Digital Currencies and US Dollar Dominance

Since the Great Financial Crisis in 2008, cryptocurrencies have come of age. The advent of Bitcoin in 2009 is often thought to have been the beginning of cryptocurrencies, but as early as 1983, American Cryptographer David Chaum had invented the blinding formula, an extension of the RSA algorithm which is still used today for web encryption. Chaum went on to create DigiCash in 1989.

The backbone of modern cryptocurrencies is distributed ledger technology (DLT), which developed out of the public key infrastructure of the early 1990’s. There are numerous reasons why it took so long for cryptocurrencies to gain traction, but the financial crisis of 2008 was undoubtedly a catalyst. It was a crisis of trust; trust in the banking system, trust in the honesty of public institutions, trust in the value of fiat money itself. In the aftermath of the crisis, gold, along with other stores of value, rose in price, but Bitcoin, endowed with anonymity and a finite money supply, captured the imagination of a new generation of investors for whom gold was a technologically barbarous relic.

Of course, the anonymity of a public ledger also led to Bitcoin – and other cryptocurrencies – being used by criminals seeking to hide the proceeds of their illicit activities from the authorities. In the early days of Bitcoin adoption, many commentators anticipated that the authorities would outlaw its use, driving it underground. Perhaps because of its structure and the global nature of the internet, the authorities chose not to act in haste. Instead they observed and learned.

Today regulators and their governments are starting to prosecute crypto-criminals. Despite the anonymity of encryption, cryptocurrency seizures are on the rise, but at the same time central banks are preparing to launch their own digital currencies.

It is the implications of this development that I want to investigate in this article. To understand the motivation for the introduction of central bank digital currency (CBDC) one needs to look first at the evolution of the current fiat money system.

Prior to WWI the majority of developed nations linked their currencies to the price of gold. This was the era of the original Gold Standard. During the Great War the countries of Europe abandoned the Gold Standard and debased their currencies in order to finance the war to end all wars. The US benefited economically, selling goods to the allies who in turn made payment in gold or government debt. At the outbreak of WWI, Sterling had been the preeminent reserve currency; by 1918 the US Dollar had assumed preeminence.

During the interwar years, the US continued to supply goods to Europe. With the outbreak of WWII the flow of gold to the US accelerated to such an extent that the US acquired the vast majority of the world’s gold reserves. A return to the Gold Standard, after hostilities ended in 1945, was simply impractical.

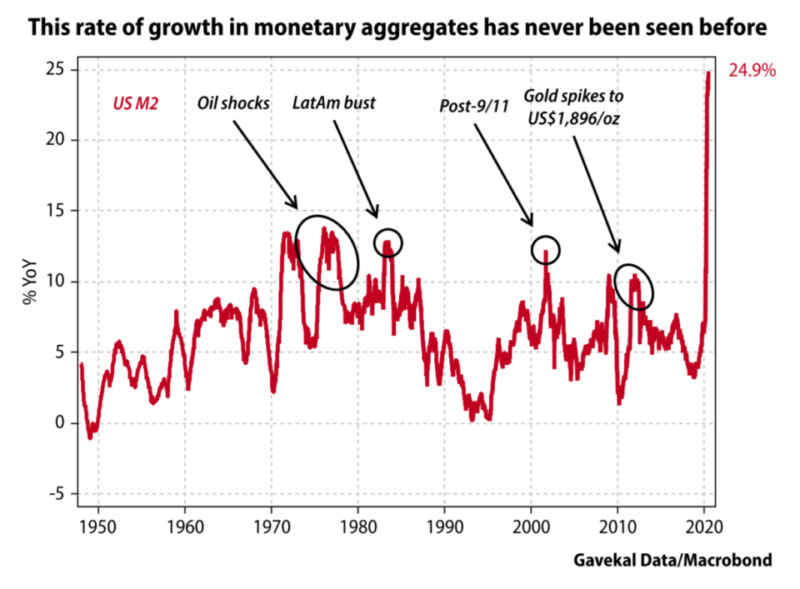

The year 1944 saw a meeting at Bretton Woods, New York, which led, with the ending of the war, to the introduction of the Gold Exchange Standard. Under this system gold reserves were replaced by US Dollar reserves. The Gold Exchange Standard, in its turn, collapsed in 1971, ushering in the era of fiat currencies, backed by the tax-raising capacity of each nation. Nonetheless, today more than 60% of all foreign bank reserves are still held in US Dollar cash or US Treasury securities. The Dollar remains the world’s reserve currency, but the recent pandemic has weakened its allure as a store of value, in part because the US government, abetted by its central bank, has expanded the monetary base to combat the combined supply and demand shock to the US economy.

