Inflation and Coronavirus Monetary Policies

Is there any reason to think that inflation might increase in the near future after the current coronavirus lockdowns and stay-at-home orders end? The Federal Reserve is engaging in extraordinary policies that will substantially increase excess reserves in the banking system. That said, the Fed did similar things during and after the Financial Crisis of 2007-2008 and inflation has been benign since. Are the current policies as likely to have little or no effect on inflation?

There are contrasting views by experts, among them Tim Congdon in an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal and George Selgin on the Alt-M blog. Congdon says that “history suggests the U.S. will soon see an inflation boom.” Selgin says that “[I]f denying any risk of future inflation is unwise, so is exaggerating that risk, or claiming that it’s imminent when it isn’t.” Selgin quotes Olivier Blanchard as saying that the risk of inflation is “very small.”

In fact there is reason to be concerned that Federal Reserve policies will not work out so well this time.

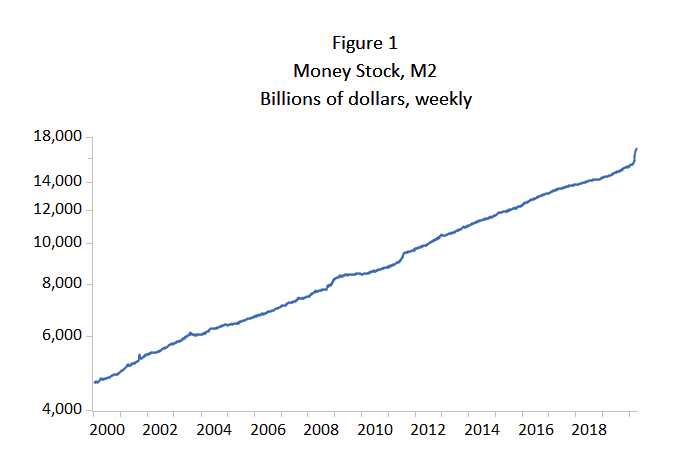

One way of assessing future inflation is the quantity of money in the United States. Figure 1 shows that the money stock, M2, has increased substantially, even relative to the increase during the Financial Crisis of 2007-2008. Inflation, which loosely speaking results from “too much money chasing too few goods,” can result from more rapid growth of the money stock.

Lockdowns and stay-at-home orders and other disruptions associated with the coronavirus pandemic have reduced employment and output substantially. The size of the decreases remains to be seen but filings for unemployment insurance by roughly 30 million people in the United States certainly suggest a very large decrease in goods and services to be purchased by this larger stock of money. This decrease in goods and services available is likely to be temporary though, so it is the increase in the money stock that is a longer-term concern.

Is recent money growth likely to continue? To the extent that the increase in M2 is associated with stimulus payments and unemployment payments, those sources of increases in M2 probably will not continue for more than a few months.

The Federal Reserve, though, is on track to increase its balance sheet and reserves in the banking system substantially by buying financial assets and making loans to private firms. Purchases of financial assets are little different than the Federal Reserve’s policy since the Financial Crisis of 2007-2008. What is there to worry about?

