Facebook and Google Must Answer to the Market

Giant technology companies like Facebook and Google get that way because their size is a crucial part of their value. Facebook’s network effects and Google’s search algorithm, finely tuned by its own big data, are a large part of what makes the companies dominant in their respective markets.

But size also gives tech giants tremendous power that, just like that of big government, not only can but will be abused. 2018 saw Facebook and Google embroiled in seemingly endless scandals and controversies about what they do with their enormous caches of data.

The standard antitrust approach would consider breaking the companies up, but that would greatly reduce the value their component parts bring to the market. Seemingly less draconian measures would likely devolve into a complex web of rules that might even serve as barriers to entry to potential competitors down the road.

Can the market provide sufficient discipline to prevent future abuses by giants like Facebook and Google? Those who favor less antitrust enforcement often point to consumers voting with their feet or dollars as both more potent and less intrusive. Consider this a test.

Voting With Their Feet

For our purposes, “market discipline” means a firm either losing market share because of perceived abuses of power, or being preempted from bad actions by the credible threat of losing market share. Consumers may take their business elsewhere because the bad actions directly impact the value they receive (such as a higher risk of one’s own data being compromised) or because they don’t like the firm’s broader impact on society (such as spreading “fake news”).

In theory, perceptions of a firm’s impact on society are a disciplining force in every market. If I found out the chef at my favorite restaurant was a prominent neo-Nazi, I would stop going. But the most successful firms always have some wiggle room because of the superiority of their product or costs of switching away from it.

Market discipline doesn’t happen overnight — consumers first have to be alerted to the firm’s negative actions. In the case of Facebook and Google, we see this messy yet effective process unfolding in different ways.

Friend or Foe?

2018 might be remembered as the year when most consumers realized they were paying for their favorite online services. We spent two decades handing over our personal data to companies like Facebook and Google without bothering ourselves too much about what they were doing with that data or how much power they had gained as gatekeepers of news and other information. That dam broke in early 2018 with revelations about Russian agents spreading “fake news” on Facebook and the means by which some of those agents had obtained proprietary data consumers had provided.

With the media’s microscope fixed on Facebook, a year-long conversation about the site’s role in our lives ensued. We can put consumers’ concerns into two broad buckets: direct privacy issues about how Facebook collects and holds data, and the power Facebook has to be a gatekeeper of information given that data and its enormous market share.

The distrust the scandals engendered appears to have cost Facebook customers. Its share of the social media market dropped from 76 percent in December 2017 to 66 percent in December 2018. Though difficult to establish direct cause and effect, this dramatic drop certainly reflects the public’s heightened questioning of Facebook’s practices.

Facebook’s exposure to market discipline became even clearer this month when Mark Zuckerberg announced a dramatic shift in the company’s focus from public communication to private and encrypted sharing between groups of friends. The move amounts to the firm essentially leaving a market where it still has a two-thirds share, and multiple high-level executives who disagreed left the firm. In other words, this is not a move one takes lightly.

Revelations about Facebook’s use and misuse of data were exposed the company to serious market discipline. The immediate loss of customers coupled with the overall public perception apparently signaled to Zuckerberg that Facebook’s wildly successful business model would not be viable going forward.

Okay, Be a Little Evil

Google’s management appears to still be deciding how much market discipline they’re facing after a litany of revelations similar to albeit less severe than those at Facebook. The company has faced multiple recent data-related controversies such as the news last July that third-party Android app developers had accessed data from users’ Gmail accounts.

