In Praise of the Washington Metro’s Merchandise Experiment

Washington’s transit agency has a reputation for mismanagement, high costs, and often tone-deaf public relations attempts in their quest to cover for these failures. Riders are acutely aware of these deficiencies and are quick to react to signs of the agency taking steps to distract from its service cuts, fare increases, and persistent calls for new funding streams.

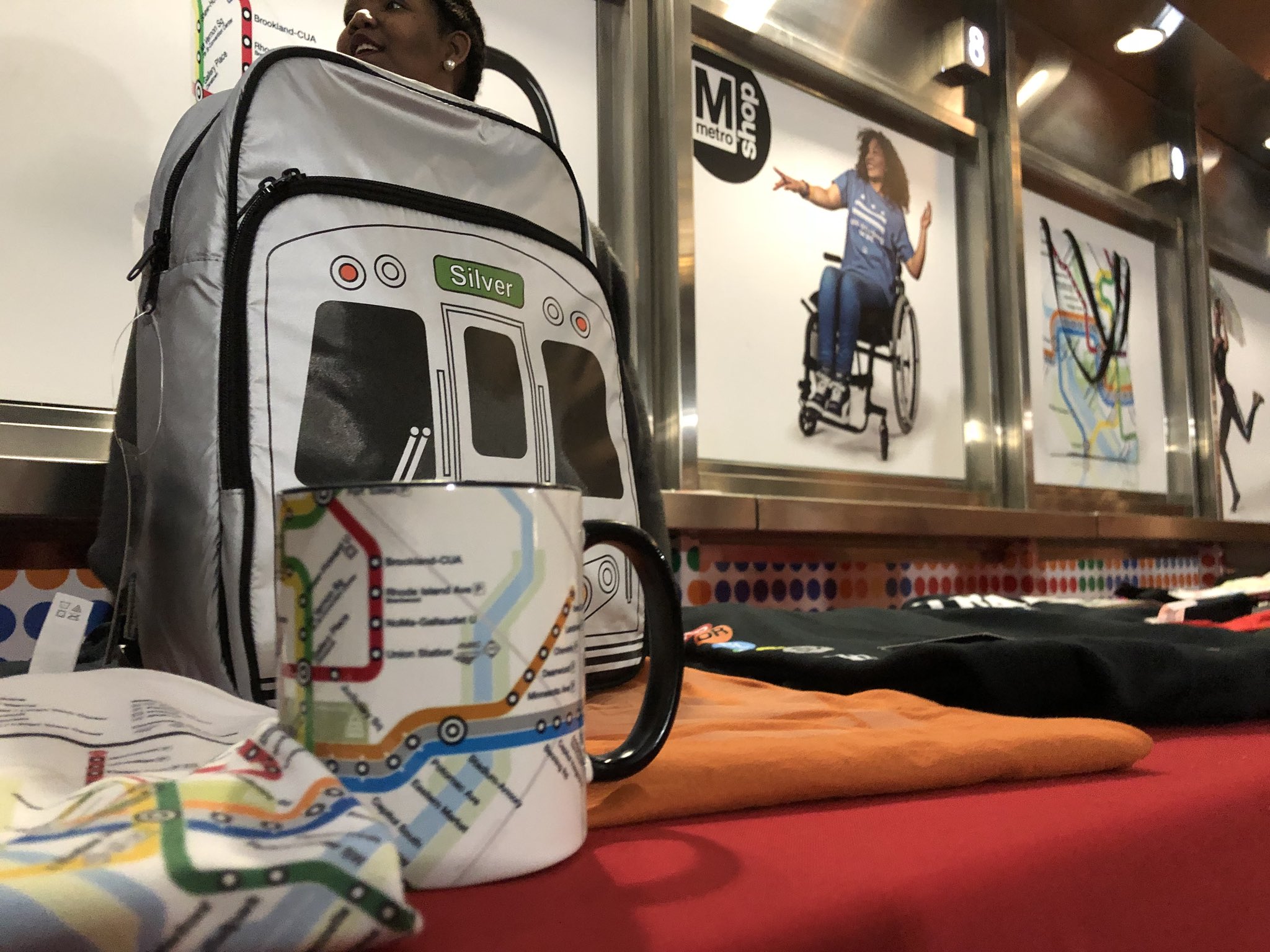

In recent weeks the trans-jurisdictional government body took flak for running a merchandise table at one of its subway stations. To many, the booth was another sign of a distracted agency more caught up in righting its image than running a world-class transit system. It was almost too perfect of an example for Washington’s myriad disaffected transit commentators. Others, such as Martin di Caro writing for Greater Greater Washington, thought the story was overblown, citing local critiques and those aimed at broader audiences.

Yet beyond the local news hype are stories of political economy, about entrepreneurship at public agencies and how it can bring public and private spaces together. Transit agencies are conservative, budget-maximizing bureaucracies. They have little incentive to take entrepreneurial action needed to bring any sort of change at all.

The time between trains is understood to be the dominant factor in how many people ride. This tests transit agencies’ core competency. They don’t need to be so conservative if they can allocate resources to maintain sub-10 minute wait times. In other words, well-run agencies have less to fear experimenting with ways to make the trips a little better, and poorly run agencies need internal entrepreneurship to become good enough to provide the frequent and reliable service riders demand.

In Metro’s case, they used under-worked staff from the network’s only manned sales office, and sold items already available from the agency’s website. Most agencies can find a a few dozen man-hours to spare for ad hoc plans.

At a minimum, this demonstrated that there was valuable space that could be rented to retail tenants on station mezzanines. These intermediate structures that connect train platforms and station entrances get the foot traffic retailers crave. Such spaces could also house information booths from the neighborhood business community or civic associations seeking to reach those who live or work in the community. In pioneering the use of its own space, Metro demonstrated some willingness to cede some of its space to the sale of goods.

Public-transportation agencies can follow their peers in the infrastructure community in finding new ways to incorporate private activity into public spaces. Metro does not need to look far for an example. Just outside its doors, in Amtrak-run Union Station, food court tables gave way to a Samsung store last Summer.

There two are ways to make the experience of riding transit better. A dominant quantity margin—wait time and reliability—as well as the secondary quality margin that embodies the things that can make a trip better regardless how long you wait. Adding even temporary retail to Metro platforms can mean umbrellas on wet days or hats on cold ones.

The agency took the initiative, tried something new at little cost, and laid out a space that could be used by others in the future, like a housing developer building a model home. This kind of initiative is uncommon at the agency, and should be praised, not derided as many have.