Is it Proper for Men to Be Creative with Formal Wear?

There seems to be a fashion this season for new approaches to men’s formalwear, and I’ve been getting questions about it.

Is this proper or tacky? Exactly what are the limits here? Here is my answer.

This is probably the third round of such experimentation in my adult life. It’s as if people suddenly get bored with the traditional black tie, studded white shirt, black dinner jacket, and black trousers with a satin stripe. Hey, how come all the women at this party look amazing while every man looks the same and together the men look like they should be standing on an iceberg at the North Pole and have tiny unusable wings on their sides?

It’s a good question. The answer is as follows: the men all look the same precisely so that the women can stand out, dress up, be fancy, and display themselves in all glory. This is precisely how it is supposed to be. It’s the reverse of the animal kingdom where the male cardinal is fancy and the female is plain.

The evolutionary reason has to do with gender balance (and you are free to reject the following; don’t shoot the messenger). The explanation is that in general men have superior body strength and are hence more physically threatening by their nature and thus must affect a variety of displays of deliberate disempowerment to even out the balance in the interests of gender tranquility. This is why men open and hold doors, bow and defer, pay for meals, light cigarettes, and affect other forms of obsequious service as part of the rubric of social life. Deliberately declining to don fancy, glittery, overtly individualistic clothing at high-end socials is part of that protocol.

As with any of these rules, they only matter if they are operational in a world of prosperity and choice. If everyone is scratching around in dirt and living hand to mouth just to survive, high-end manners never become a reality to which anyone but the lord of the manner and his family must comply. The world in which manners and dressing protocols begin to matter is the second half of the 19th century.

This tradition in the modern world began in the aftermath of the Civil War at the dawn of the great enrichment in America, when the possibility of exercising clothing choice spread from the aristocratic upper classes to the newly capitalistic well-to-do. The question for men in this age in America was: how can we look amazing and keep to the protocols of what is right and not right?

In 1865, the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII) wore the black tie and dinner jacket (instead of the more formal cutaway coat) and this was borrowed for social occasions in Tuxedo Park, New York, which had become a fashionable area for hunting and fishing clubs for the newly rich. This is why the black tie and dinner jacket in America, and only in America, is called a Tuxedo.

According to the Wall Street Journal:

The story of how the tuxedo made its initial debut in American society dates back to the Gilded Age, when the founders of the posh Tuxedo Park resort in Orange County, N.Y., are thought to have introduced the coat at their exclusive sporting club. This fall (2011), current residents of the Park, along with the local historical society and the distinguished Savile Row clothier Henry Poole & Co. plan to celebrate the legacy of the tuxedo in a manner befitting its eminent birth.

The word has always been and remains a colloquialism. The proper term is black tie. Predictably, the tux disappeared mostly during world wars one and two – no one cares about such finery when the nation is involved in a seemingly existential struggle – but returns in times of peace and prosperity.

Now to the subject at hand. To what extent can traditional wear be adjusted and remain in the realm of propriety? In the 1960s, you began to see the jackets change with new seasonal plaids. In the 1980s, red ties became popular. And now we see the sudden emergence of what was considered tacky in the 1970s reinvented into a high-end product: the velvet dinner jacket.

The look is still formal but it steps out of the bounds of what is supposed to be the canonical social requirement that men dress more or less identically in order to make room for the women to shine.

My own view on this is that while duty seems to require that men decline to be fashionable at formal events, there are times when you just have to say: hey, this is boring!

What are those occasions? Every woman knows the difference between a cocktail dress and a formal long dress, and which occasion calls for what.

I would simply suggest that the same is true of men. The traditional garb can be adjusted for cocktail parties asking for black tie. It means you can wear a white, red, pink, or Polkadot tie. You can wear a plaid or velvet dinner jacket (not just any sport coat please).

On the other hand, for a formal ball – say a benefit ball for the opera or a foundation – play it safe with the traditional garb. Thus does it depend on the occasion.

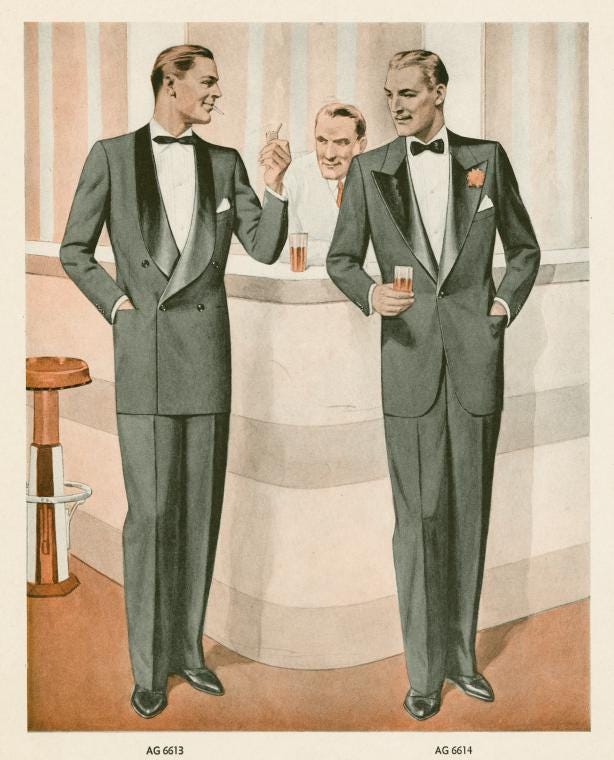

That said, there are ways to distinguish yourself even with the traditional tuxedo. You can wear a single high collar, a pocket square (white only please), double breasted, or a shawl collar. You can choose pearl shirt studs. There is an endless number of formal options for cufflinks and hence no requirement as such to stick to black.

A little bit of signature goes a long way here.

Keep in mind that there is a reason that all of this represents a modern tradition. Only modern capitalistic economies created a glorious opportunity for everyone to dress in the attire reserved for the royalty of old. We democratized formality, and there’s no better time to show precisely how this works than during the holiday season.

Women have long understood this. It’s time for men as well to step up and embrace both the rules and the proper way to break them.