Taxes Haven’t Changed Much, But Spending Has

When issues of taxes and government budget are discussed, we sometimes hear of the “good old days” when top marginal tax rates and corporate tax rates were much higher.

Back then, the federal government was able to fund everything we wanted to fund, like investment in infrastructure and in science and education. Those “good old days” usually reside somewhere in the 1950’s and 1960’s. And today we don’t seem to be able to “fund everything we want to fund.”

This view implicitly assumes that the federal government used to collect a lot more money in taxes, presumably due to higher tax rates. And if we could just manage to collect more in taxes today, we would be able to fund all those wonderful programs, too.

But the reason for the more restrained fiscal circumstances today is not that we collect less money in taxes than we did in the 1960’s.

In 2014, the federal government collected 17.5 percent of GDP in tax revenues. Throughout the 1960’s, the federal government collected, on average, 17.3 percent of GDP in taxes. While this value fluctuated, it did so in a fairly narrow band. Thus, today, we collect about the same amount in taxes, relative to the size of the economy, as we did in the 1960’s.

What did change dramatically since the 1960’s is the composition of federal spending, and it is this change in composition that restrains the fiscal options today.

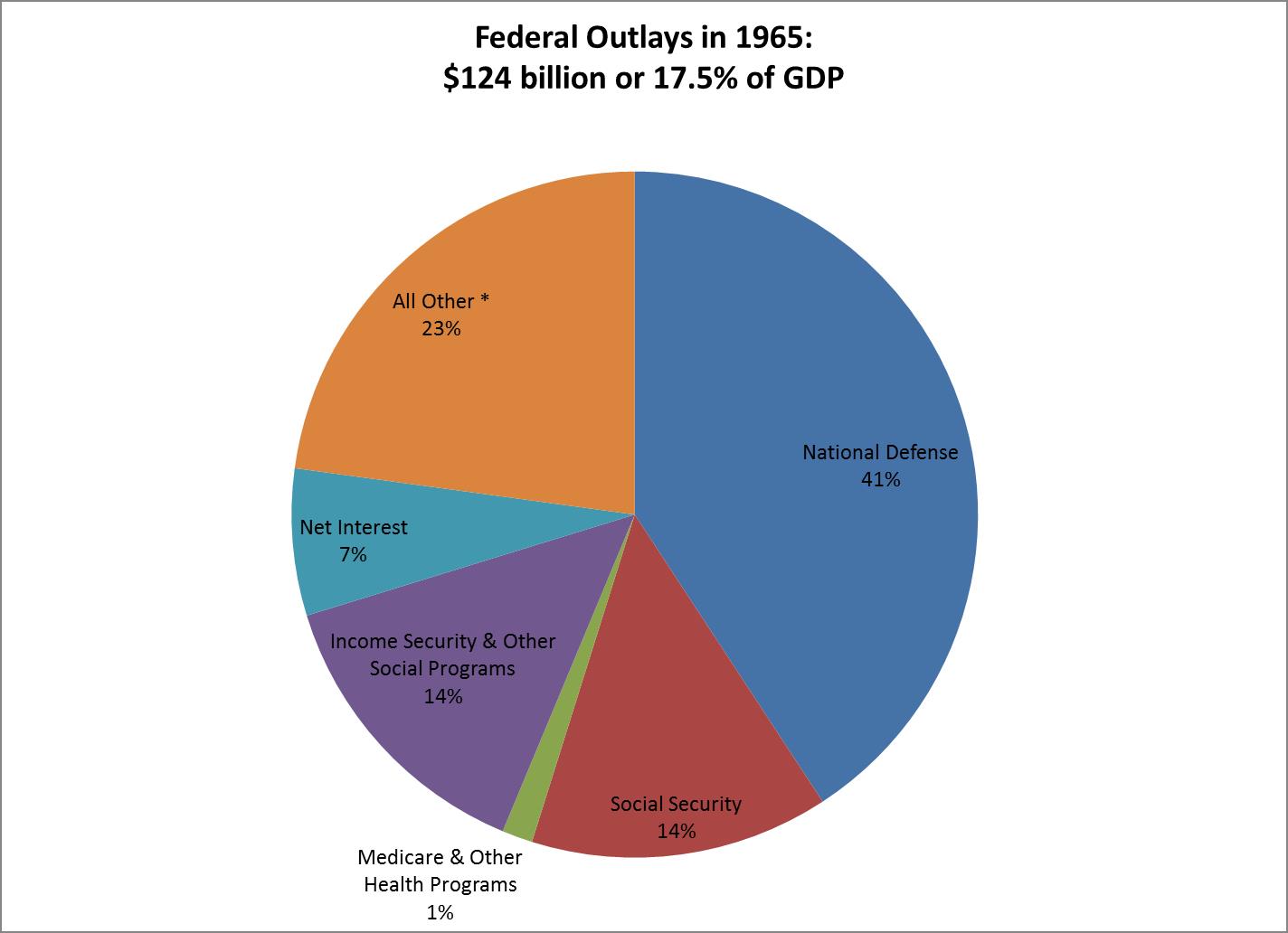

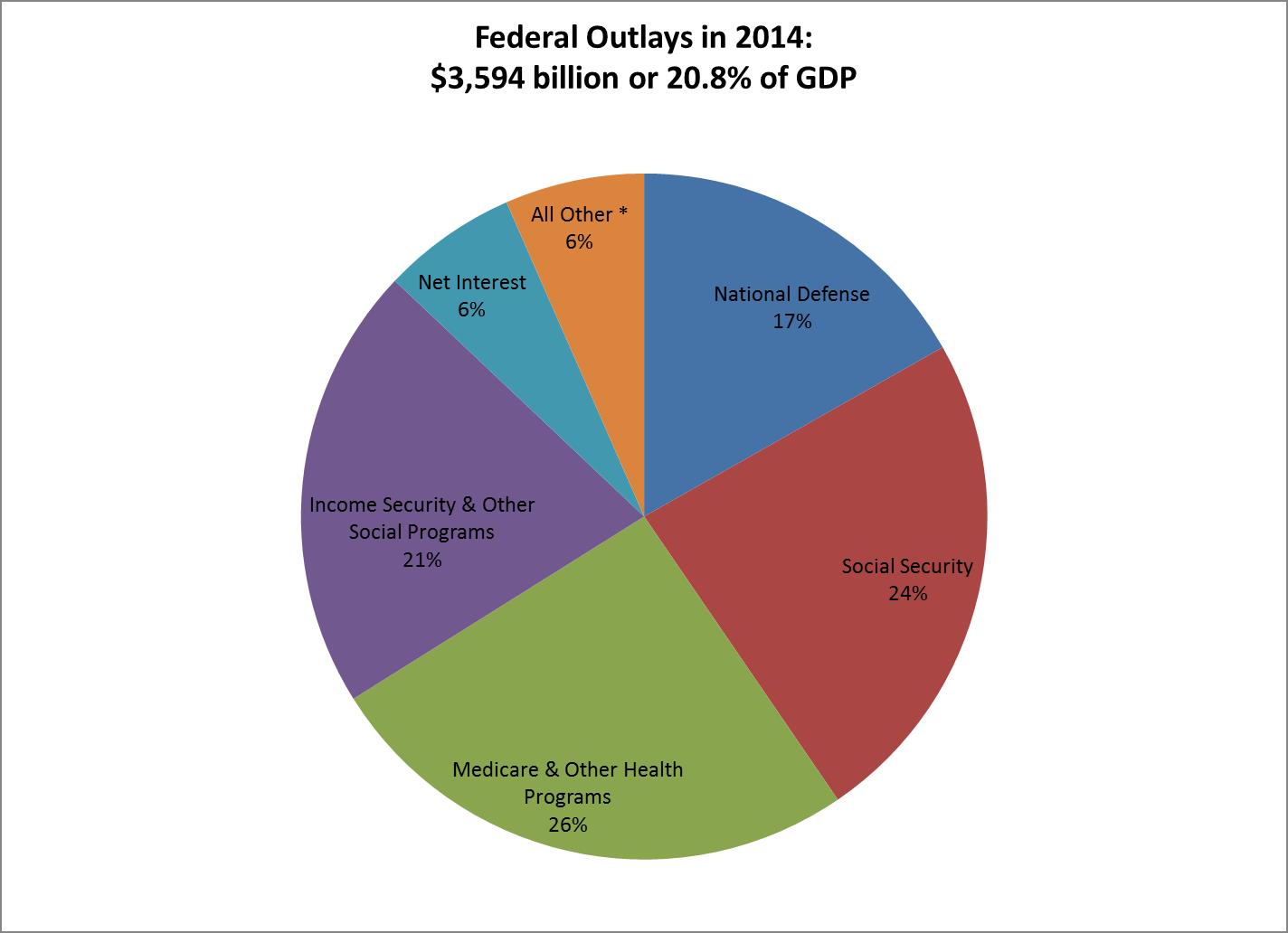

Below we compare the composition of the federal outlays in 2014 (the latest year for which we have data) and 1965 (the year Medicare was introduced; comparison to a year earlier than 1965 would take us to an even more different era, when there were no major federal health programs).

* includes investment in infrastructure, community & regional development, science & technology, administration of justice, international affairs, etc.

