Natural rate of interest: Is it that low?

One of the open questions since the subprime crisis is whether or not the natural rate of interest is as low as the federal funds rate. The natural interest rate is the rate that equilibrates production over time. However, this concept is more subtle than output being equal to potential output– it also implies that production is distributed efficiently over time.

If it is the case that the natural rate of interest is, in effect, close to zero, then the Federal Reserve’s policy of maintaining a low federal funds rate target could be an adequate one. But, if this is not the case, then the Federal Reserve might be pushing interest rates below their equilibrium level and imposing costly imbalances on the economy.

In a new working paper published by the BIS, Juselius, Borio, Disyatat, and Drehmann build on the well-known estimation of the natural rate made by Laubach and Williams and argue that a problem with the usual treatment of this issue is incomplete in a way that bias the results. The missing piece, these authors claim, is the financial sector. By focusing almost exclusively on the real sector, the implied reading is that the real interest rates are independent of central banks’s policies. But if there is a connection between the financial sector and the real economy then that is no longer the case. In fact, the authors sustain that crisis, especially those that coincide with a banking crisis, have a permanent effect on output. Even if the growth rate goes back to its previous value, there is a negative level effect.

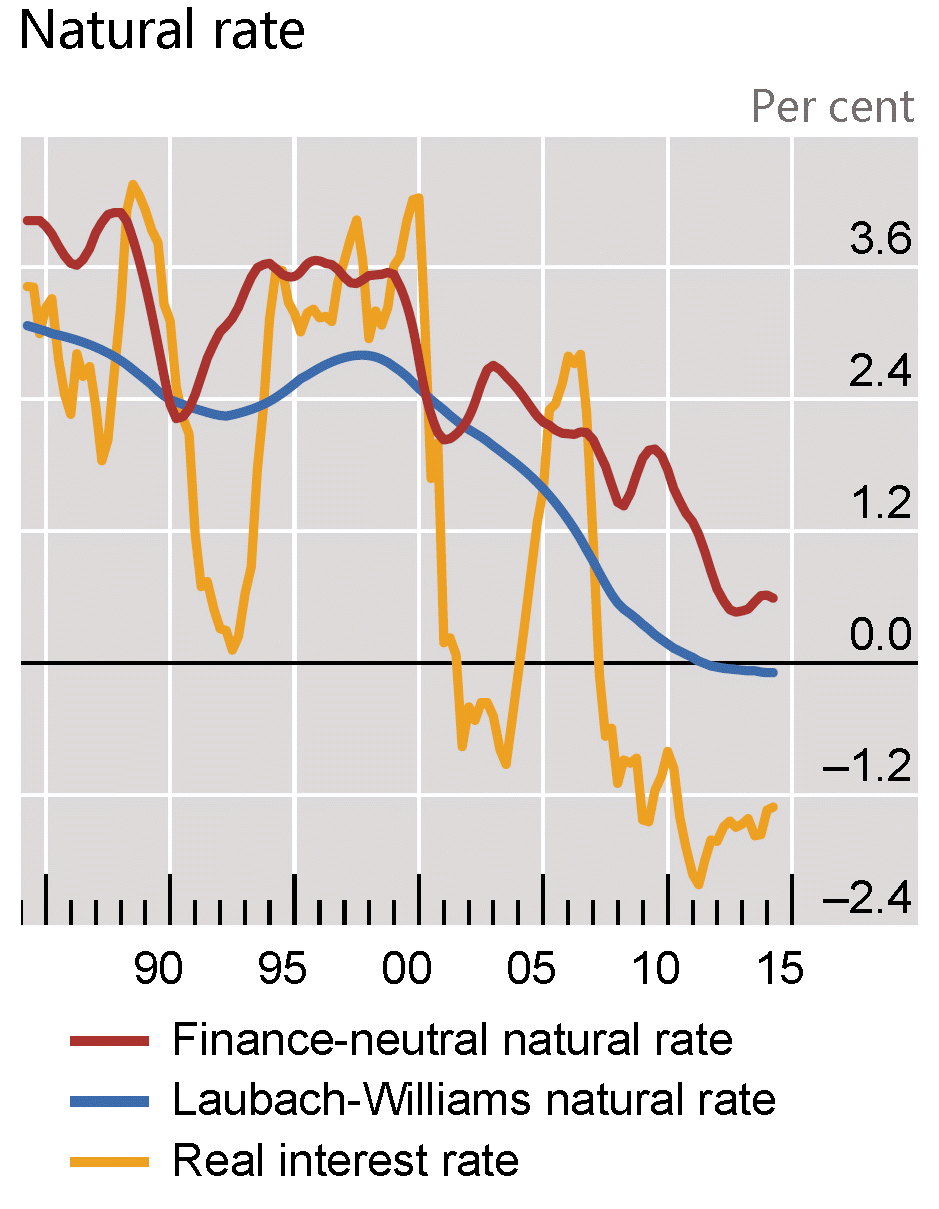

But maybe the main conclusion of this study is that, by adding financial variables to the estimation of the natural rate, then the usual calculations are consistently downward biased. In other words, estimations of the natural rate such as those made by Laubach and Williams yield overly low values that can mislead the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy (figure is taken from page 19).

According to this expanded estimation, the equilibrium interest rate is around 0.5%, not 0%. Furthermore, the graph shows that the Federal Reserve pushed down the interest rate more than it should have, and again kept it too low for too long.

What type of disequilibrium, if any, might this produce?

The conventional reading is that inflation is a sign that monetary policy is too loose, but it could also be the case that an excess of the money supply is not captured soon enough in inflation measures. Does that sound familiar? Just think back to the subprime crisis where there was a housing bubble but no clear signs of inflation.

You can download the paper here.