The Fiscal Centralization of Europe Will Not End Well

One of the side effects of the corona pandemic has been a new, integrated fiscal response from European governments. After five days of negotiation (estimated by some commentators to be the longest in EU history) the EU27 agreed, last month, to allow the raising of debt at the federal level. The amount is a mere Eur750bln but the action marks the beginning of a new phase in the European experiment.

The new Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF), as the EU budget deal is known, will cover seven years between 2021 and 2027. The deal has two parts, the regular EU budget, worth nearly Eur1.1trln and a Eur750bln Next Generation fund – or NGEU. It is worth noting that, in a departure from previous policy, Eur390bln will take the form of grants. Not only will this not add directly to European governments’ debt loads, but it breaches what had always been deemed to be a red line in allowing intra-EU fiscal transfers.

The ‘exceptional and temporary’ nature of the NGEU has gone some way towards appeasing the ‘Frugal Four;’ Austria, Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden. On closer inspection, however, they appear to have been incentivised rather than undergoing a damascene conversion. The principal inducement has been the award of substantial budget rebates as part of the final settlement. Nonetheless, commentators are already heralding this brave new federal solution as a template for dealing with future crises.

The new federal era has not quite got underway, and there remain a number of technical issues which need to be addressed. The new debt will not be guaranteed by member states, which immediately raises the question of how the borrowing will be repaid. Individual governments, frugal or otherwise, have long resisted calls for the European Commission to be granted tax-raising capabilities, and, more importantly, investors will need to be confident, not just of the return on their investment, but the return of their investment, if they are to be relied upon to finance these new federal obligations.

The largest beneficiaries of the NGEU funds are likely to be those hardest hit by the effects of the pandemic, namely Italy and Spain. There have been noticeably few strings attached to the loans. Labour and pension reforms, which are critical for future fiscal rectitude, but politically unpalatable, have formed no part of the deal. The allocation of new funds will, however, be subject to an ‘emergency brake’ should any EU member object to the spending proposals of any other. This is likely to encumber the disbursement process.

Despite the very different origin of the EU, it has been suggested that this is its ‘Hamiltonian moment.’ In the aftermath of the Revolutionary War in 1790, Alexander Hamilton, the first US Secretary of the Treasury, solved the debt troubles of the Northern states (and enraged many in the South) by introducing federal debt which would be covered by means of federal taxation. The Southern states (much like the Frugal Four) extracted considerable concessions. This may seem similar to the current situation confronting the EU but Johannes Hahn, European Commissioner for Budget and Administration, has been at pains to insist that it is not.

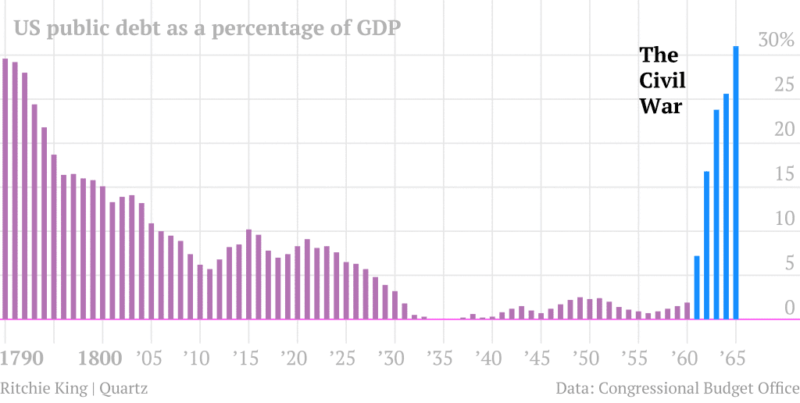

Setting aside the ‘exceptional and temporary’ nature of the current situation, there is a major difference between the US of the late 18th and 19th century and the EU today. Between 1790 and 1849 the federal budget was mostly in surplus – this being achieved through a mix of fiscally conservative policies. A second and current difference to consider is that, in the US today, the ratio of public spending to GDP is around 35%, whilst in Europe it is already 45%.