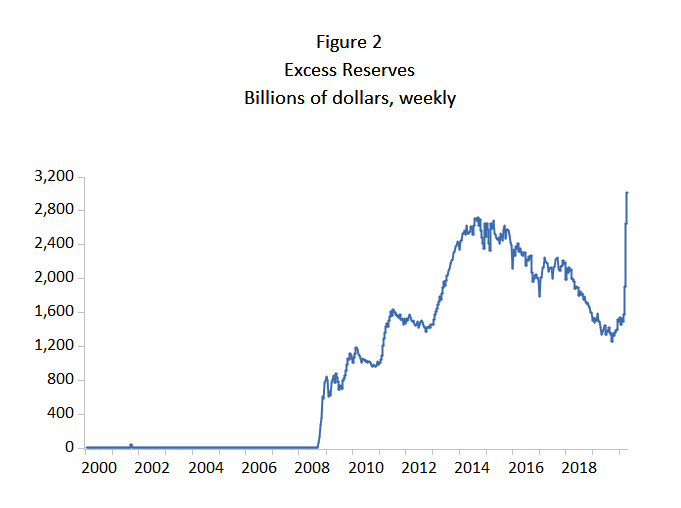

The Federal Reserve has been operating a system in which it pays banks to hold reserves over and above required reserves. The Federal Reserve has used those excess reserves, which are deposits at the Fed, to acquire assets, long-term Treasury securities and mortgage-backed securities. Figure 2 shows that excess reserves increased substantially during the Fed’s policy of quantitative easing (QE) implemented in QE1, QE2 and QE3 visible in the graph.

Current policy proposes to increase reserves and asset holdings substantially more in the near future. The size of that increase is not certain, but the Treasury has provided credit protection and equity investments of $235 billion in the financial vehicles acquiring assets and making loans. Excess reserves increased by 90 percent from March 3 to April 22. It would not be particularly surprising if excess reserves reached twice the prior peak of $2.7 trillion. They already exceeded that prior peak by over 10 percent on April 22 and surely will exceed it by 25 to 50 percent ultimately.

The outsize increase in the Fed’s balance sheet during and after the Financial Crisis of 2007-2008 quite obviously had little or no effect on the M2 or on inflation. Are there reasons to think that conditions now are different?

A major concern is that banks may not want to hold the additional reserves in excess of requirements. Why not? About a third of these excess reserves are held by U.S. branches of foreign banks. These reserves satisfy a recently added requirement for banks: the liquidity coverage ratio. Reserves at the European Central Bank (ECB) also satisfy this requirement but the Federal Reserve pays interest for holding reserves at the Fed while the ECB charges interest for holding reserves at the ECB.

There is foreign-exchange risk associated with holding dollars instead of euros, but that apparently does not deter foreign banks from holding liquidity at the Fed instead of the ECB. Large U.S. banks also are subject to the liquidity coverage ratio.

Is the demand for excess reserves unlimited? There is a major constraint on banks’ desire to hold excess reserves paying a relatively low interest rate. That constraint is a required leverage ratio imposed by banking regulations. The leverage ratio is a minimum requirement of equity capital in a bank relative to assets.

Expansion of assets by acquiring excess reserves eventually runs into the leverage ratio, at which point equity capital would have to be issued to satisfy the required leverage ratio and increase holdings of reserves. Given the cost of capital and the interest rate on excess reserves, any bank doing this would be reducing the value of the bank to shareholders. In short, banks will eventually stop adding excess reserves.

If a bank doesn’t want to hold an increase in its excess reserves, what can it do when its excess reserves increase? Instead of holding the excess reserves, the bank can loan the money out or buy a security after holding reserves equal to a fraction of its increase in customer deposits. Other banks would do the same. Through the traditional multiple expansion of deposits, the money stock would, unlike in recent years, increase because excess reserves are increasing. If the Fed does not reduce excess reserves, or increase the interest rate it pays on excess reserves, an increase in the money stock ensues.

Such an increase in M2 due to Fed policy would increase the dollar value of goods and services produced. Printing money does not increase production of goods and services for very long if ever. Increases in prices and inflation ensue.

The recent and prospective increases in excess reserves are different because the creation of excess reserves did not run into the leverage ratio. Without running into the leverage ratio, monetary policy from 2010 to 2020 could let the demand for money determine the quantity of money. With low expected inflation, the growth of money was consistent with that low expected inflation and in fact low inflation followed. If the Fed increases excess reserves and holds fast to those increases, inflation can result if banks no longer find it advantageous to hold those excess reserves.

How big is this risk? It is fair to say that no one knows. As recently as Spring 2019, the Fed was reducing excess reserves and found that banks wanted to hold a much higher level of excess reserves than expected. Similarly, the upper limit to how much excess reserves banks want to hold is uncertain.

Not knowing the relationship between monetary policy and inflation is a risky way to conduct monetary policy. Maybe everything will work out fine; maybe not.