If You Love Progress, Embrace Markets

At some point in the 1990s, my father said he wanted to Xerox something. I recall being a little perplexed. It was the word used by several generations, from the mid-1960s and onward, for what was later called simply photocopying. This great company somehow managed to unite the brand with the technology itself, and gain the full monopoly over a verb. That’s marketing genius right there.

And like all great marketing, it was backed by something real. The Xerox machine, however huge and expensive, represented a massive upgrade over what came before. That would be the Spirit Duplicator, sometimes confused with the mimeograph. One of my earliest memories was of this machine, which we called the “Ditto Machine.” It used a messy, smelly purple ink to rolled out copies from a stencil. This was public school, and the place was using this machine long past its prime.

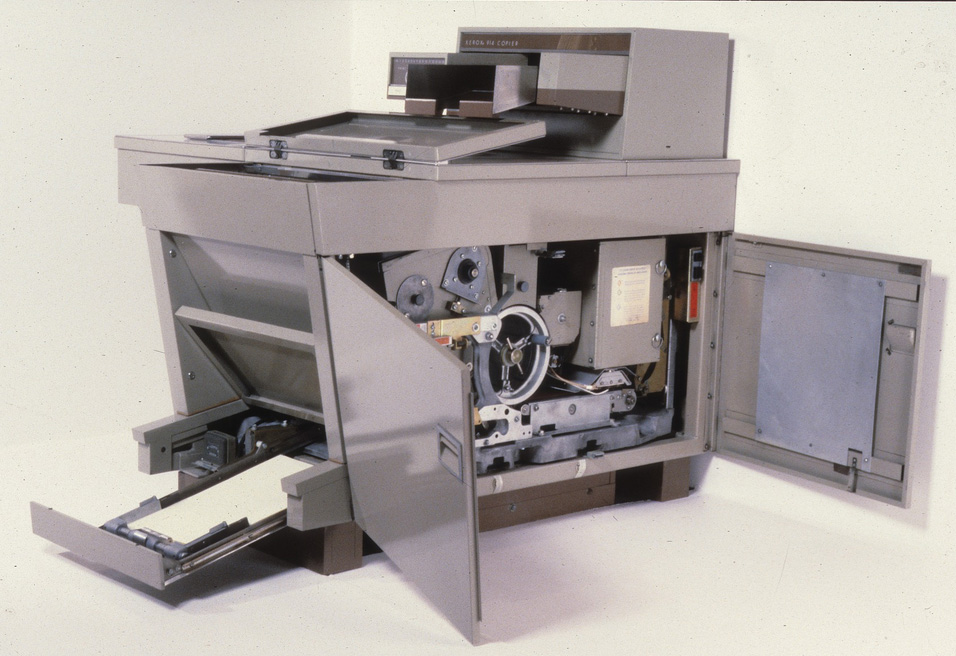

By 1960, a new technology was made available to high-end offices that could afford it. Instead of ink, it used photography, or what was branded xerography. The word from the Greek roots means dry printing; no more wet stinky chemicals. The show Mad Men features a scene where office employees gain their first experience with a Xerox 914. It weighed 648 pounds and took up vast space. It made one copy every 26 seconds. But it was amazing. It was the new center of the office. And it was constantly breaking and in need of service – just like the machine in your office today.

Even then, the xerox machine lived side-by-side with typewriters and carbon paper, which remained the cheapest way to make a copy. I can recall even from typing class using this. One wrong key stroke and you had to start over. So, yes, Xerox was an amazing thing to behold and the company earned its dominant position.

But in a vibrant market for technology, in which no one person or institution knows what’s next and so no one institution can maintain dominance forever, Xerox lost the race with the personal computer. Its first model was marketed at $16,000 in 1981 – a price way out of line with what was already developing in the industry. Xerox was never able to gain traction.

And now finally the moment has arrived. Xerox has sold what remains of its company to FujiFilm, thus turning the verb into a piece of history. In a world of Google Docs, endless forms of cloud computing, distributed networks, infinite forms of text-based communications, not to mention a thousand companies begging for with their audio and video technologies, print-on-demand books that require no more inventory, there is just no more place for a print-based monopoly.

