How LockDowns Shattered the Structure of Production

Old fallacies have a way of reappearing, especially, during times of social and economic crises. The current coronavirus crisis has opened the door to a variety of them, including the notion of a “paradox of thrift.” It is the idea that if people save more of their incomes by reducing their consumption expenditures, they will lower the market demand for final goods and services, thereby reducing earned profit margins, and thus eliminate the incentive for that greater savings to be borrowed for investment purposes, which will put a drag on employment opportunities. It is a fundamentally flawed notion.

This argument was recently made following the May 29, 2020 announcement by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) that in April of this year, the personal savings rate of Americans had shot up to 33 percent of disposable income, after being about 13.7 percent in March. At the same time, due to greatly increased government spending on a variety of anti-coronavirus programs, personal disposable income increased by $2.13 trillion or 12.9 percent, while personal consumption expenditures (PEC) decreased by $1.89 trillion, or 13.6 percent.

The fall in consumer buying and the rise in unspent income (savings) was and has been due to the government mandatory shutdowns of production and work, and the radical restrictions on retail shopping to what has been classified as “essential” purchases (food, medicines, etc.). These prohibitions and restraints are only now being lifted by state governments around the country at different times and to different degrees.

The Fear That Less Consumption Means Fewer Jobs

While a number of economic analysts have argued that as the economy is increasingly opened up and people are freer to go back to work and purchase things that they had been prevented from buying by political decrees during these last three months, consumer spending will likely return to pre-coronavirus levels, with accompanying lower rates of personal savings out of income.

But others expressed the concern that if people end up changing their spending and saving habits to some extent away from consumer demand purchases, the more permanent shift toward savings may dampen the needed consumption expenditures to once more make it lucrative to bring back into employment many of those who have been laid off or let go.

After all, as it is usually pointed out, consumption expenditures make up about two-thirds of total spending in the economy. In 2019, U.S. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) came to a bit more than $21.4 trillion, out of which consumption expenditures made up a bit more than $14.5 trillion, or almost 68 percent of the value of all output produced in the economy last year. New private sector investment spending came in at around $3.8 trillion of GDP in 2019, or around 18 percent of the American economy.

Therefore, surely any significant decline in consumer spending threatens a greater impact on the general economic well-being of the country as a whole, it is claimed. At the end of the first quarter (January-March) of 2020, the BEA reported that preliminary data suggest that GDP was $21.5 trillion. With a decline in consumer spending of almost $2 trillion in April of 2020 ($1.89 trillion), this would represent over a 9 percent decline in GDP as the latter stood at the end of March.

Gross Output in Austrian Economics

However, there is a wider and more inclusive measurement and estimate of the total value of the economy as a whole, known as Gross Output (GO). It includes not only the market value of all finished goods and services and new net investment, but the total value of all intermediary stages in the production processes in the economy.

That is, GO includes the business-to-business expenditures in the supply-chains of productions in progress through time, more closely capturing the market value of economy-wide gross investment that is required to maintain the outputs of goods and services period-after-period.

While most economists would generally accept that virtually all production takes time, and that any given production process invariably passes through a number of “stages” of investment activity to be brought to its final, finished form as available goods for purchase and use by the ultimate consumer, it has been the “Austrian” economists who have tended to give the most attention to the time structure of production in explaining the interconnected and interdependent processes of a complex market economy.

This has been the case since the founding of the Austrian School of Economics by Carl Menger (1840-1921) in his Principles of Economics (1871), in which he highlighted and emphasized the causal and complementary relationships between the “higher” stages of production of the means of production (resources, labor, and capital), in intermediary stages of production through which any good passes before being completed into its finished and useable form.

One of his early intellectual proteges, Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk (1851-1914), extended and elaborated on this time-connected nature of the creation and use of capital, and its relationship to the valuation of time from which originates market rates of interest in his grand works, Capital and Interest (1884) and The Positive Theory of Capital (1889).

Menger and Böhm-Bawerk’s writings on capital and interest soon were taken up by others including Frank W. Taussig (1859-1940), in Wages and Capital (1896) and especially by Knut Wicksell (1851-1926), in Interest and Prices (1898) and Lectures on Political Economy (1901;1906).

It became an essential element in the Austrian theory of the business cycle, particularly developed by Ludwig von Mises (1881-1973), in The Theory of Money and Credit (1912; 2nd ed., 1924), Monetary Stabilization and Cyclical Policy (1928), and in Human Action: A Treatise on Economics (1949; 3rd ed., 1966); and by Friedrich A. Hayek (1899-1992) in, Monetary Theory and the Trade Cycle (1929), Prices and Production (1932; 2nd ed., 1935), Profits, Interest, and Investment (1939), and The Pure Theory of Capital (1941).

