Does Government Spending Contribute to the Economy?

When governments spend more money than they bring in, they create budget deficits. When deficits accumulate as time goes by, governments incur debt. The U.S. federal government debt as of today is about $19.3 trillion, which, to put it in perspective, equals about 105 percent of the previous 12-month GDP.

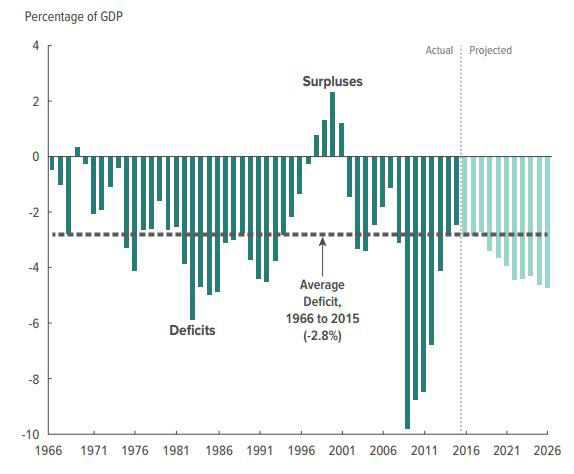

From 1966 to 2015, an average deficit of 2.8 percent of GDP was added to the national debt each year, according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). The CBO also projects the deficit would increase from 2.9 percent to 4.9 percent of GDP over the next decade if current laws generally remained unchanged.

Chart 1: Total Deficits and Surpluses in the U.S. during 1966-2016

Source: Congressional Budget Office

While most people are concerned about high government deficits, some argue governments should always be in debt and that government deficits contribute to economic growth. Their arguments are twofold: 1. Government deficits contribute to GDP, because government deficits must equal some non-government organizations’ surpluses according to the rule of accounting, and; 2.The federal government cannot possibly go bankrupt due to its debt, since the central bank can always create money to finance the government.

The arguments sound good only if we don’t consider the consequences. High government deficits and debt come with a cost. First, when the central bank creates money to finance the budget deficit, the economy gets exposed to risks of inflation. For now, about $2.4 trillion created by the Federal Reserve through its quantitative easing programs are sitting in the banking system as excess reserves. But it is a huge amount of money, about 19 percent of the current money supply, measured by M2, ($2.4 trillion excess reserves/$12.6 trillion money supply). If all this liquidity was loaned out, and all else holds equal, there would be 19 percent inflation immediately.

Second, if the government borrows from the public, such as individuals and corporations, it is crowding out private business investment. For instance, in 2015, the federal government spent 16 percent of its outlays on the military. In contrast, only one percent of the government spending went to science. If instead this capital was available for private business investments, as would be the case without enormous government borrowing, the market would likely allocate resources in a more efficient way.

Third, when the government borrows from the public, it drives up interest rates, which makes financing more expensive for businesses. An investment project that would be profitable with two percent interest rate would fall apart if the interest rate was five percent. As interest rates go up, private investment tends to fall, thus slowing the rate of capital formation in the economy, which in turn restrains economic growth.

All in all, government spending may be an effective stimulus during an economic recession when abundant liquidity is available. But over the long run, high government debt or deficits are costly to overall economic growth.

Click here to sign up for the Daily Economy weekly digest!