade reliant economies especially hard as it tends to cause a wider downshift in trade and investment. When investors don’t know what to expect, time and resources are misallocated and losses are suffered.

But of course, one should not be surprised that in the light of such uncertainty, central bankers are quick to come to the rescue—with discretion, of course. As Dr. Judy Shelton notes, “One would have expected global leaders to call into question existing international monetary arrangements — not only to prevent another debilitating disconnect between credit flows and real economic activity, but also to establish an orderly and stable foundation for global economic growth. Instead, we see a continued reliance on the acumen of central bankers to avert economic disaster through monetary activism — despite the track record of those who wielded total discretionary authority.”

These days, when things get bad, it’s fair to assume that central bankers will make them worse. With Brexit still in the works, that’s a scary thought.

But at this juncture, what monetary policy strategy will the Bank of England pursue?

While experts expected a cut of 25 basis points in the interest rate by the Monetary Policy Committee, the Bank of England backed away from an immediate monetary stimulus last Thursday. In addition, it decided to continue with the quantitative easing program which was introduced in 2009.

According to statements by Mark Carney, Governor of the Bank of England, “The economic outlook has deteriorated and some monetary policy easing will probably be required over the summer.” However, it should be noted in mind that interest rates are already low and have been for seven years. If the government insists on cutting interest rates or restarting quantitative easing, it could lead businesses and consumers to conclude that the situation is worse than it actually is and trigger the loss of confidence that the BoE is trying to avoid. Signals matter.

Of course the BoE’s willingness to engage in still more quantitative easing is regrettable, although hardly surprising. As Stephen Williamson stated in a 2015 St. Louis Fed paper, “There is no work, to my knowledge, that establishes a link from QE to… inflation and real economic activity. Indeed, casual evidence suggests that QE has been ineffective.” Yet even if there were evidence that would suggest that QE had positive effects, the Bank of England’s report The Distributional Effects of Asset Purchases notes that, “The benefits of loose monetary policy have not been shared equally across all individuals. Some individuals are likely to have been adversely affected by the direct effects of QE.” The paper concludes that, really, QE only benefits the top five percent of society, and has little real effect on the economy.

The Brexit vote brought about a great deal of volatility and is driving central banks further into the depths of monetary activism. Regardless of the monetary path chosen, however, the biggest long-term risk seems to be political. Unfortunately for us, that term now encompasses central banks and their tireless discretion that could ultimately encourage protectionism and reverse the benefits of our globalized economy.

Yamila Feccia is an economist at Fundación Libertad in Argentina.