In the immediate decades after the Second World War, when the Austrian School was in hiatus during the long period of Keynesian domination, the theory was kept alive by Ludwig M. Lachman (1906-1990), in Capital and Its Structure (1956), by Murray N. Rothbard (1926-1995), in Man, Economy, and State (1962), and by Israel M. Kirzner (1930- ), in An Essay on Capital (1966).

With the revival of the Austrian School following Hayek’s winning of the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1974, the Austrian theory of capital was restated and extended by a new generation of “Austrian” economists, in particular, Mark Skousen, The Structure of Production (1990), Peter Lewin, Capital in Disequilibrium (1999), Steven Horwitz, Microfoundations and Macroeconomics (2000), and Roger W. Garrison, Time and Money: The Macroeconomics of Capital Structure (2001), to just mention the ones that have had the most influence over the last twenty years.

Time-Structure of Production Leading to a Consumer Good

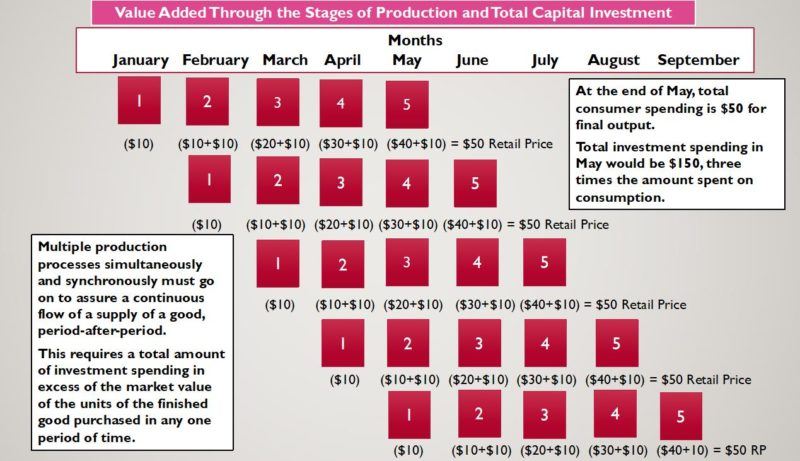

Figure 1

Some essential qualities of “Austrian” capital theory are, perhaps, better understood in the context of the example offered in Figure 1, above. Suppose that there is a production process leading to a final, finished consumer good that requires five stages of production for its completion, with each of these stages taking one month. Let us imagine that a particular good is anticipated to be wanted by consumers in May of some year. For this good to be ready and available for sale at that time, it will be necessary for the production process leading to its availability to begin in January of that same year.

For simplicity, let us say that each of the respective production stages requires $10 of additional labor, resource, and capital costs. Thus, in January, when this production process begins, $10 of inputs will be purchased and applied. At the end of January, the unfinished product will pass on to another manufacturing participant in the process who will pay the stage 1 enterprise $10 for its partly completed product and invest an additional $10 of invested inputs, which it then passes on to another manufacturing enterprise in stage 3 of this process for $20.

This latter enterprise, in turn, adds $10 more of inputs in bringing the product one step closer to completion, at which point he sells the, still, unfinished product to the manufacturer in stage 4, who pays $30 to the preceding producer and adds $10 more. At the end of April, the product is passed on to the last of the complementary producers in this manufacturing division of labor, who adds one more $10 of inputs to finish the product into its final form and to, then, sell it to interested consumers for the anticipated and actualized price of $50 that incorporates the value-added of each of the five stages of production.

Complementary Investments Through Time for Continuous Output

When the concept of Gross Domestic Product is explained to students, it is said that only the value of the final finished product, the $50 at which this good has been sold, is counted in GDP, because to add in the input expenses of each of the earlier stages of production would be “double-counting,” that is, adding in some of the expenses in the manufacture of the good that is already included in its final price, that $50, which reflects the values added at each of the five stages of production.

If production was one time, and if there were no other productions not yet completed simultaneously going on, this would often be a reasonable rule to follow. But when attempting to evaluate and estimate the value of all the economic activity going on, at any moment in time and over any given period of time, to calculate the value of all continuous economic activity, the GDP rule, by itself, leaves out an understanding of the nature and workings of the interconnected economic processes as a whole.

Let us look at Figure 1, again. If the same good is wanted by consumers not only in May but in June of this year, as well, then given its five-month manufacturing stages of production, in February, stage 1 of this good’s production process has to begin, while the good to be ready for sale at the end of May is in its stage 2 of production.

If the good is, likewise, to be wanted also in July, then in March when May’s consumer good is in stage 3 and June’s good is in stage 2, July’s ready to buy and use good will have to be starting its stage 1. And let us suppose the same is true for all future months as private enterprisers are looking ahead in deciding what to produce and when to try to have it available for sale.

