More Sensational Reporting on COVID-19 Estimates

Last week, media outlets were widely reporting that the Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team had predicted 2.2 million Americans and 510,000 Brits would die from the coronavirus. In fact, the authors of the study had described that outcome as “unlikely,” resulting only if there were no behavioral or policy responses to the pandemic.

And, as I noted at the time, we were already taking steps to reduce the number of deaths from COVID-19.

This week, following testimony by Imperial College London’s Neil Ferguson before the UK’s parliamentary select committee on science and technology, the pendulum has swung the other way.

A Washington Examiner headline reads: Imperial College scientist who predicted 500K coronavirus deaths in UK revises to 20K or fewer. On Twitter, former New York Times reporter Alex Berenson, who is quoted in the aforementioned article, goes even further. He claims the “remarkable turn from Neil Ferguson” is “*interesting*” insofar as “Ferguson gives the lockdown credit” since the lockdown was only implemented two days ago “and the theory is that lockdowns take 2 weeks or more to work.”

Just as the Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team did not initially predict so many deaths, it has not revised down its estimate in the time since. Those making such claims fundamentally misunderstand the science of modeling.

Ferguson did say that the number of deaths in the UK “would be unlikely to exceed 20,000.” But, as he noted in yesterday’s hearing, that is “not a detailed projection based on the most current data” but rather comes directly from the report released on March 16. It is not a new, revised estimate. It is the same old estimate. How can that be?

The original study begins with a benchmark case, where the authors assume (implausibly) that no one changes their behavior and no policies are adopted to deal with the virus. The benchmark case is not offered as a prediction of what will be. Again, the authors clearly write that such an outcome would be “unlikely.” Rather, they use this benchmark case to estimate the marginal effectiveness of various behavioral and policy responses.

Suppose, for example, that the model estimates 510,000 deaths in the benchmark case when the reproduction number, R0, is 2.4. Suppose, further, that the model estimates 90,000 deaths under Response 1A, where those experiencing symptoms stay home for 7 days (case isolation), those sharing a house with someone experiencing symptoms stay home for 14 days (home quarantine), and everyone reduces contact with those outside their household, school or workplace by 75% (social distancing) any time the weekly number of new COVID-19 cases diagnosed in ICUs exceeds 60 and continue to do so until the weekly number of new COVID-19 cases diagnosed in ICUs falls below 45. The model, therefore, estimates the marginal effectiveness of Response 1A is (510,000-90,000) = 420,000 lives saved, or a (420,000/510,000) = 82.34% reduction in the total number of deaths, if R0 is 2.4.

Note that we would not be able to calculate how many lives the model estimates are saved by the response without considering what the model estimates in the absence of the response. That is why the authors begin the analysis with the benchmark case, where no one responds to the virus.

So, how many deaths did the Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team estimate in their March 16th study? The answer is: it depends.

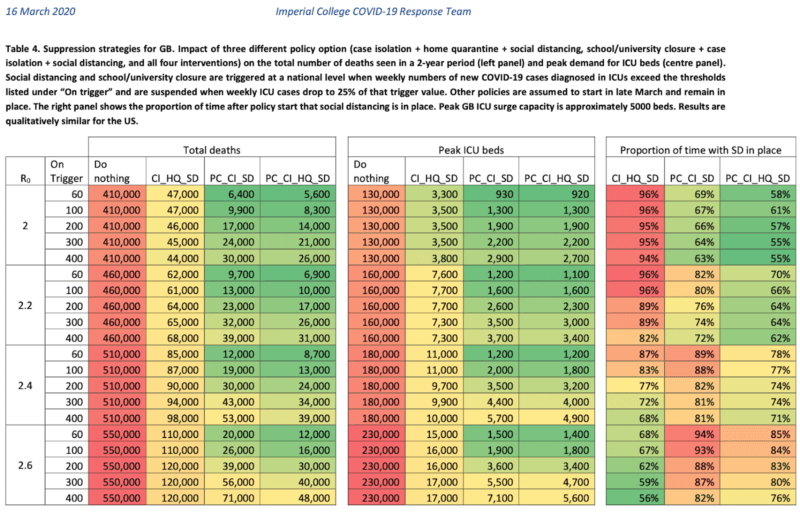

In the left hand panel of Table 4, reproduced from the original study below, the authors present the estimated number of deaths in sixty-four scenarios. Specifically, they consider (1) three response regimes under five response triggers given four possible values of the reproduction number and compare these to (2) the four no-response cases given the same four possible values of the reproduction number. Their estimates range from 5,600 to 120,000 deaths for the various response regimes considered.

When moving from estimates, like those included in Table 4 above, to predictions about what will likely happen, one must take a position on which of the possible parameterizations of the model–that is, the reproduction rate, response regime, and response trigger–looks most like the world we will live in over the relevant time horizon; or, alternatively, one must make assumptions about the likelihood of each potential outcome.

Today, “with effectively a lockdown with intense social distancing strategy” in the UK, Ferguson believes the number of deaths is “unlikely to exceed 20,000” and noted that “it could be substantially lower than that.”

That view is entirely consistent with the earlier analysis put out by the Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team. And, to the extent that Ferguson has revised his prediction in the past week, it is at least in part because the likelihood of potential outcomes has changed.

“We have ruled out some scenarios actually in our paper,” he said. “But there is still uncertainty about the extent of asymptomatic infection.”

While the 20,000-deaths-in-the-UK estimate is not new, Ferguson did shed some light on the number of “excess deaths” likely to result from COVID-19–that is, the number of deaths that would not have happened otherwise.

“It might be as much as half to two-thirds of the deaths we are seeing from COVID-19,” he said, “because it is affecting people particularly either at the end of their lives or with poor health conditions.” Many of those people would have died from other causes this year, like the seasonal flu, had they not been infected by COVID-19.

Finally, Ferguson’s testimony reiterates the need to think carefully about the tradeoffs many of my AIER colleagues have been writing about. “The optimal goal,” he said, “is to […] balance mitigating the health impact of the epidemic against the economic impact,” which results in real hardships for real people and, in some extreme cases, will even bring about early deaths of its own.

The risks of COVID-19 are real. And we should certainly take steps to reduce those risks. But we should not sacrifice everything out of fear of losing something.

Alas, such sober analysis does not lend itself to the sort of attention-grabbing click pieces that pay the bills for journalists. So we should continue to expect sensational reporting on the global pandemic. Discount what you read, accordingly.