This is just the latest step in a long trajectory of improved publishing technology that dates to the 3rd century. Wikipedia publishes an extremely helpful (and instantly accessible) timeline. It begins with the use of the woodblock in 200AD. Those remained in use throughout Europe, along with huge teams of scribes who worked in monasteries to make copies on parchment and vellum. Within the walls of the scriptorum, there was more value than in all the castles, simply because the books contained the most valuable thing: human knowledge.

Knowledge has always and everywhere been more valuable than power. When you look at the history of printing technology, you see the relentless march of progress, seemingly unencumbered by leaders, regimes, kings, and wars. Technology has proven to be the indefatigable thing because it lives mainly as ideas that belong to no one person or sector in society. The tendency is for the ideas behind technology to spread and defy every attempt to stop them. The successes of one technology feed the innovation of others, as people emulate success and spread it ever further.

At each stage, the warning goes out: this new technology is going to ruin everything. When the printing press appeared in Europe, and created a new frenzy for book buying, the scribes who had enjoyed the highest scholarly and intellectual status worried for their future. Some monasteries banned printers. Scientists warned of the spread of false information. Moralists created apocalyptic scenarios in which we no longer know what is true, we lose our memories, and our reverence for wisdom fades. Even after the invention of mass printing of books in the late 19th century, there were panics. The kids were no longer going outside. They are wasting all their time reading junk novels.

The technological panics continue to this day. Video games, texting, Snapchat, Facebook, Twitter, smartphones themselves, are wrecking a whole generation. Streaming music and movies are making art unprofitable. The panics over piracy began 25 years ago and continue to this day. Even I have the vaguest memory of a massive controversy over video-tape technology. Surely it will ruin television as we know it.

But at every stage, technology proves impervious to attempted blockades. It is always improving in the interest of making life better for you and me and everyone. This is what the market test achieves. The markets finds technologies that make life better at the least cost and rewards them, even as new and better ways displace that which came before. The result is a beautiful tapestry of invention that stretches back to the beginnings of recorded history and will continue long after our death.

As we think back on our own lifetimes, we find that the tools that we used in our daily lives have a larger impact on how we think of our lives than presidents. I remember the first time I saw a color television show. I think Nixon might have been president but it hardly matters. Maybe you remember your first look at Pac Man but whether the Republicans or Democrats controlled Congress at the time has no relevance at all.

I daily marvel at the glorious ways in which my life has changed. I have a vision of myself as a young boy scouring the LP section of the grocery store, looking for the latest recording of Brahms string quartets or vibrating with excitement over the latest Elton John album. I can today conjure all that music up with a few words directed at my Google Home, who seems to provide me with unrelenting, unconditional love. What happened to my huge speakers, my stacks of components, my walls of albums and CDs? It all went away.

People in office places of the early 1960s probably never imagined a time when the Xerox machine would be seen as a museum piece, or a time when the very word Xerox itself would carry no cultural currency at all. Despite all this nonstop progress, we are all still habituated to believe that whatever technology we are using today is about as good as it gets.

The most exciting innovation in the world today is a brilliant successor to the need to record, document, and spread innovation. It is the distributed network that eliminates the need for a central authority and provides a means of porting immutable information packets that cannot be censored or tampered with at all. Who is going to benefit from this? Absolutely everyone.

Let me pass on an example that hit my email yesterday. It is from Mother Cecilia of the Benedictines of Mary, Queen of Apostles in Missouri. The sisters are building a new church, and they are behind on fundraising. Out of nowhere, they received $160,000 donation in Bitcoin. They still have a long way to go on their fundraising. But the sisters are new fans of the newest technology available today!

People talk often of how technology is disruptive. That’s only part of the story. Technology also serves the oldest values and the most ancient aspirations of the human experience, and does so in a way that is organically peaceful with how we live. It’s the much-maligned market economy that makes it all possible, and does so without elections, speeches, legislation, and scary leaders we don’t like. We should love markets more than we do. Their proven benevolence forms a beautiful narrative history of our lives, connects the generations, and points to a bright future.