Sorry, But Stimulus Policies Will Not Work

Thanks to the coronavirus crisis, stimulus talks are all the rage these days. The steep decline in the stock market and the numerous predictions of serious economic slowdown are enough to trigger all of those who still suffer PTSD as a result of the Great Recession.

The Twittersphere, blogosphere, and opinion pages boom with a high volume of recommendations about what the government should and should not do to boost the economy.

The question I’m left pondering, however, is this one: What can Uncle Sam really do when the main reason people are reducing their purchasing is not a lack of income – unemployment remains very low – but, rather, that they wish to avoid physical contact with others who might have, or who might get, the virus.

Like others, I have no clue what the trajectory of this epidemic will be. I am not a doctor—at least not the kind of doctor who is useful during a public-health crisis. But I can tell you what I know about some of today’s most popular options to stimulate the economy. And for the most part, they won’t work.

Payroll tax holiday

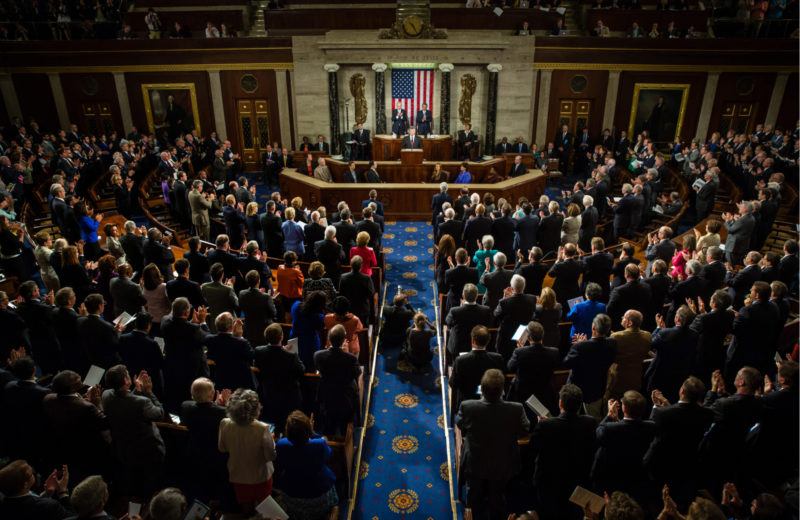

In his March 11th televised address to the nation, President Trump encouraged Congress to consider supporting the economy with payroll-tax relief. This idea has many supporters. However, there are serious reasons to be very skeptical of a payroll tax holiday as a useful fiscal stimulus. Such skepticism is always appropriate, but it is especially appropriate right now.

For one thing – as Milton Friedman made clear – we should never expect much of any temporary tax measures. The Tax Foundation just put out a paper that looks at previous temporary reductions in the payroll tax, and at credits against payroll-tax liability such as the ones tried in 2011 and 2012, and finds that these fiscal manipulations had very mixed results.

There are additional reasons to be skeptical this time around. An employee payroll tax cut might put more money into workers’ pockets, but it’s unlikely to stimulate aggregate demand significantly. The reason is that this additional cash won’t do much to convince consumers to go to the likes of restaurants, supermarkets, airports, and automobile dealerships as long as the epidemic is raging.

Equally pointless would be tax relief – or subsidized loans – to employers. Yes, during the crisis many fundamentally healthy firms might encounter liquidity challenges. Such firms, however, would have no trouble borrowing the necessary liquidity from banks and other capital-market sources. Supplying such liquidity is among the core functions of capital markets. Nothing about the coronavirus crisis renders capital markets unable to perform this worthwhile function.

Stimulus by government spending

Last week, the administration approved a roughly $8 billion emergency spending to develop medical treatments and to prevent new infections. The Trump administration has so far stayed away from proposing any additional government support as a way to support the economy. That’s a good thing.

According to the economics literature, even if one grants that government spending can trigger sustainable economic growth in times of crisis, the way the money is spent is key. For government spending to boost the economy, the spending should be timely, well-targeted, and temporary. Unfortunately, in real life, this does not happen. Take the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. That stimulus bill directed $831 billion in spending toward, among other purposes, to create jobs through infrastructure-construction projects.

