Centralized to Decentralized Music in 100 Years

The rise of the bedroom pop stars has delighted consumers and alarmed the music industry, particularly record labels. It’s another sector that is being disrupted by person-to-person exchange.

Some say this is the wrong term: it is really Do It Yourself music. The artist writes the music, lyrics, produces the song, distributes it, and markets it, all with the help of platforms like Spotify that are always seeking new ways to please their customers. Some have experienced spectacular success, and it hints of a musically disintermediated future in which artists themselves reach customers directly. All thanks to technology.

This is the opposite of the way the industry of recorded music began. In the early years of recorded sound, it was obvious that its very existence was beyond belief. If you wanted music in your home before, you had to sing or play it yourself. It could only be “live” music. The phonograph changed everything. Now you could have a machine that played anything.

You have to think back and put your head in the world of 1915 or so to understand the implications.

Mr. Edison

The other day, I and a colleague at the American Institute for Economic Research were out rummaging around antique stores. We came across an old Edison phonograph player in a cabinet, from 1916, Model C-150. It was in beautiful condition and the price was absurdly low. I asked if it worked. The proprietor said of course. She demonstrated it.

The moment was magic. The sound was very clear, the song pretty, and the operation of this amazing machine was just dazzling to behold. It works with a crank on the side. You have to wind it up after every 3 songs, each of which last up to 5 minutes. And I can never quite get over this very obvious but still striking fact: the machine does not plug in and uses no batteries. It is the ultimate in sustainability.

Everyone who has heard this machine since has responded with a broad smile and words of delight.

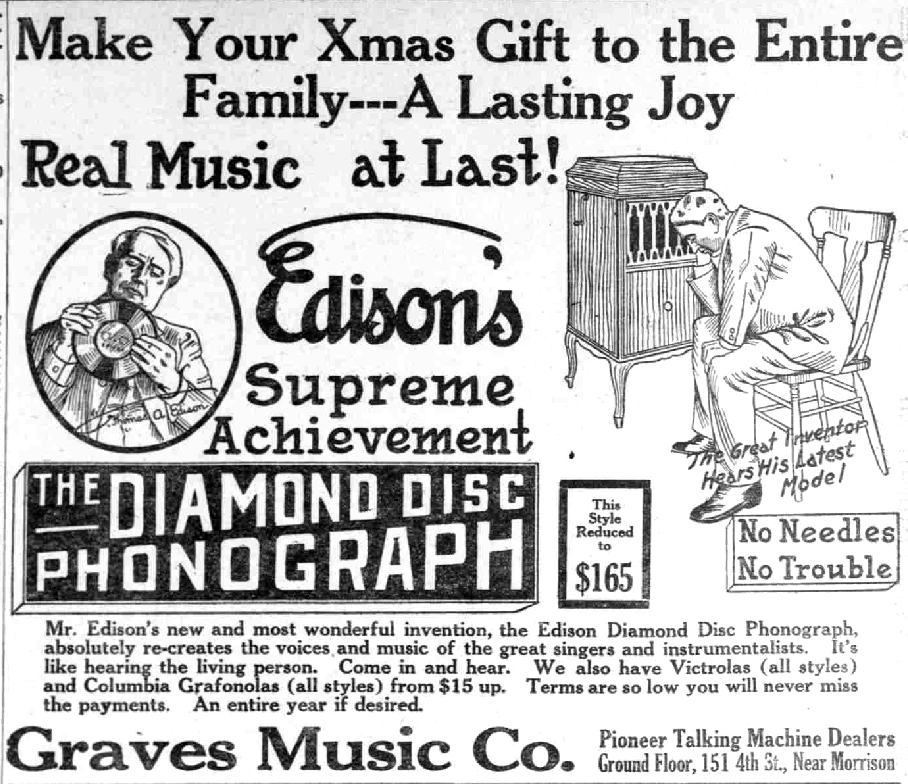

Thomas Edison created this machine to keep up with a big market change from cylinders to disks. Consumers clearly preferred the flat and round style, a preference that persisted all the way to the 21st century. But he was the master user of the patent. He liked to create highly specialized products over which he could enjoy a full government-protected monopoly. So he patented a new form of disk:

Dr. Jonas Aylsworth, chief chemist for Edison, and later after his retirement in 1903, a consultant for the company, took charge of developing a plastic material for the discs. The aim was to produce a superior-sounding disc that would outperform the rivals’ shellac records, which were prone to wear and warping. Another difference from competitors’ discs was that the vertical-cut method was to be used for the grooves. In this manner, the stylus would bob up and down in the groove, rather than from side to side or laterally. Ten-inch records would run for 5 minutes per side at approximately 80 r.p.m.

Keep in mind that it was enough in those days that the thing worked at all and that people could buy this machine for their homes. It cost about $5,000 in today’s terms but it quickly became a household essential (one generation after the household clock was the must-have item). Like the clock, the mechanism was entirely non-electric, running on springs and powered by the human hand and arm.

Remarkable.

But there was a hitch. A real problem. A huge problem actually. Edison held the monopoly on disk production. That means that the Edison company had to provide all the music in addition to the player. That meant that the company had to record music groups to play things. And not just one type of music. There were many tastes out there, even in 1916. There was old-timey folk music, classical music, newly popular jazz, and music of pure nostalgia.

Imagine the challenge of a single company to come up with the full range of music available for the tastes of every composer, from a recording studio in the same plant where the player itself is manufactured. It would be as if the company that made your car radio also produced all the shows on the radio and all the music too.

It’s doubtful that the Edison company had fully thought through the implications of not having licensed production to any other company. Talk about vertical integration not to mention centralization. This strikes us today as utterly unmanageable but this is because we can no longer imagine such a thing. But in the early days of recorded music, it seemed rather obvious that one great company should do it all.

AIER’s Edison phonograph came with 85 disks, each with two sides, for a total of 170 songs. It’s fun to put them on and hear what comes out. Some are completely silly. They must have decided that they needed some classical music, so someone said “The Blue Danube.” A xylophone player was dragged into the studio to play it. That classical music!

Most intriguing is all the Scottish, Irish, and German music in the set of records. What this tells me: there were many second generation immigrants with the means to buy one of these players and then delight their parents with music from the homeland. Some of these Irish songs bring a tear to the eye! The German songs make you want to grab a stein and drink up. The Scottish ones make you feel like you are part of a clan.

Then there are the true American songs from World War I: the marches by John Philip Souza! It’s fun.

And yet, putting on my critic’s hat, I have to admit that the performances are not stellar. Sometimes the music approaches being truly regrettable. But here again, remember that the music itself was an afterthought. The cool thing was that it existed at all.

We’ve come a long way in 100 years. Hey, Google, play Mussorgsky, no Lady Gaga, no Gregorian chant, no Queen, make that a bedroom pop stars mix.