Solid Jobs Report Suggests Moderate Growth

U.S. nonfarm payrolls added 164,000 jobs in July, after an increase of 193,000 new jobs in June. The June gain was revised downward by 31,000 from an initial estimate of 224,000 jobs. Combining the last two months with a 10,000 downward revision to the weak May gain of just 62,000, the three-month average gain in payrolls came in at 140,000 in July. However, over the past 12 months, the average is a healthy 187,000.

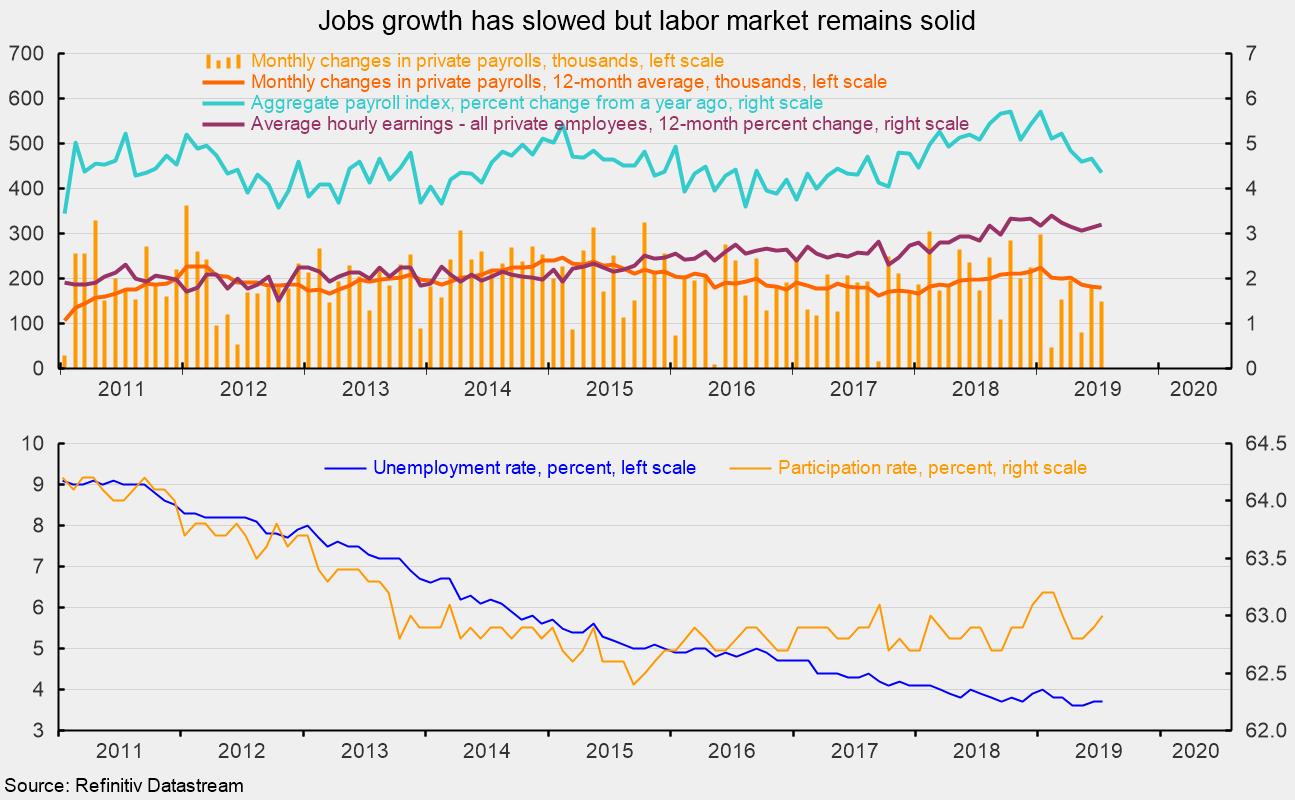

For the private sector, nonfarm payrolls added 148,000 in July following a gain of 179,000 in June. On a three-month-average basis, private payrolls added 136,000, and over the past year, the average gain is 180,000 (see top chart). The 12-month average has ranged between 150,000 and 300,000 since mid-2011 and is just below the five-year average of 195,000. Despite the slightly slower average rise over the past year, job creation remains on a solid trend pace. The latest report on the labor market suggests cautious optimism for continued economic expansion.

Goods-producing industries added 15,000 jobs in July, below the monthly average gain of 31,000 over the past year. Manufacturing led with an addition of 16,000, as durable-goods industries added 12,000 and nondurable-goods industries added 4,000. Mining and logging industries lost 5,000 jobs after dropping 1,000 in June.

Within private service-producing industries, which typically account for the lion’s share of job creation, payrolls rose by 133,000 workers, led by a 50,000 gain in health care, a 38,000 jump in professional and business services, and a gain in financial-services industries of 18,000 jobs.

Weakness continued for the retail industry, which lost 4,000 jobs for the month, about in line with the average 5,000 job loss per month over the past year. Information-services industries cut 10,000 jobs in July.

Public sector employment rose by 16,000 in July, ahead of the average monthly gain of 7,000 jobs over the past year. The gains came almost entirely from local governments (up 14,000) while federal government jobs rose by 2,000.

The unemployment rate held for the second consecutive month at 3.7 percent, just slightly above the 3.6 percent low since December 1969 (see bottom chart). The labor force participation rate rose 0.1 percentage point to 63.0 percent in July as 370,000 people entered the labor force. The participation rate briefly dipped to a cycle low of 62.4 percent in September 2015 and has spiked as high as 63.2 recently but has been essentially trending flat between 62.7 percent and 63 percent since late 2013 (see bottom chart). The labor force participation rate had been as high as 67.3 percent in 2000.

Average hourly earnings rose 0.3 percent in July, pushing the 12-month change to 3.2 percent, up from 3.1 percent last month (see top chart). Average hourly earnings growth has been slow compared to previous cycles, especially given the low unemployment rate, but it has been accelerating gradually since late 2017. While that is good news for employees and consumer spending, it could be a problem for employers as rising labor costs squeeze profits.

Combining payrolls with hourly earnings and hours worked, the index of aggregate weekly payrolls rose a modest 0.1 percent in July and is up 4.4 percent from a year ago (see top chart). This index is a good proxy for take-home pay and has posted relatively steady year-over-year gains in the 3.5 to 5.5 percent range since 2011 but has been decelerating recently. Continued gains in the aggregate-payrolls index are a positive sign for consumer income and spending and are likely to support continued economic expansion.

Overall, the July jobs report was solid though not spectacular. Other data paint a picture of generally benign economic conditions. Second-quarter gross domestic product growth was stronger than the headline suggested but still modest by historical measures, and consumer price increases remain very modest and below the Fed’s target. The data alone do not justify the recent Fed rate cut. However, the Fed cut rates with the justification of wanting to provide insurance against slowing global economic conditions and heightened uncertainty regarding trade policy. This type of justification may lead to a more difficult position down the road. Will the Fed then raise rates when uncertainty diminishes or global growth picks up, regardless of domestic economic conditions? The cut does not mesh with a data-driven framework and is likely to lead to more confusion over future policy decisions.