According to Keynesian theory, for the spending to be targeted, the money should be injected into the economy so that companies that receive the funds will hire workers who don’t have jobs in order not only to put them back to work but to give them incomes to spend. Yet that’s not what happened in 2009.

The data also show that stimulus money wasn’t targeted to those areas with the highest rates of unemployment. In fact, a majority of the spending was used to poach workers from existing jobs in firms where they might not be replaced.

Economists also found that instead of using the money to increase government purchases, and to fund shovel-ready projects that would put people back to work, many states chose to use the money to close their budget gaps. This choice meant that the money went to keeping schoolteachers in their jobs and paying public sector workers, rather than creating additional jobs in the private sector.

Such spending is also rarely temporary. Part of the reason is that politicians use crises to push spending they wanted all along. Another reason is that once the spending starts flowing, it gives rise to special interests who do everything they can to ensure the spending doesn’t stop. For all these reasons, and a few others, a review of historical stimulus efforts shows that ‘temporary’ stimulus spending tends to linger. Two years after the initial stimulus, 95 percent of the new spending becomes permanent.

And forget about timely. The last time around it took months and months to send the money out for spending on allegedly shovel-ready projects. There are many reasons for such delays. One factor was documented recently by Eli Dourado in a must-read piece called “Why are we so slow today?” He writes that:

“… part of the answer is environmental review. In the United States, a statute called the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) requires review of major federal actions “significantly affecting the quality of the human environment.” Federal actions include issuing of federal permits or approvals to private projects, and therefore NEPA effectively applies to these private projects as well. In addition to the federal NEPA, at least 20 states and localities have statutes, known as “Little NEPAs,” that require similar review.”

Dourado looks at how the burdensome review processes affected the timing of the stimulus in 2009 and finds that:

“The stimulus in the ARRA ended up being subject to around 193,000 NEPA reviews including over 7,200 environmental assessments and 850 EISs. During the time the reviews were being performed, no funds for the projects could be disbursed and no work could begin.

The entire purpose of fiscal stimulus is to rapidly inject funds into an economy that needs it to keep levels of spending stable. Because large portions of the stimulus couldn’t happen in a timely manner, it was rendered less effective, leading to a long and painful recovery. Environmental review, therefore, was partially responsible for the severity of the recession.”

The bottom line is that even if you believe that spending can stimulate the economy in theory, you should be skeptical of it in practice.

What is left?

First, we should give up the fantasy that the government can ‘stimulate’ the economy out of this particular crisis. Second, Congress, the Administration, their advisors, pundits and journalists should not exploit this crisis to subsidize special interests or hand out favors to those seeking to achieve policy aims unrelated to the outbreak. No one should try to get their pet policy preferences implemented either; I am thinking of you, “Medicare for All,” “a hike to the Medicaid matching rate” and “pass a permanent and universal government funded paid leave program.”

The best that the government can now do, if it wishes not to act either pointlessly or destructively, is to help the most vulnerable Americans by tweaking some existing spending programs. It can, for example, help lower-income workers with temporary and targeted funding, such as to pay for sick leave for the relatively few workers who don’t now have access to this fringe benefit.

Furthermore, if you want to boost the stock market, an announcement that the president is immediately lifting all tariffs will go a long way to jolt investor optimism. While this move might not do much in the short run, it will accelerate and fortify the recovery once it begins, especially because other countries are likely to follow the U.S. and lower their tariffs.

Most foundationally, the most urgent health-related step is for the federal and state governments to remove all restrictions on private-sector experimentation while trying to find solutions to this epidemic. For instance, the burdensome and slow government approval process is still preventing private laboratories in the U.S. from conducting their own tests. That’s crazy.

I assume the same is true about finding a vaccine for this virus.

Unleashing human creativity – guided by prices and profits in competitive markets – is our best hope not only for bringing this crisis to an end as soon as possible, but also for building safeguards that will help us avoid, or to deal expeditiously with, any such future crisis.