Of course, this rapid expansion of the monetary base has had multiple side effects. In their semi-annual, report to Congress, published this month and entitled, Macroeconomic and Foreign Exchange Policies of Major Trading Partners of the United States, the US Treasury states: –

Over the four quarters through June 2020, a number of economies have experienced significant expansions in their current account surpluses, including China, Taiwan, and Vietnam, while other countries, including Germany and Switzerland, have maintained large trade and current account surpluses, which allowed for external asset stock positions to widen further.

Not content with an improved current account position with the US, a number of countries have doubled down, following the US lead as they race to debase their own fiat currencies. For most nations, however, what French Finance Minister Valery Giscard d’Estaing described in 1969 as the ‘exorbitant privilege’ bestowed upon the nation whose currency enjoys reserve status, means there is always enthusiasm for a viable alternative to the US Dollar.

Since the Great Financial Crisis, central bank gold reserves have risen rapidly. The chart below shows the main countries which have sought to diversify away from the US Dollar: –

China, the world’s second largest economy, has seen its foreign exchange reserves increase again during the last year. The composition of those reserves is not frequently disclosed but in 2019 the Chinese State Administration of Foreign Exchange announced that as at the end of 2014, US Dollar assets accounted for only 58% of their reserves, down from 79% in 2005. Since October 2016, when the Chinese Renminbi (RMB) became a constituent, the Chinese have volubly favoured the adoption of the IMF Special Drawing Right (XDR) – a statement of account rather than a tradable currency – as an alternative to simply holding US Dollars. Having been incorporated in the XDR, China anticipated that the RMB would quickly see its secondary reserve currency status grow, but as of April of this year, official reserves of RMB amounted to a mere $221bln, less than 2% of total central bank reserves. For China, their inability to promote the RMB as an alternative to the US$ has perhaps prompted other initiatives.

One such initiative is the introduction of digital currency electronic payment (DCEP), China’s name for their CBDC. The Chinese economy is well-positioned for such an innovation, as applications such as Alipay or WeChat Pay, together with the near ubiquity of the smartphone throughout China, means that digital payment is preferred to cash – in 2018 83% of payments were made through mobile devices. That figure is estimated to have reached 93% today.

The DCEP trial, launched in April, has been taking place in the cities of Shenzhen, Suzhou, Chengdu, and Xiong’an. It is cheaper and easier to use (and issue) than physical money and gives the authorities much greater control, both domestically and abroad. Every transaction can be audited, tax avoidance will be far more difficult and exchange controls can be more effectively enforced. If, during a crisis, the banking system should cease to function, the central bank could even deliver cash (or credit) directly to individuals.

The new currency does not come without risks to the incumbent system. For the individual, holding cash, securely in digital form, obviates the need for banks as deposit holders. If the banks have no deposits, their ability to lend is dramatically curtailed.

The international financial system could also be transformed. A digital RMB could eventually allow payment to sanction-bound countries without it having to pass through the dollar-based international payments systems.

At the beginning of December, Russia announced that a Digital Ruble will be introduced next year. The exact specifications are yet to be declared, but state control of the medium of exchange seems to be central to the endeavour. It has yet to be decided whether the Digital Ruble will be made available through the current banking system or provided directly to individuals. Russian bankers remain nervous!

Interest in CBDC is more widespread than just China and Russia. A survey published earlier this year by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) found that 53 out of 66 central banks were considering digital currencies. The BIS Markets Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures published a working paper on the subject in March 2018, simply entitled Central bank digital currencies. Among their observations was the question of, design choice; should its access be wide or restricted, wholesale or general purpose; the degree of anonymity; operational availability (24/7 or less); and whether or not to make it interest bearing.

