The Case For 100% Reserve Banking

by Devin Roundtree

Even among the most vocal advocates of returning to a gold standard, a banking system that requires banks to reserve 100% of all deposits redeemable on demand is considered impractical and a hindrance to economic growth. However, not only is 100% reserve banking practical, it is lawful and will not create credit bubble induced business cycles.

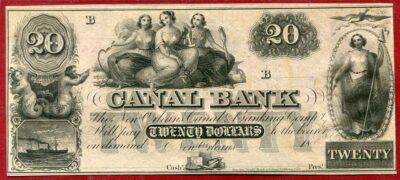

This banknote issued by the Canal Bank during the 1830s reads, “The New Orleans Canal and Banking Company will pay Twenty Dollars to the bearer on demand.”

The Legal Case

During the 19th century, people paid a small fee for the safety and convenience of storing their gold and silver at a bank. Depositors could choose from two types of money substitutes: an open checking account redeemable on demand or a transferrable receipt that gave the bearer the right to redeem the money on demand (see picture). Of course the only way banks could uphold their contract to redeem on demand was to reserve 100% of all demand deposits. However, when banks received new deposits, they reserved just a fraction and issued a loan to a business on the residual. In doing so, banks created multiple claims for the same money. For example, if someone deposited $1,000 in gold coins at the Canal Bank, the bank would only reserve a fraction, let’s say 40%, and loan out $600 in money substitutes. As a result, the bank created $1,600 in money substitutes redeemable on demand, even though only $1,000 in gold coins existed. Whenever more money substitutes were redeemed than banks had money on reserve, a bank run would ignite. Thanks to the government, the Federal Reserve Note (redeemable only for more of the same) has become money itself, but the unstable practice of fractional reserve banking continues with checking accounts.

Bankers have always argued that based on the habits of depositors, a bank need only keep “adequate” reserves to meet their contractual agreements. If more money substitutes are redeemed than expected, then the bank has simply made an error. This is analogous to someone who gets caught running a Ponzi scheme and tells the police that he simply underestimated how many investors would call to liquidate their investments; or an embezzling accountant who takes the day’s take down to the casino and tells the police that he simply shouldn’t have hit on 16. It matters not that banks only promise to redeem on demand, instead of guaranteeing to do so. Banks knowingly violate their contractual agreements to redeem on demand the second they loan out un-backed notes designed to be indistinguishable from those that are truly backed. Just like the Ponzi scheme, banks are betting that most of their depositors won’t come to redeem their money. In a free market, fractional reserve banking would be treated no differently than any other act of theft or fraud.

[So long as the accounts are not labeled as “demand” accounts, and all recipients of the notes are made to understand the conditions, maintaining a fractional reserve system is not inherently fraudulent. This, however, has not traditionally been the case with fractional reserve institutions which have instead sought to portray their notes as “good as gold” and fully backed, and then resorted to government intervention to prevent the inevitable result of such deception. Under a free market system banks would be allowed to issue any notes they chose, subject to honest practices and full disclosure, and people would be free to accept or not accept, or discount notes appropriately that could only be withdrawn conditionally or were backed by only a fraction of their nominal value. The key is that note issuers would be legally mandated to reveal their reserve ratios if they claimed that their notes were backed by any commodity. –ed.]

The Practical Case

If banks have to operate on 100% reserves, banking services will not cease to exist. Banknotes, checking accounts, and check cards will still be available. Free checking accounts will likely become a thing of the past (or has this already happened?), but this should not be seen as a disadvantage for depositors. Free checking is anything but free for depositors. Most banks can only afford to offer such a service because they are loaning out their customer’s money at interest. Because fractional reserves artificially increase the supply of money substitutes, prices are higher than otherwise. So depositors may not pay for their checking accounts at the bank, but they do so at the pump and in the grocery store.

If banks want to make a profit by issuing loans and charging interest, they must first raise loanable funds by offering saving accounts, time deposits, or other interest bearing accounts. If banks want to offer customers an account that pays interest and allows for frequent debits, they can do so through savings accounts and time deposits. In order for this to work, savers would have to either maintain a certain amount of savings at all times, or be limited to a portion of savings that can be withdrawn on demand. Savers would still be able to use check cards just like a typical checking account. Practicality will not be an issue as long as banks maintain reserves equal to the amount of all deposits that can be contractually withdrawn on demand. If anything is impractical, it is the fractional reserve banking system that has produced one financial collapse after another, wasted scarce resources, and created periods of high unemployment.

The Economic Case

Under a 100% reserve banking system, business cycles will be greatly reduced, as businesses will not be universally misled by unsustainable low interest rates made possible by fractional reserve banking. Such low interest rates encourage businesses to borrow more and to expand production, but these production starts are not backed by real savings. Inevitably, interest rates rise unexpectedly (as in the home loan market, especially in Adjustable Rate Mortgages, setting off the current crisis), credit contracts, and a recession follows. It would be naïve to assume that no bank will commit fraud again. But few bankers would engage in such behavior with the consequence of imprisonment. Thus, the impact on interest rates and the overall economy would be negligible.

Given the growing disconcertion of the U.S. Dollar and the massive accumulation of gold by central banks around the world, there should be little doubt that gold and silver will reemerge as legal money. While the Classical Gold Standard that existed from 1815-1914 was far better than its successors, not every aspect should be duplicated. This was an era of regulated banking that allowed banks to operate on fractional reserves of gold and silver on demand deposits. There is a reason the Federal Reserve exists. As long as there is fractional reserve banking a centralized lender of last resort will be called upon.

Devin Roundtree received his M.A. in economics from the University of Detroit Mercy.