Not All Government Spending is Stimulus

For months, Congress has debated proposals for an economic stimulus bill to follow March’s Coronavirus Aid Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act. Federal Reserve officials have also called for fiscal stimulus to complement the Fed’s monetary policies.

Although these fiscal policies are labeled as economic “stimulus,” they are better described as “relief” packages. The goal of these proposals is to provide aid to out-of-work Americans who have been harmed by the coronavirus and restrictive lockdown policies. Such programs, however, are unlikely to stimulate economic activity.

Stimulus vs. Relief: When does fiscal policy stimulate the economy?

The two most common measures of economic activity are employment and production (Gross Domestic Product or “GDP”). The government can spend money to buy or produce public goods and services. Because of this spending, the government and the companies from which it buys tend to hire more employees. Thus, government spending on public goods and services can stimulate economic activity in terms of production and employment (although it may be offset by monetary policy).

Some fiscal policies, however, encourage people not to work and produce. One example is when the government increases benefit payments to the unemployed. Such payments might marginally increase consumption by those receiving the funds, but the direct effect is to discourage people who are out of work from finding a new job.

Relief payments can be vital to helping the recipients through these difficult economic times, especially when government restrictions force people to stay at home or prevent businesses from operating. Individuals cannot work while such restrictions are in effect, even if they want to. Relief programs provide benefits to unemployed Americans, but they do not help to stimulate the economy.

Proposed “Stimulus” Bills

There are multiple proposals before Congress to increase fiscal stimulus spending. In October, the House of Representatives passed a revised version of the Health and Economic Recovery Omnibus Emergency Solutions (HEROES) Act that would increase spending by $2.2 trillion. A smaller bill of $500 billion was proposed but voted down in the Senate. Forthcoming legislation is likely to be a compromise between these two proposals.

Spending in the HEROES Act falls into three categories. First, the bill allocates funds for coronavirus testing and treatment of $75 billion, a large dollar amount but a small percentage of the total.

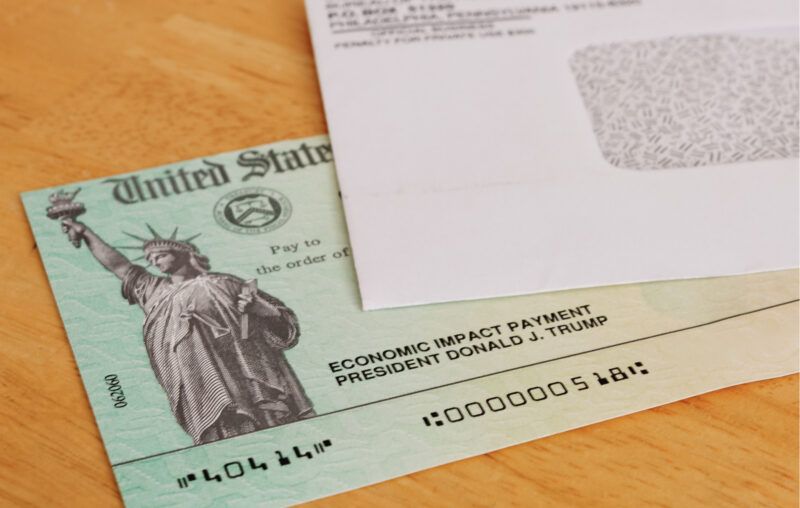

Second, the bill would revive several programs from the CARES Act, including the Paycheck Protection Program, an added $600 per week increase in unemployment benefits, and one-time direct payments of $1,200 to eligible Americans. These are relief payments, not stimulus.

Third, the HEROES Act contains trillions of dollars of wasteful spending that is neither relief nor stimulus. This includes subsidies for US airlines and bailouts for state and local governments that have been overspending for decades.

Little, if any, spending from these so-called “stimulus” bills will actually stimulate the economy.

The Fed on Fiscal Stimulus

Fed Chair Jerome Powell has repeatedly called for Congress to expand its fiscal stimulus spending as a necessary complement to the Fed’s own initiatives. It is often unclear, however, whether he is actually calling for true stimulus spending or simply for aid and relief.

Powell recently said that fiscal policy is “needed to avoid further spread of the virus and help individuals who, with the expiration of the CARES Act payments, are seeing their savings dwindle.” He praised “federal stimulus payments and expanded unemployment benefits, which provided essential support to many families and individuals.” Although he does cite economic benefits such as supporting household spending, Powell’s descriptions seem to emphasize the relief aspects of these programs rather than their stimulative effects.

Powell has also voiced support for mask mandates and other restrictive policies. He claims that “There’s actually enormous economic gains to be had nationwide from people wearing masks and keeping their distance.”

While it is possible that such policies might help suppress the coronavirus and improve economic growth over the longer run, the direct effects of restricting workers and consumers are clearly negative for the economy. In addition, recent evidence shows that the benefits of mask mandates and lockdown restrictions have been greatly overstated. Fed officials would do best to focus on their own monetary policies and avoid topics on which they have little expertise such as lockdown restrictions and appropriate fiscal policy.

Americans should be skeptical of claims by Congress and the Fed of fiscal spending “stimulus.” Relief spending would be a much-needed blessing for many Americans. But paying people not to work does not stimulate the economy.