The chart below is a testament to the fiscal conservatism of the early United States. It shows the declining ratio of US debt to GDP after 1790. The reversal only occurred with the outbreak of the Civil War in April 1861: –

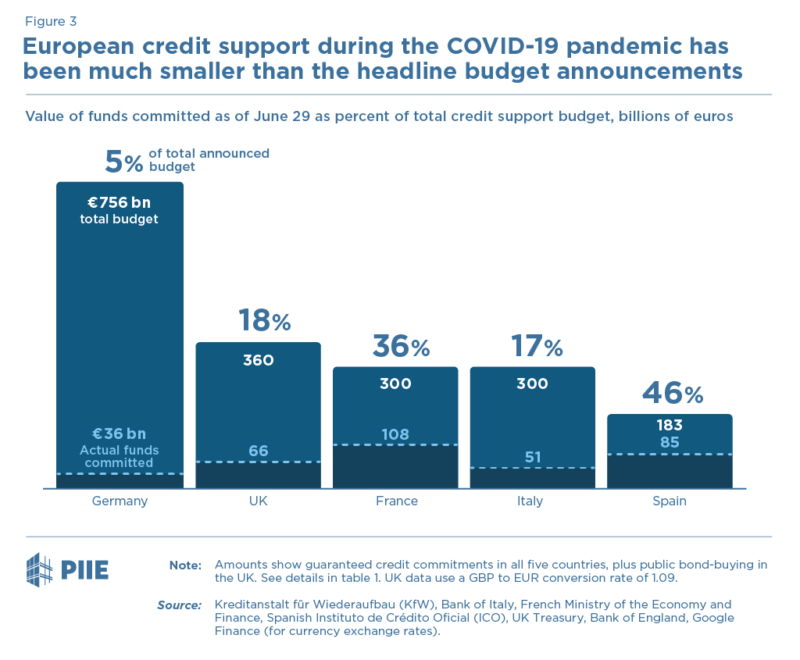

Returning to the present, calls for EU debt issuance have been growing for several decades, but was this the right time for a coordinated federal EU response? A recent study by the Peterson Institute found that only a small proportion of the individual state commitments which were made in response to the pandemic have so far been disbursed: –

On the basis of the chart above it might be argued that the issuance of ‘Euro Bonds’ is surplus to requirement, an opportunist manoeuvre on the part of federalists. However, a counter argument can be made for the use of such instruments to show consensus in the face of adversity. In the aftermath of the Great Financial Crisis the US decision to implement its Troubled Asset Relief Program, which assumed many of the nonperforming loans of the US banking system, allowed the US economy to rebound far more quickly than that of Europe. The Europeans do not want to repeat the mistake of not acting in haste; however, they may be afforded the privilege of repenting at leisure for many decades to come.

Market Response

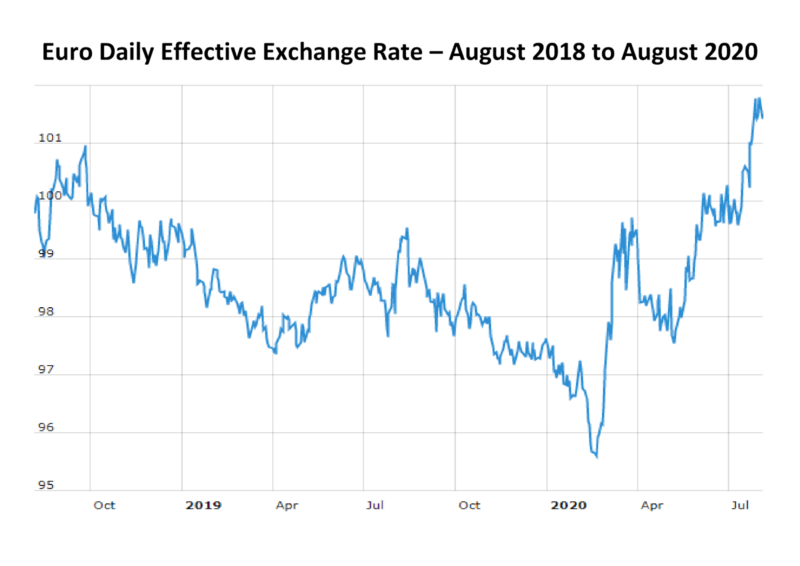

To judge by the direction of the Euro, financial markets view the issuance of Euro Bonds favourably. The chart below shows the Euro daily Effective Exchange Rate over the last two years: –

