How Powell can Set Right Monetary Policy and Financial Markets

Much drama has surrounded the Federal Reserve chairman Jerome Powell in recent months. Some leading indicators may be signalling a coming recession. In particular, a deepening inversion of the yield curve is cause for concern. Pressure is mounting from President Trump for Powell to lower interest rates, even after many consecutive quarters of an increasing rate of economic growth.

There is some irony in the economic misunderstanding that seems to underlie a call for a decrease in interest rates. Interest rates contain multiple components. The rate of a bond is affected by the liquidity of that bond, expectation of risk that could adversely affect repayment, expectation of inflation, and the opportunity cost represented by competing investments. Under normal conditions, the last two factors dominate observed interest rates. All else equal, interest rates rise if the expectation of economic growth among investors improves or their expectation of the rate of inflation increases.

Real Income Growth and Interest Rates

The relationship between economic growth and interest rates is counterintuitive. Since inflation is associated with easy money, and easy money is associated with a lowering of interest rates that enable a greater level of borrowing, one might be misled to think that lower interest rates are a sign of easy money. After all, the Federal Reserve pegged the overnight lending rate near 0% for 7 years in an effort to promote economic recovery and sustain growth.

Ergo, rising rates must work against economic expansion.

The problem with this logic is that it reasons from a price change, treating it as a causal factor. Prices are a result of market processes. The interest rate may rise or fall for a variety of reasons. The interest rate serves as a proximate indicator of economic growth. Not coincidentally, the annual rate of growth of real GDP has been at 3 percent or greater for the last year, a sign that investment opportunities have been improving. As a result, businesses that drive this growth must compete for a limited pool of savings, bidding up interest rates in the process. This process ensures that resources are employed toward their most productive uses.

If the Federal Reserve prevents interest rates from rising as economic growth persists, it will divert resources toward relatively unproductive uses that provide relatively low rates of returns. These may seem profitable due to the lower interest rate, but the resources are malinvested. Their present employment toward lower yielding investment diminishes their ability to be used in higher yielding investments in future periods. In other words, if economic growth has promoted an increase in interest rates, to fight this increase by lowering the rate of interest may diminish economic growth in the future.

Inflation and Interest Rates

The relationship between easy money and interest rates is complicated by the inclusion of the inflation rate. Intuitively, one may expect that lower interest rates indicate easy money by the central bank. However, this discounts investor expectations. If the central bank is employing an easy money policy, they will demand compensation for devaluation of money implied by inflation. This tendency limits the ability of the central bank to distort the structure of investment by inflation alone compared to distortion that results from an attempt to set interest rates.

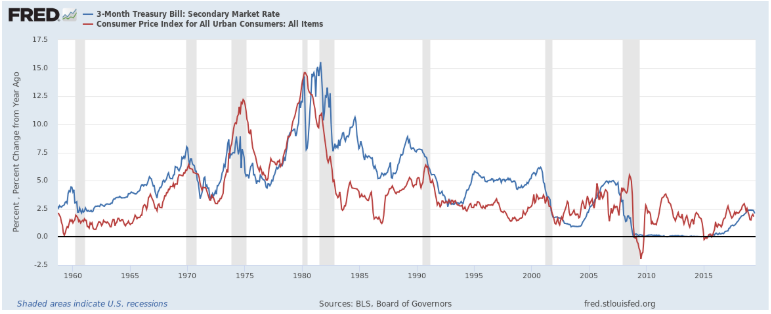

The nominal interest rate, which is the rate that we observe directly, includes two components: the real interest rate and the inflation rate. To the extent that increases in the circulating supply of money drive increases in the rate of inflation, this also drives increases in nominal interest rates. This is known as Gibson’s Paradox. Gibson’s paradox is especially noticeable in years where inflation is volatile. Comovements between the rates from 1965 to 1985 show precisely that the effect of easy money is to raise the nominal interest rates. As inflation estimated by the CPI stabilized, collective movements in interest rates tend to represent changes in preference to save, perception of risk, and investor expectations of real income growth.

Powell’s Options

Commentators are mistaken to think that Powell should reduce the Federal Funds Rate target. The theoretical concern that would justify a decrease in the Federal Funds Rate target would be that the rate of interest set by markets is actually below the Federal Reserve’s target rate. This may be the cause of the current yield curve inversion.

Emphasis on the target rate as being a prime instrument of the Federal Reserve policy leads pundits and President Trump to call for a decrease in the target rate. The theoretical reality described above suggests that Powell has a more efficacious option available to him. An increase in the rate of inflation would prevent the need for a decrease in rates, and could be a significant tool in allowing the market to set rates. Suppose that Powell wants to provide an insurance policy for the market to ensure that low inflation rates do not lead to a testing of the zero lower bound. The simplest option would be for Powell to expand the quantity of money in circulation and let the Federal Funds target rate follow the rate set in the market.

Powell can accomplish this end without expanding the monetary base. Currently, a significant portion of the monetary base has been removed from circulation, instead collecting interest on account at the Federal Reserve. Instead of lowering the target rate, Powell can lower the rate of interest paid on excess reserves relative to the Federal Funds Rate. Funds that would otherwise collect interest as they are held on account at the Federal Reserve would be released for investment in the market. Perhaps some interest rates would fall in the short-run. However, investors would quickly price expected inflation into returns, leading to increases in nominal interest rates.

Currently, the Federal Funds rate is 2.4%. It remains below the upper limit target of 2.5% and is approaching the rate paid on excess reserves, 2.35%. Powell can maintain the corridor system by marginally reducing the rate paid on excess reserves relative to the Federal Funds rate, allowing the inflation generated to push nominal rates higher.

This will simultaneously alleviate stress in the lending market as funds move from the account at the Federal Reserve and into actual investments. This carries with it the additional advantage that Powell could continue winding down the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet without generating deflation. Finally, this will tend to rationalize financial markets as it limits the ability of banks to survive simply by receiving free income from the Federal Reserve.

It is the perfect time for Powell to set right the financial sector and establish a return to normalcy.