No, Lockdowns Do Not Foster Creative Destruction

The field of economics is something of a paradox. Decried as thorny and opaque, the least informed person still feels qualified not only to weigh in on, but to correct dedicated practitioners on, economic matters. (The novices aren’t always wrong, but often are.)

We can look to two explanations for this economic haughtiness. One, economic predictions are so wrong––so regularly––that expertise is not respected by the layman and tried-and-true explanations are discarded readily. And two, because economics is so closely tied to money and virtually every human being has used money, it’s simply not clear why it all should be so complicated. The general public has fallen into a rut of oversimplification, to be sure––but such errors are not just committed by amateurs.

Take top economic adviser to the former president Larry Kudlow, for instance. Kudlow (who should know better) spoke in an October interview with Fox Business host Stuart Varney about the new businesses arising as a side effect of growing unemployment. This, he said, was a shining example of “creative destruction:”

“I saw something else today, one of the smart Wall Street people are talking about it. And it’s an odd thing because the talk is that a lot of folks who became unemployed, all right, most regrettably but they’re sticking with it and starting new businesses. They’re going to be small businesses. But that’s the great part of American capitalism, gales of creative destruction. I just love that new business start-up story.”

Similarly, an NPR “Planet Money” article made the following observation as new business applications climbed in the third quarter of 2020:

Most of these new businesses are seizing opportunities created by the weird coronavirus economy – an economy where people don’t really want to do stuff face-to-face anymore…[and] it may be good news that new businesses are growing out of the ashes of old businesses. Economists have a term for this. They call it “creative destruction.” Harvard University economist Joseph Schumpeter…described it as a process of “industrial mutation…that incessantly revolutionizes the economic structure from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one.”

The NPR writers are correct about what creative destruction is. They are correct in the way that Joseph Schumpeter described it. But what we have been seeing, and continue to see, is not creative destruction.

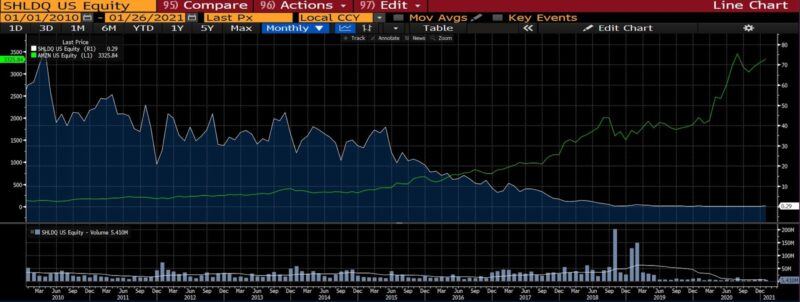

This is not creative destruction. New business formations vs. bankruptcy filings, 2010 – today,

and from 2019 – today.

New businesses being created are a welcome (indeed wonderful) silver lining to the awful effects of pandemic mitigation policies. But it’s not Schumpeterian “creative destruction” in action. Schumpeter’s conception of market economies held that entrepreneurs innovate, undermining and sometimes destroying the value and position of long-standing firms through competition. The basis of that competition is often multifaceted. New firms do not only have technological advantages, as the standard examples hold, but organizational or financial ones as well.

This is an example of creative destruction in the retailing sector: Amazon vs. Sears, 2010 – today. (Stock prices are multiples of earnings, and comparing stock trends roughly approximates the shift in commercial dominance.)

Entrepreneurs jumping into the scorched earth where inconceivably heavy-handed measures leveled or damaged over 100,000 firms has as much to do with creative destruction as real estate developers erecting new structures after a bombing raid. This was not creative destruction, in which consumers are the ones who pick winners and losers. This was a forceful closure of certain sectors of the economy, imposed from the top-down, an artificial sieve filtering out all but the luckiest and most resilient firms. Who’s to say which businesses would have survived in a fairweather economy?

Far too easily, we fall into the trap of the broken window fallacy. Put forth by Frédéric Bastiat in 1850, the parable illustrates why neither destruction nor funds spent to address destruction are a net benefit to society. Sure, a broken window provides a business opportunity for a glazier, but what might the shopkeeper have spent his money on if his window did not need to be replaced? He could have bought shoes from a cobbler, for instance, stimulating other parts of the economy and expressing his true preferences.

If Kudlow and his ideological fellow travelers believe that lockdowns or other exogenous measures foster growth via an artificial form of imposed disruptive innovation, worrisome policy implications arise. Why, for example, shouldn’t random closures of businesses, prohibitions on uses of certain technologies, or sudden regulatory changes be instituted to winnow entire portions of a given sector or industry? Why shouldn’t we launch an artificial survival-of-the-fittest game every few years, given that new businesses would emerge from the wreckage? There lies the faulty logic of Kudlow and company.

Stay-at-home orders are in the same category as regulations, taxes, fees, and other government or state agency encroachments on commerce, albeit more severe and fast-acting. No one would call entrepreneurial activity in the wake of policy-induced business failures evidence of the so-called Schumpeterial Gale, nor does this qualify. In Schumpeter’s words, market economies are

by nature a form or method of economic change and not only never [are] but never can be stationary … The fundamental impulse that sets and keeps the capitalist engine in motion comes from the new consumers’ goods, the new methods of production or transportation, the new markets, the new forms of industrial organization that capitalist enterprise[s] create … the opening of new markets, foreign or domestic, and the organizational development from the craft shop and factory to such concerns as US Steel illustrate the process of industrial mutation that incessantly revolutionizes the economic structure from within[.] [emphasis added]

To be sure, this is not Mr. Kudlow’s first curious interpretation of economic principles or theory. Despite nominally supporting free markets, he supported government bank bailouts in 2008 as well as the government taking equity stakes in large businesses in March 2020. And the awful predictions he’s made are the stuff of infamy.

Conflating the transformative power of entrepreneurs and markets with the rush of businesspeople to fill a gap left by major policy errors and despotism does more than play fast and loose with economic theory: it has exculpatory overtones. When recovery from the effects of lockdowns, stay-at-home orders, and other draconian measures finally comes, it will be in spite of, not with the help of––and certainly not because of––county, state, and Federal government measures.