If we look at May of this year, at the end of that month, the good whose manufacture began in January is ready to be sold for its total $50 value-added.

At the same time the good to be ready in June will have at the end of May total value-added expenses of $40 ($30+$10); for the good that will be ready in July, at the end of May it has had cost expenditures of $30 ($20=$10); for the good planned for August, its in-progress cost expenditures at the end of May will be $20 ($10+$10); for the good to be marketed to consumers in September, at the end of May it will have had its first $10 expenditures for its stage 1.

Thus, at the end of May there will be $50 of GDP consumer good-related expenditures. But at the same time, in May there will have been total investment expenditures of that $50+$40+30+20+10. The dollar value of Gross Output expenditures will have totaled $150, or three times the value of the market value of the final consumer goods sold at the end of May.

Gross Output and Supply-Chains During the Coronavirus

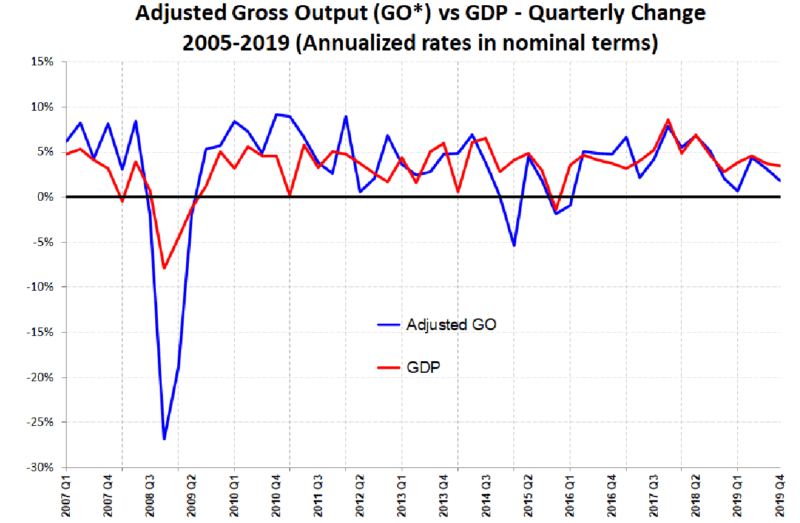

While the Bureau of Economic Activity estimated, as we saw, that GDP at the end of 2019 was around $21.4 trillion, the BEA also calculated that GO was about $38.2 trillion, or almost twice as large as standard GDP. While final quarter GDP for 2019 grew at about 2 percent over the previous quarter, GO only grew by around 1.1 percent in the fourth quarter of last year.

Thus, business-to-business spending was slowing down as 2020 was beginning even before the government shutdowns brought numerous sectors and industries to a halt or reduced working levels in the face of the coronavirus.

Chart 1

Due to many goods already in-process and inventories and the continued availability of various needed inputs, few goods “disappeared” from retail store shelves from March to May 2020 when the lockdowns and shutdowns were most extensively in effect. The exceptions, for the most part, were the sudden and unexpected far greater demands for medical-related goods due to the coronavirus which was exacerbated by government restrictions on alternative market-created supplies; and consumer panic-buying out of fear of future shortages of “essential” paper products and antiviral cleaning supplies.

There is little doubt, however, that if the shutdowns and lockdowns had continued fully unabated for another month or two, well into the summer, the breaks in the supply-chains of goods in the stages of production would have resulted in really reduced supplies of a growing number of consumer-demanded goods. With the goods in the “higher” stages of the respective production processes drying up, once the restrictions and prohibitions were lifted it would have taken longer to bring many of those consumer goods back on to the market, since it would have been necessary for many of these goods to pass through their entire manufacturing stages before being available again at the retail levels.

Market Coordination of the Time-Structures of Production

All of this brings out that total or gross investment is the largest component in value terms of ongoing economic activity in the market, and not the value of the finished goods sold at the end of that hypothetical month of May, in the example that was given. Behind the total dollar value of GO is a complex, interconnected and interdependent network of microeconomic divisions of labor in each line of production and across different lines of production, all simultaneously occurring, and all needing to be effectively integrated and coordinated in time and through time to assure balanced allocation and use of all the raw materials, component parts, capital equipment and skilled and experienced labor services to assure that everything necessary is being done at the right time, in the right place, with the right inputs, given their respective opportunity costs in alternative uses.

Appreciation of these intricate time-structures of production and their interrelationships is part of the reason that the Austrian economists have also emphasized the nature, working, and irreplaceability of the market-generated and market-guiding competitive price system. The multitudes of people participating in these vast numbers of separate but interconnected time-structured stages of production that incorporate not only the actions but the global locations of the workforces of the entire world can be harmonized in no other way than through the ever-changing prices for everything, everywhere that capture any twists and turns in any and all shifts in market supply and demand.

