Krugman’s Zombie Idea: We Owe It to Ourselves

Paul Krugman coined the term “zombie ideas” to describe “policy ideas that keep getting killed by evidence, but nonetheless shamble relentless forward, essentially because they suit a political agenda.”

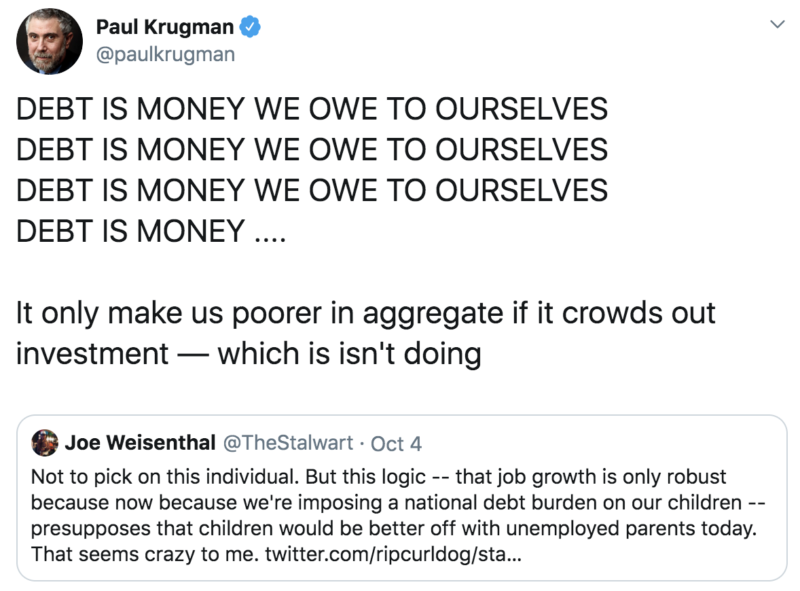

Krugman has revived one of his favorite zombies: the notion that high government deficits aren’t dangerous in the way that an individual incurring heavy debt is because the national debt is “money we owe to ourselves.” He doubled down on his claims in response to an article comparing the dangers the debt poses to future generations to climate change.

Krugman has repeatedly written on this topic at his blog (see here and here). It was a common refrain of his during the Eurozone crisis and in the aftermath of the Great Recession when there was a bipartisan push to cut future deficits to prevent future Greek-style debt crises.

As with most myths, there is a grain of truth to the claim. National debt does differ from the debt individuals and households incur in a few notable ways. Individuals have a finite lifetime to incur and repay their debts. Governments don’t; they can pass debt onto future generations. So long as people are willing to lend it money and the government can service debt as it comes due, government debt can persist in perpetuity. And to the extent that the debt is owned by domestic citizens, the money that is used to repay the debt needn’t leave the economy.

That said, this grain of truth doesn’t eliminate the ocean of evidence against Krugman’s claim that worrying about the burden the national debt might impose on future generations is nonsensical. Here are some reasons why this argument is fundamentally flawed.

A large share of the national debt is owed to foreigners

For starters, it’s not the case that the national debt is entirely owed to “ourselves” (i.e., that it is exclusively owned by US citizens). Nearly one-third of the US debt ($6.636 trillion of the $22 trillion in debt) is owned by foreign governments and international investors.

This isn’t necessarily a bad thing. The willingness of foreigners to lend to the U.S. government has helped keep Treasury rates at historical lows, making it cheaper for future taxpayers to repay the interest on the national debt. If the US government is running deficits to finance justifiable initiatives (say, fighting World War II) and spending programs that will boost future growth, we should welcome funds from investors regardless of their nationality.

Nevertheless, it undercuts Krugman’s case that repaying the debt won’t burden future taxpayers and the future economy on net because the money will “stay in the U.S. economy.”

The fallacy of “we” and the reality that future taxpayers really do “foot the bill”

A bigger problem is that Krugman commits what Don Boudreaux calls the “Fallacy of Us, We, and Our.” Even if the entire national debt is owned by US citizens, there is no real sense in which “we” owe the debt to “ourselves.” The individuals incurring and benefitting from the debt are entirely different from the individuals who must bear the burden of repaying that debt.

Once we move past the intellectual sleight of hand of using collective pronouns like “we” and “ourselves” to describe all Americans across time, we get a much clearer picture of who gains and loses from the national debt.

Current taxpayers and citizens clearly benefit; they receive the benefit of increased government spending without incurring the full cost of those expenditures. Future taxpayers and citizens, who will have to repay the debt as it comes due, are clearly hurt. They have to pay higher taxes to repay the debt incurred and owned by the prior generation.

This insight remains true even if the older generation sells them its bonds before they pass. As James Buchanan astutely noted decades ago, future generations first have to buy these bonds from the prior generations. And, in order to buy them, they must first reduce their consumption. It is that reduced consumption — not the higher taxes they’ll have to pay when the debt is retired (since, by assumption, that money will flow right back to them as bondholders) — that is the true cost imposed on future generations from government debt.

Government debt “crowd outs” private investment and creates deadweight loss

The “we owe it to ourselves” argument also glosses over two of the most important arguments for why deficit spending is not a free lunch for taxpayers or the future economy.