Source: Office of Management and Budget

Judging by the composition of federal spending, in 1965, the federal government was mostly providing national defense and investing in infrastructure, community & regional development, science & technology, and the like – about 64 percent of federal outlays went for these purposes. The government was also providing some social insurance, and was paying interest on the debt still outstanding from WWII.

By 2014, judging by the composition of the spending, the federal government was mostly focused on proving social insurance – more than 70 percent of outlays go toward various social insurance programs (Social Security, Medicare, income security, other health programs, etc.).

Federal spending on the social insurance programs constitutes what is called mandatory outlays. These outlays are preset by the legislation that governs the social insurance programs and they are not subject to the annual appropriations process.

The fact that more than two-thirds of the federal outlays go to mandatory programs means that most of the money the government collects in taxes is spoken for right away – it goes to cover mandatory outlays. As a result, “everything else we want to fund” (like education, infrastructure, research, environmental protection, disaster relief — anything that goes in that “all other” slice of the pie) accounts for a much smaller portion of the federal spending than was the case in 1965.

This is a dramatic change in the composition of outlays. Today the government essentially performs different functions than it did 50 years ago. It is not that we collect less in taxes. Rather, it is that we spend most of the money collected on things that did not even exist in 1965, leaving much less for all the other things we were so successful in funding back in the 1960s.