What is crucial, therefore, to the effective and successful workings of an economy, in terms of output, employment, and standards of living is the investment sectors of the economy. There is no consumption without production, there can be no effective demanding of what others may have produced and are offering for sale without reciprocal supplying and selling to earn the means to buy what others can supply to us. (See my article, “There Will be No Recovery Without Production”.)

Böhm-Bawerk’s Reply to the “Paradox of Savings”

Rightly understood, savings need never be a hindrance or dissuader to investment and production. The type of thinking expressed in the notion of the “paradox of savings” is that if people stop demanding as many consumer goods as they have been buying in the recent past, because they decide to save more, the falling off in consumer demand reduces the revenues and profits of those bringing consumer goods to market.

With reduced profits for such goods, the incentives for businessmen to take up any additional savings available on the market though investment borrowing may be greatly diminished. Consumer production is cut back, workers in these sectors of the economy are let go, and without alternative private-sector spending to take up the slack through investment borrowing, alternative employment opportunities fail to appear, thus leaving the economy with rising and maybe permanent unemployment – unless government deficit spending makes up the difference and creates jobs with borrowed or created money.

An answer to this type of reasoning was offered well over a century ago by that Austrian economist, Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk. At the beginning of the 20th century, an economist named L.G. Bostedo argued that since it is market demand that is the stimulus for manufacturers to produce and bring goods to the market, a decision by income-earners to save more and consume less destroys the very incentive for undertaking new capital projects that greater savings is supposed to facilitate. Bostedo concluded that greater savings, rather than being an engine for increased investment, served to retard investment and capital formation.

In 1901, in an article entitled “The Function of Savings,” Böhm-Bawerk replied to this criticism. First, he said, economists had long explained that as long as there is as yet unsatisfied and unfulfilled wants there would always be more work to be done, and therefore the employments to be filled. The type and the location of the work to be done may change with changing patterns of demand, but there is always work for willing hands at market-based wages.

But what Böhm-Bawerk considered to be the central weakness in Bostedo’s argument was a crucial word that he left out of his presentation. “There is lacking from one of his premises a single but very important word,” Böhm-Bawerk said. “Mr. Bostedo assumes … that savings signifies necessarily a curtailment in the demand for consumption goods.” But, Böhm-Bawerk continued,

“Here he has omitted the little word ‘present.’ The man who saves curtails his demand for present goods but by no means his desire for pleasure-affording goods generally…. For the principle motive of those who save is precisely to provide for their own futures or for the futures of their heirs. This means nothing else than that they wish to secure and make certain their command over the means to the satisfaction of their future needs, that is over consumption goods in a future time. In other words, those who save curtail their demand for consumption goods in the present merely to increase proportionally their demand for consumption goods in the future.”

But even if there is a potential future demand for consumer goods, how shall entrepreneurs know what type of capital investments to undertake and what types of greater quantities of goods to plan to offer on the market in preparation for that higher future consumer demand?

Böhm-Bawerk’s reply was to point out that production is always forward-looking – a process of applying productive means today with a plan to have finished consumer goods for sale tomorrow. The very purpose of entrepreneurial competitiveness is to constantly test the market, so as to better anticipate and correct for existing and changing patterns of consumer demand. Competition is the market method through which supplies are brought into balance with consumer demands. And if errors are made, the resulting losses or smaller-than-anticipated profits act as the stimuli for appropriate adjustments in production and reallocations of labor and resources among alternative lines of production.

When left free, Böhm-Bawerk argued, the market successfully assures that demands are tending to equal supply and that the time horizons of investments match the available savings needed to maintain the society’s existing and expanding structure of capital in the long run.

“Paradoxical” Savings Today the Result of Government Shutdowns

If it seems, today, that savings is running to waste in the face of decreased consumer spending and curtailed business borrowing and investment, this cannot be placed at the door of “capitalism” or “market failure.” It has been governments that have commanded the stoppages to production and work, that have controlled when, how and for what consumers may spend the money and incomes they have on desired goods otherwise purchasable on the market.

It is those governments that have delayed or staggered the timing and capacity of private enterprises – small, medium, and large – from opening their doors, bringing production fully back on line, and creating the opportunities for people to once again participate in supply-side productions and sales to restore their income-earning capabilities to demand more of the goods that lockdowns and shopping restrictions have prevented them from taking advantage of.

There is no “paradox” to increased savings and its underutilization for investment and employment purposes, when governments have barred the doors to the factory entrance and the shopkeeper’s counter.

Freeing markets from government commands and controls will get goods fully flowing again through the stages of the time-structures of production, along with re-establishing the jobs to get all the work done. Fully lifting government restrictions and restraints will see people, once again, willingly demanding all the goods they want when they are at liberty to freely work and earn, to supply and demand, once more.