Do New York Times Headline Writers Believe Their Headlines?

Café Phillip is a sandwich shop on the NE side of K Street in Washington, D.C. Call this the historically unfashionable K Street versus K Street NW where the major lobbying shops have historically located. Until March of 2020, Café Phillip was booming. Staffed with energetic and highly professional immigrant employees, it did huge business in a part of D.C. that was increasingly filling up with office workers and residents.

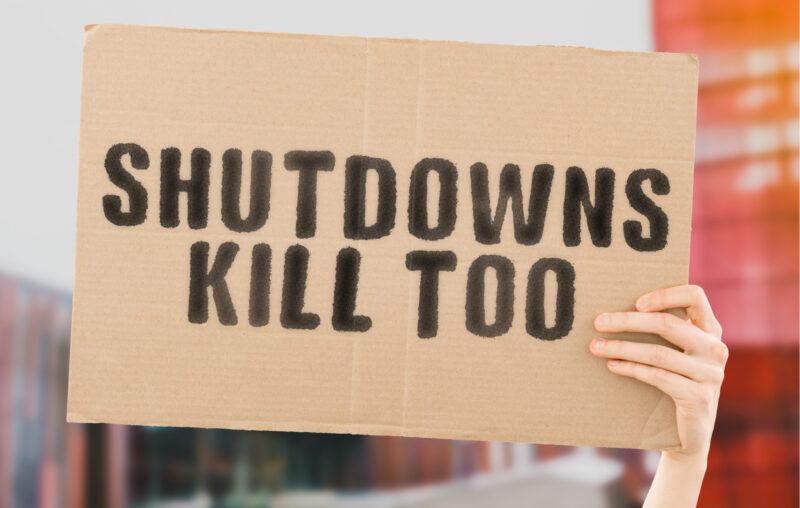

Then came the political panic related to the coronavirus. Even though there were no indications from the virus’s origin, or Asia more broadly, that it was terribly lethal, U.S. politicians panicked. In their panic they quite literally chose to fight the virus with strict lockdowns that resulted in soaring unemployment, bankruptcy, and economic desperation. It would be hard to imagine a more wrongheaded approach to a health threat. Think about it.

Economic growth has historically produced the resources for scientists and doctors that have made victories over viruses possible. Yet in their panic, politicians on the local, state and national levels forced the very contraction that would logically shrink economic resources, only to follow up with the extraction of trillions from the private economy in order to throw money at the horrendous problems they created. You really, really can’t make this up.

If Washington, D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser can sleep at night, it’s a miracle. Café Phillip is instructive in this regard. What was formerly packed, what was formerly defined by frenzied sandwich making in keeping with its enormous popularity, is generally empty during the day. Café Phillip is still open, at least for now. Other businesses in the area are beginning to close. Panicked politicians who will never miss a meal or a paycheck decided we the people couldn’t be trusted to go to work. We might spread the virus. Lockdowns were instituted, supposedly for our own good.

Sorry, but economic growth is what’s for our own good. It doesn’t just produce resources for those eager to find cures for viruses that make us ill or kill us, economic growth also frees us to quarantine or shelter-in-place if we feel some kind of virus threatens us. Please think about this. While many had the choice to work from home amid this panic, their options would have been great deal more limited in 2000. In 1980, forget about it.

Back to Café Phillip, to walk in nowadays is to see formerly energized employees with forlorn looks on their faces, mostly immobile as they wait for customers. It’s a far cry from what it used to be. And these are the employees that the Café still employs. The staff is a fraction of its former self, and it’s not unreasonable to speculate that if D.C.’s strict rules with regard to restaurants and offices continue, the Café will shut down.

It’s all a sickening reminder of how quickly politicians can wreck things. How they can thoughtlessly break things. They’re way too powerful on all levels.

Worse is that they’re breaking things in response to a virus that is once again not very lethal. What was obvious in the early part of 2020 when deaths didn’t soar in China is still obvious now.

To put a number to all this, the New York Times has reported all summer that over 40% of U.S. coronavirus deaths took place in nursing homes. The people dying with the virus tend to be very old, and with some kind of pre-existing malady or maladies. Who knows what the actual numbers are, but it’s no reach to conclude that of the 200,000 reported deaths related to the coronavirus, some (or maybe a lot) were on the verge of death either way.

To the above, some will respond that the musings are those of a heartless person. No, they’re not. In truth, they’re the words of a realist.

As this is being written, the global death count from the virus is a million people, but it should once again be at least suggested that the number is inflated. To die with something isn’t necessarily to die of it.

Still, for the purposes of this piece, let’s assume it’s a million. Better yet, let’s assume two million since the virus was traveling around the world for months before anyone was really testing.

The deaths are of course sad, but the same New York Times reporting that over 40% of U.S. virus deaths have happened in nursing homes has also projected that over 285 million of the world’s inhabitants are rushing toward starvation. Yes, you read that right. The Times won’t say it directly, but the panicked political reaction to the virus that revealed itself in contraction-inducing lockdowns and other limits on activity has parts of the world’s economy collapsing, and as a consequence hundreds of millions rushing back into poverty, starvation and death. Poverty is easily the biggest killer man has ever known. Nothing else comes close.

This would ideally get more attention from the Times. Consider the newspaper’s above-the-fold headline from Monday: “A Nation’s Anguish As Deaths Near 200,000.” Really? One senses the headline writers don’t even believe this. When old people die it’s sad, and sometimes very sad. But it’s rarely – if ever – a tragedy. Figure that death from old age is a very modern concept born of healthcare advances made possible by the very economic growth that politicians mindlessly snuffed out in their panic.

Thinking about anguish, the true anguish is born of hundreds of millions rushing back to poverty, starvation and death thanks to politicians fighting a virus with forced contraction. After that, a successful business is a bit of a miracle too. Most don’t make it, but when they do they lift up owners, employees and customers alike. Tragic is seeing what improves people, gives dignity to workers, and wealth to owners being snuffed out by politicians who will once again never miss a meal.

The New York Times might think about this as it publishes alarmist headlines that obscure actual truths reported within the paper. It’s sad when we lose our grandparents and old people more broadly, but it’s tragic to read of people starving, and heart-wrenching to contemplate formerly productive workers sitting, waiting for customers; increasingly aware that what puts a roof over their heads will no longer. Proportion New York Times, proportion.

Reprinted from Forbes