Institutions Matter More than Climate Change

In the last weeks, the topic of Venice’s floods has been heavily discussed in the media. This is part because it has been argued by some that it represents a vivid illustration of the problem posed by climate change. As such, the occasion has been used to renew calls to actions to mitigate climate change.

However, in the midst of these conversations, the MOSE project was frequently mentioned. The MOSE project refers to an infrastructure plan that aimed to construct a high-tech floodgate system to deal with rising water levels. MOSE was inaugurated in 2003 and its completion was planned for 2011. The project is still unfinished as a result of several political scandals involving corrupt local officials. Its completion date is now set for 2022.

Because of the story of the MOSE project, I see a nuance that few have made either in the specific case of Venice or in the wider discussion about climate change mitigation and adaptation. That lesson is that “institutions matter” in determining the extent of the problem caused by climate change.

When one reads the literature on global warming that comes out of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), one will be able to find estimates of the projected costs of temperature changes on human welfare. There is a large range of changes in human welfare estimated but they all tend to agree that worldwide, the reduction in per capita GDP by 2100 will be around or below 10%.

However, when one breaks it down by region, one gets a different portrait. The majority of countries in the world would experience a decline in GDP per capita and a substantial portion of that majority would suffer income losses of more than 10%. Most of the areas affected are relatively poor countries.

Why would poor countries be more affected? Is it because they just happen to be poorly located? That could be it, but a more reasonable explanation is that poverty is vulnerability. All else being equal, richer individuals are less vulnerable to environmental shocks than poorer individuals. If one plots a graph of current income levels relative to projected income losses as a percentage of income, one will find a pattern whereby poor countries suffer larger losses than richer countries.

The extent of projected damages by climate change to human wellbeing is thus dependent on the poverty-induced vulnerability of millions of human beings. This is why some economists argue that “poverty reduction complements greenhouse gas emissions reductions as a means to reduce climate change impacts”.

And this brings us back to Venice. While it may seem like an odd parallel to draw, it all boils down to institutions. Reductions in global poverty levels are heavily contingent on institutions that respect the property rights of the poor, that encourage entrepreneurship and reduce the barriers to trade and exchange. Simultaneously, the institutions that improve the living standards of the poor will also make them less vulnerable to climate change.

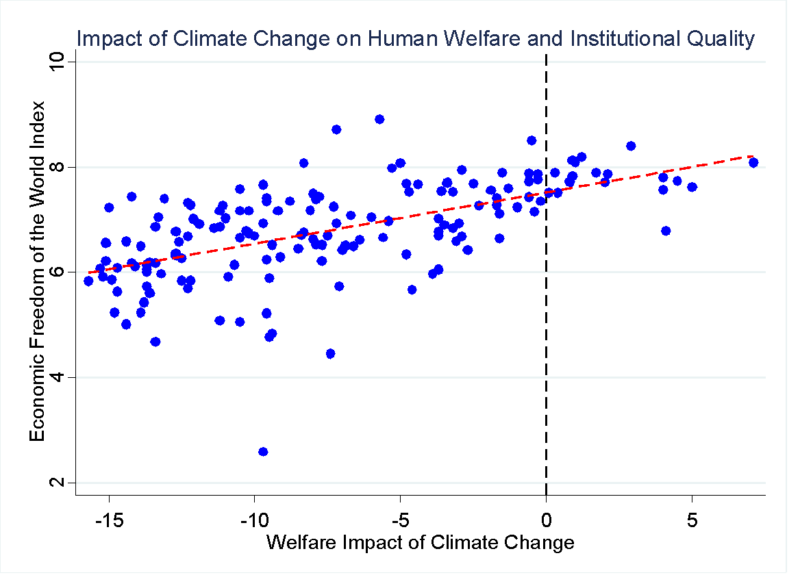

Thus, you ought to observe a positive relationship between institutional quality and the damages wrought by climate change. In the graph below, where institutional quality is proxied by the Economic Freedom of the World index data, this is one can observe. Countries with freer institutions (i.e. that respect property rights, limits entrepreneurial barriers and permit freer trade) stand to suffer less from climate change.

Venice stands as a microcosm of this lesson. The harm that the local population stands to suffer because of rising water levels could be mitigated by the MOSE project (some say fully mitigated). However, the project was plagued by recurrent delays occasioned by corruption scandals. The city’s mayor, along with 35 other individuals, was arrested in 2014 on corruption charges after siphoning millions of dollars from the project. Corruption is a well symptom of low institutional quality.

Notice the similarities between the global scale and the local scale. In both cases, institutional improvements would reduce vulnerability to climate change independent of policies that are aimed at reducing the level of greenhouse gases. This is a subtle but important nuance. At the heart of that statement is a concern with the welfare of humanity and the desire to bring the poor up. The cost of a climate change is a barrier to the fulfillment of this desire. The cost of climate, not the extent of temperature change, is the object of concern. If the costs are heavily determined by low-quality institutions, then the issue of institutional quality ought to be the object of our attention.