Meet the New Fed, Same as the Old Fed: Jerome Powell’s Inflation Revelation Falls Flat

The most important part of Fed Chairman Jerome Powell’s address was what he didn’t say.

At the central bank’s virtual Jackson Hole symposium, Powell announced that the Fed is embracing an average inflation target. “Our longer-run goal continues to be an inflation rate of 2 percent,” he affirmed. “However, if inflation runs below 2 percent following economic downturns but never moves above 2 percent even when the economy is strong, then, over time, inflation will average less than 2 percent…Therefore, following periods when inflation has been running below 2 percent, appropriate monetary policy will likely aim to achieve inflation moderately above 2 percent for some time.”

In other words, the Fed is signaling its willingness to play catch-up when implementing monetary policy. To help markets achieve full employment, it will no longer let bygones be bygones.

Many Fed watchers anticipated Powell’s announcement, believing it represents a significant shift in Fed operating procedure. But if we dig a little deeper we discover a notable omission, which may leave markets and Fed-watchers feeling underwhelmed.

Average inflation targeting is probably an improvement over what the Fed had before. A well-executed average inflation target is good for anchoring expectations, which in turn makes it easier for households and businesses to contract. If the Fed is no longer willing to shrug its shoulders when it misses its target, markets will find it much easier to make long-term plans. If the Fed were not willing to allow catch-up inflation, markets would still have to spend lots of time and energy watching the Fed, because any deviation from its target can have permanent consequences. In contrast, temporary deviations away from 2% inflation aren’t a problem if the Fed promises to make it up.

However, that an average inflation target is an improvement in theory does not mean the Fed can pull it off in practice. Powell is clearly concerned with boosting the Fed’s credibility, but worryingly, he does not include in his address a means to increase it. This may be the Achilles’ heel of the whole plan.

Powell recognizes the Fed must create a stable framework for future market activity. While this move makes sense, we have good reasons to be skeptical that it will work. Credibility is hard to build and easy to lose, and the Fed doesn’t have a lot of credibility right now. Despite adopting a 2% inflation target under then-Chairwoman Janet Yellen, the Fed consistently failed to hit its mark. As Powell admits, the Fed’s “persistent undershoot of inflation from our 2 percent longer-run objective is a cause for concern.”

Furthermore, the Fed’s experiments with fiscal policy during the coronavirus crisis—direct lending to small- and medium-sized businesses, large corporations, and state and local governments—shows it’s prone to wander off the straight-and-narrow when it comes to its mandate. This lack of focus also harms the Fed’s reputation. Given these problems, it’s hard to see why Powell’s announcement, by itself, would convince markets that the Fed finally means business.

Powell’s address lacks a viable strategy for persuading markets that the rules of the game have changed. This is no monumental policy shift. It’s fiddling while Rome burns. The problems with the Fed, which go back to the 2008 financial crisis if not earlier, are institutional. Why did the Fed fail to stabilize markets after the financial bubble burst, dooming America to a dismal recovery? Why did the Fed neglect macroeconomic stability following the spread of Covid-19, focusing instead on detrimental credit allocation? The answer is that the Fed’s decision procedure is completely unanchored from a system of rules that would force the Fed to keep its promises.

Powell wants to have it both ways, but can’t. Only a rule-bound Fed can credibly commit to an average inflation target. While central bankers would love it if the market treated their strategies as credible without internal reform, we’ve learned the hard way that this just doesn’t work. Powell’s Fed is probably trying to retain some flexibility in the event of future macroeconomic turbulence, which is why the target change didn’t come with an accompanying procedural change. But given the Fed’s unimpressive record with discretionary monetary policy, the absence of a commitment mechanism means it’s likely to continue fumbling the ball.

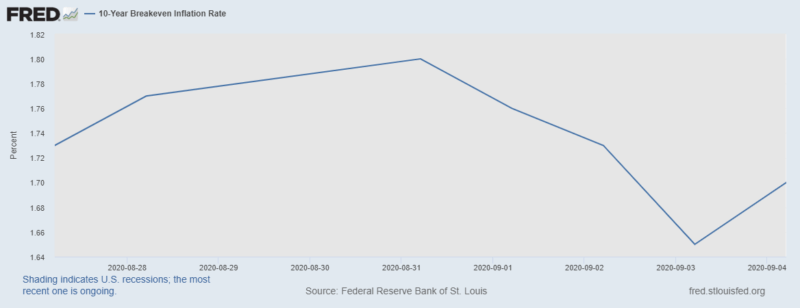

Talk is cheap. If Powell wants markets to trust the Fed, the Fed first must go further than a mere verbal pledge. Policy announcements without accompanying process changes aren’t very credible. Notably, after a brief rally, inflation expectations have actually fallen since Powell’s address:

Granted, it’s not yet been two weeks since the announcement. But what we’re seeing so far suggests markets are unimpressed.

If it’s serious about a 2% inflation target, the Fed will have to do better than a pep rally. We were promised meaningful change; what we got was the same old song and dance.