It’s Time for a Taxpayer Debit Card

The coronavirus has revealed the U.S. Federal government’s inability to make timely payments to citizens. Most adult Americans were promised a $1,200 relief payment. But millions are still waiting for their paper checks. If the government is going to adopt a policy of providing direct relief to its citizens, the payments should at least be prompt. A $1,200 lifeline is less helpful if it arrives 75 days later.

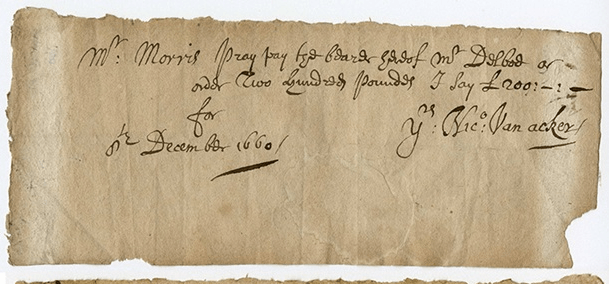

Much of this sluggishness can be blamed on paper checks. The good ol’ paper check was a remarkable payments innovation in its day. But it dates back to the 17th century. We’re better than that. In the early 1970s, the banking industry developed a technology for making fast, secure, and cheap digital payments: electronic fund transfer, or EFT.

Like most U.S. businesses and individuals, the Federal government has been taking advantage of this bit of 1970s technology. As of March 2018, 93% of all Federal payments were made via EFT, with the remainder being made by paper check. However, the snail’s pace of coronavirus relief illustrates the need for additional progress. An IRS debit card would be a step in the right direction.

On March 27, 2020 the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act was passed. Known as the CARES Act, it tasked the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) with sending all Americans who have an income below $75,000 a $1,200 stimulus payment.

No other Federal institution has as much information about citizens’ payment details than the IRS. It sent out 112 million tax refund payments in 2019, 92 million of which were deposited directly into a bank account. The remaining 20 million went via the mail as a check.

When the coronavirus hit, these 20 million check recipients faced a problem. The IRS only had their addresses, not their bank accounts. Unless they used the Get Your Payment tool to provide banking information, they would have to wait for a relief check to arrive by mail.

Checks are slow. The Treasury is only capable of printing up and sending around 5 million per month. Postal delays further clog up the system. The IRS has forecasted that the last relief checks wouldn’t be mailed out until September. And then, for those recipients among the millions of unbanked Americans, they will have to pay a check-cashing fee of $5 or more.

Checks are also costly for the government to process. According to a 2010 report by Financial Management Service, a bureau of the Treasury, it costs the US government just 10 cents to issue an electronic payment but $1.02 to issue and mail a paper check.

One step that the IRS has taken to help facilitate the $1,200 coronavirus relief payments is to distribute prepaid debit cards rather than checks. Beginning last week, around 4 million American households began to receive their Economic Impact Payment (EIP) Cards.

The EIP card is a partnership between the Federal government and Metabank, the financial institution that manages the program. Card holders do not have to pay a monthly fee, can make purchases and bill payments for free, and have the ability to withdraw cash for free at in-network ATMs.

Distributing EIP cards instead of checks should reduce the government’s costs of paying relief, speed up the payments pipeline, and provide Americans with a cheaper way of accessing funds than going to check cashing outlets.

As part of an overall strategy of promoting electronic government payments adoption, the IRS should consider making a government-sponsored debit card like the EIP Card a permanent part of its tax refund payments menu. It would speed up relief during future pandemics and disasters and reduce the IRS’s costs during the regular tax refund season.

There is certainly a precedent for accelerating the shift. In 2011, the Federal government mandated that anyone receiving Federal benefits such as Social Security and Supplemental Security Income must be paid electronically. Currently 99% of all Federal benefit payments have shifted to an electronic format.

Many benefit recipients don’t have a bank account. That is why the government offers them the option to receive a government-sponsored prepaid debit card. Around 5 million Americans have one of these Direct Express cards, which is currently issued in partnership with Comerica Bank.

If the Social Security Administration can go electronic, so can the IRS. But the IRS has a lot of catching up to do.

With 20 million out of 112 million tax refunds still being made by check, the IRS’s rate of electronic payments is a paltry 82%. Again, the Social Security Administration is at 99%. We know from studies by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation that around 94% of Americans have a bank account. Another 1-2% who don’t have a bank account do have a prepaid debit card, which can also receive direct deposits. So ~96% of Americans are capable of receiving an electronic refund payment from the IRS. But only 82% currently do so.

Even if everyone who can receive digital payments at present opts to do so, that still leaves 4% of Americans. An IRS debit card would fill this gap.

To speed up electronic payment adoption, the IRS could begin by updating its tax form to include the option to receive an IRS prepaid debit card as one of its refund choices, along with the traditional options of check or direct deposit to a bank account. A number of states already issue tax refunds via prepaid card, including New York and Georgia.

A more direct approach would be to mandate that all IRS tax refunds be paid electronically. Those with bank accounts could input their bank account information. The unbanked could ask to have a low-fee IRS prepaid debit card sent to their address.

Another option would be to offer all three options but encourage filers to switch to electronic payments by offering a reward, or levying a penalty. For instance, a processing fee of $1 could be added to anyone who wants their refund in the form of a paper check. The fee could be avoided by requesting direct deposit to a bank account or the mailing of a prepaid debit card.

Once filers have received an IRS debit card, they would be able to keep it for subsequent tax seasons, or as backup in the event of Federal emergency payments.

Interestingly, the U.S. Treasury ran a pilot debit card program for IRS tax refunds in 2011-12. The MyAccountCard pilot program offered roughly 800,000 pilot participants a prepaid card for electronic delivery of their federal tax refunds. These MyAccountCards could also be used for everyday financial transactions such as receiving paychecks by direct deposit, withdrawing cash, making purchases, paying bills, and building savings.

The MyAccountsCard study established that there was demand for an IRS debit card. In particular, it found the highest takeup rate to be among those most likely to be unbanked.

Speeding up the shift away from government checks should make future disaster payments proceed much faster. It would also improve the process of paying tax refunds by allowing both the Federal government and individual filers to avoid the cost and hassle of paper checks. An IRS debit card is one prong in the overall strategy of achieving 100% electronic payments. The EIP Card, the Direct Express Card, and the MyAccountCard pilot are all great examples of what this might look like.