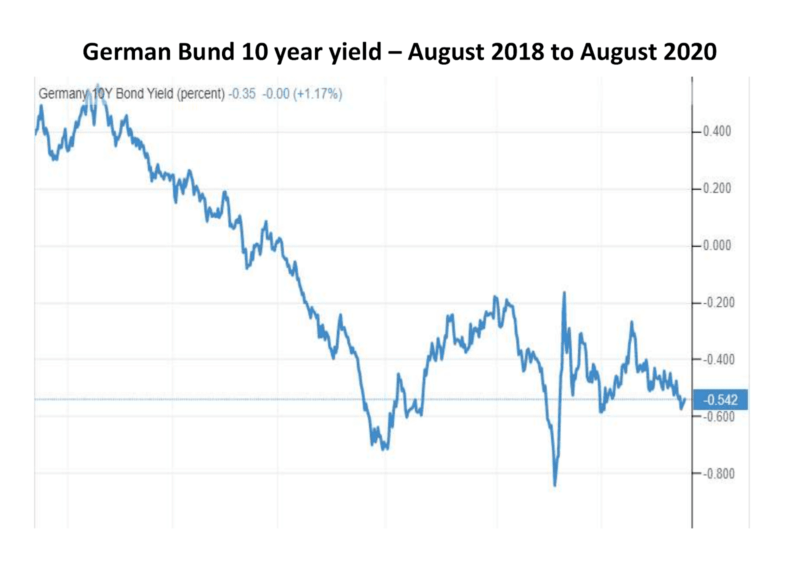

The German 10yr Bund has also taken the dilution of Germany’s fiscal authority in its stride. After an initial ‘flight to quality,’ in February, which saw a new record negative yield, at the commencement of the pandemic, German yields backed up to -0.18% as the enormity of the economic cost of COVID began to dawn on financial markets participants. Then came the first wave of coordinated stimulus, during which yields became more negative once more. This was followed by a further period of reflection about the strength of EU resolve. National borders closed and yields rose. One of the EU’s five freedoms, free movement of people, was being called into question. Suddenly it seemed as if nationalist interests might challenge the very essence of the European project.

The federalists prevailed and since the five-day debate German Bund yields have tumbled once more, despite the fact that Germany is likely to foot the lion’s share of the cost of the new federal debt: –

Beyond the exceptional and temporary

Assuming that the issuance of EU-backed debt will be neither exceptional nor temporary, there are a number of structural concerns which need to be addressed. To begin with, there has been no indication of either the expected or desired federal deficit which might be undertaken. In addition, the cost of borrowing has yet to be clarified.

The means by which the debt will be repaid remains hypothetical. It is proposed that taxes be raised from member states, but it is unclear from whom these taxes will be extracted. The issuance of a Euro Bond is also assumed to be the harbinger of EU-wide federal taxation, but in order to push this cathartic change through a reluctant European Parliament, the Commission proposes to commence federal taxation with a series of populist taxes, starting with an additional tax on digital technology companies.

The estimated income from this tax is put at Eur10 bln, a doubling of the initial estimate when a European digital tax was first proposed. There will also be a tax grab focussed on the 70,000 companies, both domestic and foreign, with annual revenues exceeding Eur750 mln/annum – for international companies this will essentially be the ‘price for access’ to the single market.

Finally, in order to win the ‘Green’ vote, the Commission suggests the imposition of further environmental taxes. At no point are spending cuts considered, no research is proffered to support the tax revenue estimates and the economic impact assessments, which usually accompany Commission proposals, are notably absent. It seems these are exceptional circumstances and demand nothing less than exceptional hyperbole.

Conclusion

This next stage of the federalisation of Europe is only just beginning. To judge by the initial reaction of the financial markets, there is hope that we are not on an accelerated ‘Road to Serfdom.’ However, as we saw in the 2011 Eurozone crisis, financial markets can be fickle friends. For the present, a global fiscal and monetary response to the pandemic has convinced investors that the prospects for European debt have improved. There will inevitably be further Euro Bond issuance together with more careful scrutiny of the means by which revenues can be raised to pay interest and repay principal.

When Arthur Laffer showed, graphically, the relationship between the rate of taxation and tax revenue (which assumes an optimal tax rate above which tax revenues decline) he was describing a phenomenon which had been observed since the Middle Ages. The Commission needs to carry out a careful economic impact assessment, sooner rather than later, if they hope to avoid a loss of confidence in their ability to meet their new debt obligations.

Europe may be experiencing a ‘Hamiltonian moment,’ but the path towards a federal Europe will remain both long and tortuous. Political opposition to the European experiment has been growing as the perceived costs of membership of the EU begins to eclipse the benefits for some members of the Union.

In Brussels, the will to unite is still strong but elsewhere in the Union there are signs of rising dissent. As a cautionary final thought for European bond investors, Euro Bonds may end up being used to federalise the outstanding debt of all EU member states, but at high cost to those countries whose debts are most manageable.