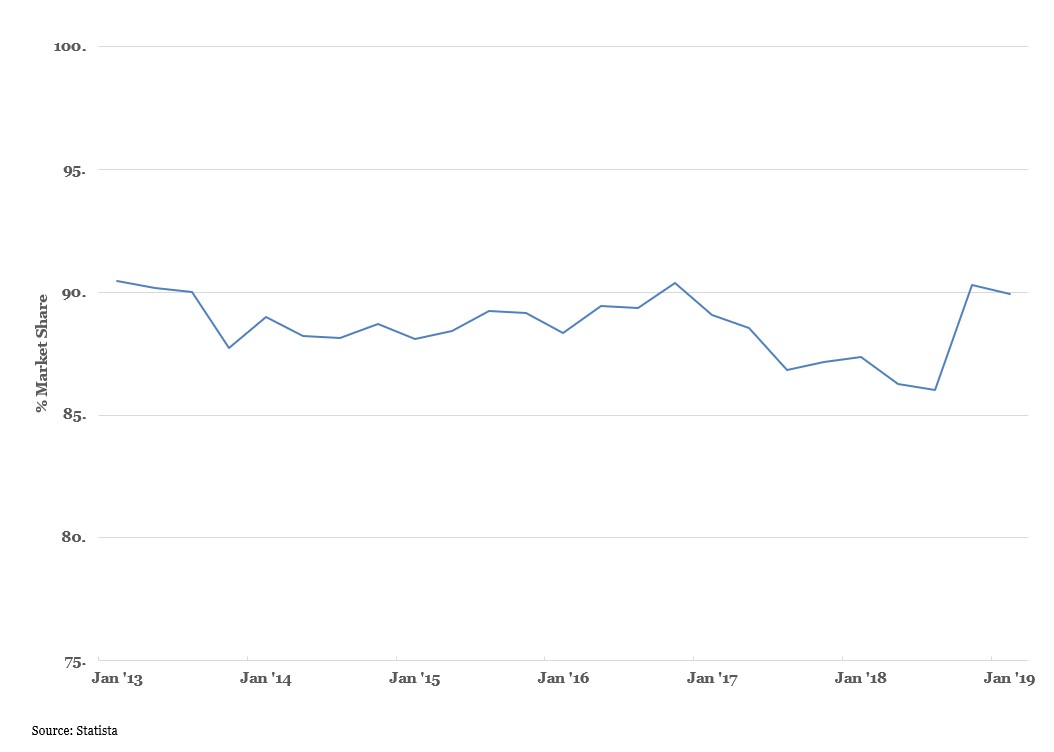

Google’s share of the search market presents a murkier picture of if and how dissatisfied customers voted with their feet. The chart below tracks Google’s share of the search market since 2013. Though always dominant, Google’s market share reached a low of 86 percent in October 2018, consistent with new consumer concerns, though the reasons for the pronounced rebound since then are not obvious.

Google’s share of the online search market, January 2013–January 2018

Google’s seemingly insurmountable competitive advantage stems in part from the data it collects every time we search. We know that Google’s search algorithm uses the data to better refine future results, though the company remains coy about its importance relative to other factors. Voluminous proprietary data is certainly one explanation for why nobody has ever been able to construct a search algorithm quite as effective.

If Facebook is a case of market discipline immediately and dramatically affecting a company’s decisions, Google shows the process operating at a slower and smaller scale. CEO Sundar Pichai avoided government discipline in December when his testimony to Congress was seen by many as evasive. In the current climate of distrust facing tech companies, the market will continue to constrain Google, but don’t expect a Zuckerberg-style change in business model anytime soon.

Watching Carefully

Market discipline is not a perfect process, but we see evidence of its effectiveness as Facebook begins a dramatic pivot, and many controversies threaten to constrain Google’s growth. This process can and should continue to play an important role, as standard antitrust measures would threaten to strip both of assets such as size that bring real value to consumers.

Americans seemingly love the scrappy entrepreneur but are inherently distrustful of the big, established corporation. Tech companies are often viewed heroically during their rise to prominence, but hit a public relations wall once comfortably established (Amazon, another tech giant, also faced multiple PR debacles in 2018). This instinct to distrust large companies can do economic damage, especially when combined with politics, but it also serves an important role in driving market discipline. Facebook and Google’s ability to watch their customers has made many uncomfortable, but after 2018 both know that their customers are watching back.