Did the US Lockdown Too Late and Open Too Soon?

As the United States experiences a surge in COVID-19 outbreaks with most of it concentrated in regions that avoided the earlier wave that struck the Northeast back in March and April, the media has adopted a new explanation to continue its longstanding rationalization of society-wide lockdowns.

As the argument goes, most European states (including those that were harder hit than the US) followed a “responsible” pattern of quashing the virus through heavy-handed lockdowns and shelter-in-place orders, and only began the reopening process when its data-driven models said it was safe to do so. By contrast, the United States allegedly waited too long to lock down, did so ineffectively, and “rushed to reopen” before the virus was under control.

It’s a convenient narrative for justifying the reimposition of lockdowns, as well as politically chastising anyone who questioned their efficacy in the first place. But is it based on any evidence?

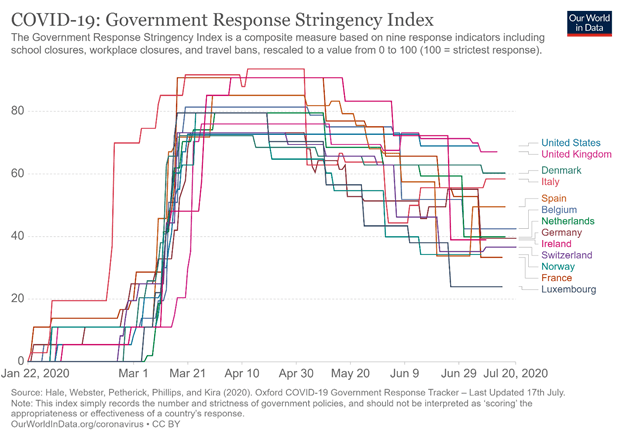

To assist in answering that question, we may turn to a helpful tool created by the University of Oxford’s Blavatnik School of Government that allows cross-country comparisons of the COVID policy responses. Among their trackers is a government “stringency index” that “records the strictness of ‘lockdown style’ policies that primarily restrict people’s behaviour.”

As described on the project’s website, the stringency index assigns scores on a 0 to 100 point scale to capture the severity of a country’s responses. Points are awarded for the familiar suite of nonpharmaceutical policy interventions, adopted in the name of counteracting COVID. These include school and business closures, event cancellations, restrictions on large gatherings, internal and external travel restrictions, and shelter-in-place or lockdown-style attempts to confine residents to their homes.

The stringency index also tracks how these policies change over time, as countries impose greater restrictions or begin to reopen from their previous lockdown state.

So how does the US stack up against other developed countries that locked down? Were we behind the curve in responding to COVID, and did we reopen too early as the current media narrative claims?

Quite simply put, there’s no evidence in the index for either of these assertions. To the contrary, the United States locked down at almost the exact same moment as most of Western Europe.

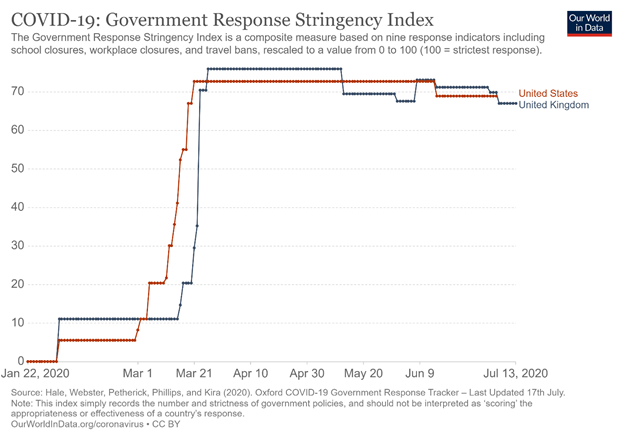

The overall stringency of the U.S. response increased from 8.33/100 on March 1st to 52.31/100 on March 16th, the day that President Trump embraced lockdowns on the advice of the now-discredited Imperial College model of Neil Ferguson. Over the next few days some 43 out of 50 states imposed lockdown policies. The exceptions came from lightly populated rural states that did not experience massive outbreaks, so most of the country’s population was, in effect, under full lockdown. By March 21, the US stringency index rose to 72.69 where it more or less remained for the next two months.

At its peak, the US stringency index reached comparable levels with Great Britain (75.93), Belgium (81.48), the Netherlands (79.63), Germany (73.15), Norway (79.63), Denmark (72.22) and Switzerland (73.15). Among comparable developed nations, only Italy, France, and Ireland topped the 90 point mark on the index.

Of these countries, almost all imposed their most stringent policies at exactly the same time – the week surrounding the March 16th release of the Imperial College report, which also corresponded with the World Health Organization’s pandemic declaration on March 11th. Only Italy – an early hotspot – preceded this wave of lockdowns, having imposed them in late February.

In short, there’s no evidence that the United States lagged behind Europe in its lockdown timing. Nor is there any evidence that the U.S. lockdowns were meaningfully less stringent than the average Western European nation – and this despite having a much larger geography and population.

So what about the alleged “rush to reopen” that the media now depicts as the source of the recent case surges?

Due to its decentralized federalist system, individual US states reopened at different times. Georgia, for example, repealed its stay-at-home order on April 30, and most other US states began relaxing their lockdowns from mid-May to mid-June (although significant restrictions on events, schools, and certain businesses still remain in place in most of the reopened states).

For comparison, most European states began their reopening at approximately the same time in early May and quite a few did so at significantly faster rates than the United States. After Belgium began relaxing its lockdowns around June 8, only the United Kingdom and Ireland remained at a comparable lockdown stringency to the United States, with all three showing scores above 70.

Ireland reopened on June 26 with its stringency index dropping to 38.89. As of July 4th and even with slow reopenings underway in most states, the stringency index shows that the United States (68.89) as a whole still remained under heavier restrictions than any country in Western Europe except for the comparably-shuttered United Kingdom (69.91).

Critics might respond that the difference in state-level policy responses are obscured by Oxford’s national stringency index. And yet current US hotspots did not begin their reopening processes any faster than the typical European states. Texas began relaxing its lockdown on April 30th and Florida on May 4th – approximately the same period that the stringency index began to decline in the Netherlands, Italy, Germany, Denmark, Norway, Luxembourg, and Switzerland.

Perhaps more telling is current hotspot California, the first U.S. state to go under full statewide lockdown on March 19 and one of the slowest states to reopen, having only reached the beginning of its “Stage 2” plan before the recent case surge.

Any number of factors explain the development of the U.S. pandemic at the moment, with little connection to the timing of the lockdowns back in March or the tepid and bureaucratically managed reopening process.

Notably, severe COVID outbreaks appear to be overwhelmingly concentrated in nursing homes – a problem that is not meaningfully addressed by lockdowns, and which did not even figure into the considerations of the Imperial College model on which they were premised. We are also seeing the clear geographic dimensions of the pandemic’s spread. After ravaging the Northeast while it was under full lockdown, viral hotspots have now moved to previously unaffected areas – and irrespective of their remaining or reinstated lockdown policies, as California shows.

The media’s latest narrative however shows the telltale signs of a policy response – lockdowns – in search of a political rationalization. For all the rhetoric and bluster about the U.S. “rush to reopen” and Europe’s allegedly more responsible and effective use of lockdowns, data such as the Oxford stringency index show the exact opposite pattern. The U.S. imposed lockdowns at the same time as Europe, did so with comparable levels of stringency, and actually reopened at a later date and slower pace than most European nations.