First, deficit spending crowds out private investment. If the government increases the debt by $1 trillion to finance a large-scale infrastructure project, the $1 trillion it borrows from investors is money that could’ve presumably instead gone toward private investments. The increase in the demand for loanable funds sparked by this large-scale deficit spending will also cause interest rates to increase, thereby reducing private consumption and investment. Put another way: all the workers and capital that must be utilized for these projects must be bid away from other (often more productive) projects. All these “unseen costs” of deficit spending are worth highlighting.

To be fair, Krugman doesn’t deny that crowding out can occur. Instead, he argues that crowding out only applies when the economy is at full employment. If the economy is in a recession, crowding out won’t occur because the real resources employed in deficit-financed projects would have otherwise sat idle and, hence, aren’t being bid away from private-sector projects.

Even this more reasonable claim is controversial. Crowding out was still a problem during the Great Recession. The mere fact that there is underutilized labor and capital in the economy doesn’t mean deficit-spending projects can perfectly target those idle resources.

Lastly, the higher taxes required to pay off the debt create deadweight loss in the economy. We do not have access to a non-distortionary tax. Higher income taxes discourage work. Higher capital gains taxes discourage investment. Higher payroll taxes discourage hiring. And so forth. Hence, higher taxes — in any form — will discourage production, meaning some gains from trade will go unrealized.

Conclusion

The “we owe it to ourselves” argument certainly has a superficial appeal to it. Perhaps that is why it has lingered around as such a prominent argument ever since it overthrew the “old fiscal orthodoxy” during the Keynesian Revolution of the 1930s.

But, upon closer scrutiny, “we owe it to ourselves” is a convenient myth to get the government spending desired today while foisting the bill on future generations. Ironically, it has all the essential elements of what Krugman mockingly calls a “zombie idea.” It has been repeatedly killed by theory and evidence, and yet it continues to stagger around the economics profession searching for fresh brains to eat.

APPENDIX: Thought experiment

A quick numerical example should help illustrate this point. Suppose that the government today decided to spend $1 trillion on infrastructure paid for by issuing 30-year treasuries. Assume for simplicity that there are only two generations of Americans (older and younger), the bonds are bought only by Americans, the bonds pay 0% interest, and there is no inflation (obviously these assumptions are unrealistic, but bear with me). Now assume that 29 years later, the original bondholders who are entering retirement decide to sell their bonds to the younger generations for $1 trillion. The next year, the government finally pays off the bonds by raising taxes by $1 trillion on the younger generation (although they obviously aren’t too “young” now).

According to Krugman, younger generations aren’t hurt at all. After all, so long as they bought the bonds from the old generation, the $1 trillion they’ll have to pay in higher taxes when the debt is retired in year 30 is entirely offset by the $1 trillion they are paid as bondholders. Their taxes went up by $1 trillion, but so did their income. It’s a net wash.

But it’s not a wash. What Krugman neglects is that the young(er) generation had to reduce its consumption to pay $1 trillion for these bonds in year 29. Adding it all together, the younger generation paid $1 trillion in year 29 (a $1 trillion debit from their accounts), then paid an additional $1 trillion in higher taxes in year 30 (a $1 trillion debit from their accounts) before receiving the $1 trillion payoff from holding these bonds (a $1 trillion credit to their accounts).

Add it all together, and it’s clear that the younger generation bore a net $1 trillion burden to pay for the debt incurred by the older generation. This is no fundamentally different than if they had never been sold the bonds at all by the older generation. In that case, the intergenerational transfer would be even clearer: the younger generation would pay $1 trillion in higher taxes to directly finance the retiring of the older generation’s bonds.

All this shows that debt burdens don’t magically disappear when we pass them along to future generations. You can kick the proverbial can down the road, but the road has to eventually end somewhere. (Bob Murphy provides some other helpful numerical examples here and here).

It’s also worth noting the ethical problems associated with passing the bill to future generations. One could argue the original bondholders voluntarily sacrificed current consumption to buy these bonds. But it is clearly not the case that future generations voluntarily agreed to any part of this arrangement. Their taxes get raised to pay for debts incurred by their predecessors. This is not only unethical. It’s undemocratic, since future generations never had a chance to vote on the original spending. From an ethical and democratic standpoint, then, it’s better that higher spending be financed by higher taxes today as opposed to higher taxes tomorrow.

Short-term debt (within one generation):

Gen A: $1T debt. A buys $1T that pays off $2T in 10 years w 7% interest rate (benefit)

Gen B: $2T tax hike to pay off A for the bond (cost)

Long-term debt (across two generations)

Gen A: $1T debt. A buys $1T that pays off $2T in 100 years w 0.7% interest rate (benefit)

-ASSUME: At T = 50 years, A sells bond to B for $1.5T

Gen B: $2T tax hike to pay off debt at T = 100, which puts $2T in their pocket

NOTE: net result is not a harmless “wash” for Gen B. They gave up $1.5T at T = 50 to receive $2T at T = 100. BUT right before they get the $2T payoff they are taxed $2T. So they gave up $1.5T at T = 50 and received a net benefit at T = 100 of $0 ($2T payoff – $2T tax hike). So this cost them $2T in what they would’ve earned on this investment if not for the tax hike (or $1.5T depending on how you look at it).