Money as an Evolving Social Contract

Money is a social contract. Control over money is the legal privilege of the monetary authority. Those who use it appreciate the benefits well enough to accept the influence of this authority over the monetary system. Its existence as a social contract, however, does not imply that authorities in this arrangement are above reproach. Brian Albrecht has identified this in articles from positive and normative perspectives. In this article, I will consider influences on the path of evolution of this social contract. This evolution consists of a dynamic conversation between interested parties.

An idealistic vision of politics sees government as responsible for carrying out the social contract. A well-developed view is presented by economist James Buchanan, whose contractarian theory also underlies his theory of economic development. According to Buchanan, the social contract is a de facto outcome that naturally emerges from the interaction of purposive agents who may wield force, provide value to one another, or both. A participant forms expectations concerning the abilities and strategies of others, employing the strategies he or she believes will lead to a relatively desirable outcomes given the existing arrangement. The equilibrium that results is coordinated by this de facto social contract that, with requisite stability, may become further ingrained in social relations and even evolve into a formal institution. (In a footnote, Buchanan notes that he borrows from Henry Maine’s concept of the “quasi-contract,” where “there is no implication of explicit agreement, but the relationship is such as to make the contractarian framework for discourse helpful.”)

If the social contract is to have any meaning, it must be capable of absorbing the demands of participants who subject themselves to it. It is not enough that A can oppress B because of his command over a violent brigade or omnipresent administration or position atop the hierarchy. B will often cooperate with A to develop a social contract that improves the position of both parties. Even the strongest militaries learn that cooperation with locals will often achieve the goals of their organization at relatively low cost.

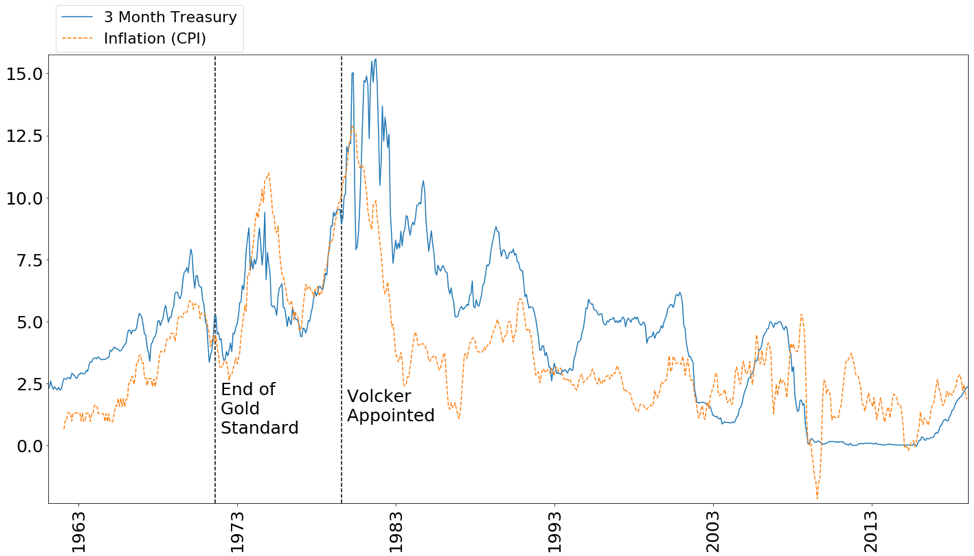

Authorities at the Federal Reserve have learned the same lesson concerning their duties in the social contract known as money. Much of the power that Keynesian monetary theorists thought that the state could exercise through monetary policy proved illusory once international participants in the Bretton Woods system saw U.S. monetary policy as not maintaining their interests. The old system broke, and the U.S. suffered a decade of relatively high and volatile inflation rates as a result.

In an evolutionary social contract, participants can change the rules when enough perceive that the system is out of balance. Thus, many nations began to withdraw their gold from the U.S. when they did not trust that U.S. monetary policy promoted their own interests. This occurred on several margins during the 1970s. First, nominal interest rates rose in response to inflation. Investors may simply accept that the central bank has violated its role in maintaining monetary stability and, in turn, demand higher interest rates that compensate for inflation created by the central bank. Second, investors may find ways to circumvent laws that prevent their demand for higher interest rates from being satisfied. This occurred with the development of the Euro-dollar market, which enabled depositors to earn the market rate of return despite Regulation Q, which placed a ceiling on interest rates paid to depositors. If participants in a social contract are unhappy with an outcome or believe that their position has been unjustly compromised, they will seek to improve their situation by maneuvering within the game being played or by transforming the game.

In both cases, authorities came to recognize their responsibility to maintain the integrity of the social contract. Paul Volcker was appointed to the Federal Reserve in 1979. Volcker is widely credited for reducing the rate of inflation and, consequently, the height of nominal interest rates. Even after the rate of inflation fell, the level of nominal rates did not again coincide with inflation for more than a decade. The government had violated the social contract, and investors appear to have accounted for this in their expectations.

Similarly, Congress was forced to recognize that Regulation Q was creating more problems than it was solving. At the close of 1980, a period defined by especially high rates of inflation, Congress legalized NOW (negotiated order of withdrawal) accounts that allowed depositors to invest in the Euro-dollar market. These operated like deposit accounts, providing a high level of liquidity and rate of return for account holders. The inflation caused by easy monetary policy led investors to seek high rates of return to offset the inflation, even if the legality of these investments was unclear. The law had failed to prevent the development of the Euro-dollar market. Legal recognition of the fact, as opposed to opposition, was the appropriate course of action.

The government faces similar problems today. The Powell-led Federal Reserve has begun to unwind the central bank’s balance sheet, allowing securities to mature and selling others. Powell is attempting to maintain the Federal Reserve’s supposed role in maintaining a low to moderate rate of inflation. In affirming this commitment with action, he strengthens the confidence of investors that they do not need to prepare for a violation of the monetary social contract. Recent comments from Powell, however, show that this resolve may waver in time of crisis.

As with Regulation Q, financial regulators are struggling to cope with the development and adoption of cryptocurrencies. These financial instruments may provide a new source of liquidity and, in some communities, operate as a commonly accepted medium of exchange. Many businesses are being developed that integrate blockchain and cryptocurrency, all while federal regulators have been unable to define a coherent regulatory framework. Innovators and entrepreneurs have made their move; now policy makers will need to adjust their frame to account for this reality.

Framing money as an evolutionary social contract provides a window into the dynamics that develop within a market and between investors and regulators. Fundamental to the healthy development of the monetary social contract, and the game of exchange more broadly, is respect for property rights and freedom to innovate. Violations of the rules of the game by regulators are, as a simple matter of fact, integrated into the strategy of participants who bear the consequences of policies implemented by these regulators. Likewise, innovations by entrepreneurs are often integrated into the legal framework even after being practiced in legal ambiguity. Both of these types of actors continually reorient their approach to a changing environment, legitimating the contract through ongoing participation.