The authors went on to look at the role of central banks, noting that in the current fiat currency marketplace they tend to restrict access to digital money whilst making physical cash widely available. They then discussed the benefits of DLT for the settlement of wholesale CBDC transactions, highlighting the capacity constraints and questioning DLT’s supposed technological advantage – much has changed since 2018 in that regard.

Since the use of physical cash was already in decline even in 2018, the BIS went on to consider the benefit of CBDCs as a means of bypassing the banking system and delivering money directly to the general public. Their enthusiasm was qualified and they asked whether there might be better means of achieving such goals, especially when fast and efficient private, retail payment products were already available. The authors recognised that digital money could (especially in a crisis) circulate even faster than traditional electronic cash, requiring central banks to react more quickly to rapidly changing demand for a broader range of eligible ‘good collateral’ assets. This again raised the issue of the disintermediation of the commercial banking system. Why should one bother having a checking account with a limited liability bank when you could avail yourself of the services of a friendly neighbourhood central bank?

The BIS then considered the benefits of nonanonymous CBDCs, allowing for digital records and traces, which would improve the application of rules aimed at anti-money laundering. Then, in stark contrast, they peered into the abyss, contemplating anonymous general purpose CBDCs, which could be a near and present danger, especially since these currencies would not be limited to retail payments and might become widely used globally, not just for nefarious transactions, but as a form of economic warfare. Economic sanctions against rogue states, for example, would be rendered entirely toothless.

Finally the authors’ opined on the need to monitor the development in digital technology and payments, noting the emergence of private digital tokens which would be neither the liability of any individual or institution and backed by no nation, nor any corporate authority. Their unspoken concern was of a challenge to the current order should the price of these private tokens become less volatile and investor protection improve. A common means of payment, which is both a stable store of value and a transparent unit of account could pose a real threat to the dominance of all fiat currencies. For the present Stablecoins, linked to the value of fiat currencies, fulfil this function, but with companies, such as Facebook, proposing to introduce their own currencies, an alternative means of exchange could quickly emerge.

Bringing the CBDC discussion up to date, the IMF – Glaciers of Global Finance: The Currency Composition of Central Banks’ Reserve Holdings published this month, discusses the change in the pace of digital transformation, the shortening of global supply chains – which reduces the need for the world’s principal reserve currencies. They focus also on the increased issuance of domestic currency denominated government debt by emerging economies. All these factors combine to reduce international reliance on the US Dollar, Euro, Yen and Sterling – to list the four most traded reserve currencies. The recently signed Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, a free trade agreement between Australia, Brunei, Cambodia, China, Indonesia, Japan, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, New Zealand, the Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, Thailand, and Vietnam, can only serve to further diminish demand for US Dollars as a medium of exchange.

The IMF authors conclude: –

There is currently no sign of major shifts in the composition of central bank reserve currencies. However, the glacial pace of change over recent decades should not be taken as an indication of the future.

The risk of an evolutionary leap forward to a multipolar world without a natural reserve currency may be closer than many commentators think. In November 2019, the Belfer Center, Economic Diplomacy Initiative, suggested the following scenario in Digital Currency Wars – A National Security Crisis Simulation: –

In the not-so-distant future, China becomes the first major economy to issue a central bank digital currency (CBDC). The development goes largely unnoticed at first, since payments in China are already highly digitized. Then, North Korea tests a nuclear missile that demonstrates significant advancements in its nuclear program. Analysts believe it could land a nuclear weapon in the continental United States within a year. These capabilities, it turns out, are funded using the Chinese digital currency, which U.S. authorities cannot track. Soon thereafter, countries that want to escape U.S. oversight and sanctions, like Russia and Iran, begin issuing their own digital currencies.

As the world watches the Chinese experiment with its DCEP, which is planned to be rolled out across China in time for the Winter Olympics in February 2022, the Digital Currency market looks set to bifurcate into state-sponsored currencies which give their issuers greater control and private coins, backed by no authority – although some will have an underlying intrinsic asset value. There will also be, as of now, anonymous and non-anonymous offerings, both from private and public issuers. A US CBDC is inevitable, if the US government does not want to be left behind.

Is this the end for the US Dollar as the world’s reserve currency? As Churchill might have said, ‘…This is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end, but it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.’