How does monetary policy affect resource allocation?

If monetary policy had no effect on economic performance, there would be no point in having any particular monetary policy in effect. This is the same as admitting that, at least in the short-run, monetary policy does in fact affect resource allocation. How this happens is a delicate and discussed issue in economics. If resource allocation depends on relative prices, then monetary policy should have an effect on relative prices to affect resource allocation. This is sometimes referred to as a Cantillon Effect, a term used to denote the fact that because some economic agents receive newly printed money before others some prices rise before others and therefore there are relative price modifications.

While I do not dispute Cantillon Effects, there is another “non-neutral” effect which rarely receives the attention it deserves. And this is the effect on present values when monetary policy changes the discount rates used in the market by investors. When economists think of prices in the context of models, the prices are usually timeless (or just spot prices.) That’s what we teach students when we go from perfect competition models to monopoly and all in between. More basically, think of a demand and supply chart where prices are defined. Prices, being the core of the economic analysis, become something devoid of its time element; inviting confusion when we move forward to more complex scenarios. However, prices do not reflect the “price of a good.” Past prices reflect the ratio of exchanges that have taken place at particular times and places. Two similar apples traded at the same price in different places-times are still two prices even if they are for the same good. On the other side, future prices are expected transaction results.

Investment decisions depend on the present values discounted at the opportunity cost of expected future prices. This means that even if there are no Cantillon Effects and the expected future prices remain the same, the present value of projects that have different time horizons will still be affected differently. In other words, there can be a change in relative prices between goods A and B, pA/pB, but also a change in the relative present value of projects A and B, PV(A)/PV(B) without a change in pA/pB. This result follows from the fact that a change in market interest rates is a change in the relative price of time with respect to price of goods and services (think of the Wicksell Effect.)

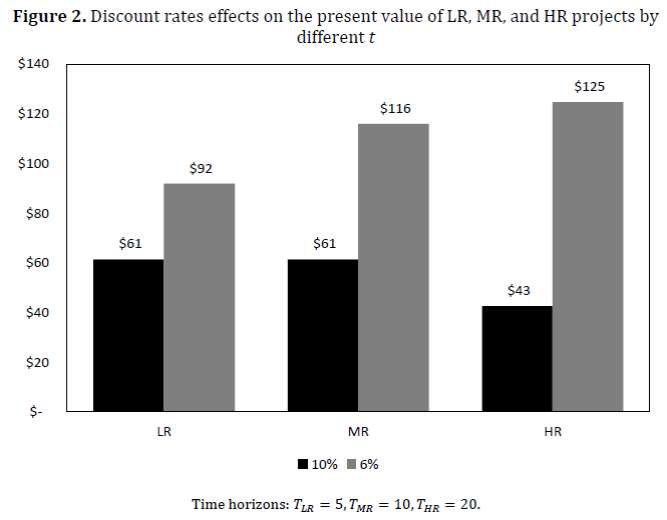

Consider the scenario depicted in the following chart taken from this draft (p. 16). There’s an initial moment denoted by the bars in black. Each bar shows the present value of three different projects, where LR stands for short-term, MR for medium-term, and HR for long-term. The grey bars denote the effects on the present value of each project when there is a policy that reduces the discount rate used by investors.

Sure, if discount rate falls, all present values increase, but they do so at different rates. In financial terms, the longer the project, the higher the modified duration of the associated cash-flow, which is the semi-elasticity of the present value to the discount rate. Simply put, the present values of different investment projects have different sensitivities to changes in interest rates. Ever since Keynes, in macroeconomics the focus is usually put on the relative price of all final goods (the price level) with respect to wages (price of labor.) But even in models that assume wage flexibility such that W/P remains unchanged, the relative present value of potential projects may differ to the point where the ranking of those projects is modified as can be seen in the figure, where the HR project goes from having less market value to being the more valuable one. And as long as we believe relative prices have an effect on resource allocation, then we should expect a policy that affects discount rates to have an effect on the economy as well. To assume that wages are flexible does solve neither the problem of resources allocation or business cycles. The assumption that relative present values do not change is also needed.

With a different approach, Young finds similar results when observing the easy monetary policy of the U.S. after 2002. He finds (1) that what would be the HR industries increase their value added more than relative less forward looking industries and (2) a look at the data appendix of the article shows that the ranking of these industries do in fact change in some cases.

There are two side implications of this. First, to deny that there are Cantillon Effects (or that it is economically relevant) does not mean there is no resource misallocation. Second, Cantillon Effects are not necessary to make an argument for credit-based theories of the business cycle like the Mises-Hayek or Austrian business cycle theory.

Investors do not make decisions as described in microeconomic models or by macro aggregates that lack time valuation. Investment decisions are forward-looking, and therefore are decided based on the present value of expected cash-flows. With or without inflation, with or without changes in W/P, a credit expansion policy that affects discount rates used in the market is likely to produce resource misallocation. The question is not, or should not be, so much how monetary policy affects economic aggregates, but how it actually affects investors decisions in the market.

What is money neutrality?

A short clarification on what is understood as money neutrality. In my impression not always clear. One interpretation is that money neutrality does not affect relative prices (Cantillon Effects.) But only a few would probably dispute this for the short-run. Money neutrality, more precisely, means that in the long run changes in the quantity of money have no effect on the real economy. In the long-run relative prices are independent of the quantity of money and therefore the equilibrium is the same once the effects of a change in the quantity of money have faded-away. This, however, requires the assumption that the short-run effects of changes in the quantity of money have no effect on the determinants of equilibrium (preferences, endowments, etc.). Why should that be the case? If there is a change in preferences or loss of resources then the final equilibrium will differ with or without the change in money supply. In other words, money neutrality is an assumption, not a fact.