Central Planners Send Vaccines to Places Seniors Don’t Live

Vaccines for flu, pneumonia, hepatitis, and other diseases are normally purchased and distributed efficiently by private physicians, drug stores and clinics. In the case of the Covid-19 vaccine, though, governments relied on central planning and long waiting lines.

Federal officials monopolized the purchase and distribution of vaccines which were sent to state governments, which micromanaged distribution of vaccines to their counties. Vaccines were then rationed by political preferences (such as defining some jobs as more essential than others) and by random luck after spending hours searching for an appointment.

Top-down planning is usually clumsy. Consider how difficult it is to manage even the simple task of geographical distribution. The federal government must figure out how much to send to each state, then states must figure out how much to send to each county. The simplest answer is to base the distribution of vaccines on the total population, but that has been the source of much discontent. Why? Because it provides just as many doses of vaccines for children and healthy young adults as it does for the elderly.

The Becker Hospital Review finds that by February 26, California had received more than 11.9% of all vaccines distributed, which matches the state’s 11.9% share of the national population. Florida received almost 6.6% of all vaccines and has a 6.6% share of the U.S. population. But seniors account for a much larger share of the population in Florida (20.9%) than in California (14.8%). If national vaccine distribution had instead taken account of each state’s share of seniors, then Florida would have received 8.3% of the federal vaccine allotment rather than 6.6%. And California would have received 10.8% of the vaccine rather than 11.9%.

Providing vaccines on the basis of total population would only make sense if anyone believed that scarce early supplies of vaccines should be distributed equally to all residents, young and old alike. But no state is vaccinating children and all of them are prioritizing seniors.

Distributing vaccines on a per capita basis ensures that seniors who live in states and counties with a high percentage of elderly residents will be last to be vaccinated, while those with very few seniors (11.4% in Utah, 12.4% in D.C.) are given ample vaccines to take care of the few seniors they have.

Such interstate misallocation can be greatly compounded to the extent that states make the same mistake by basing each county’s share of vaccine doses on its share of the state’s total population, regardless of age.

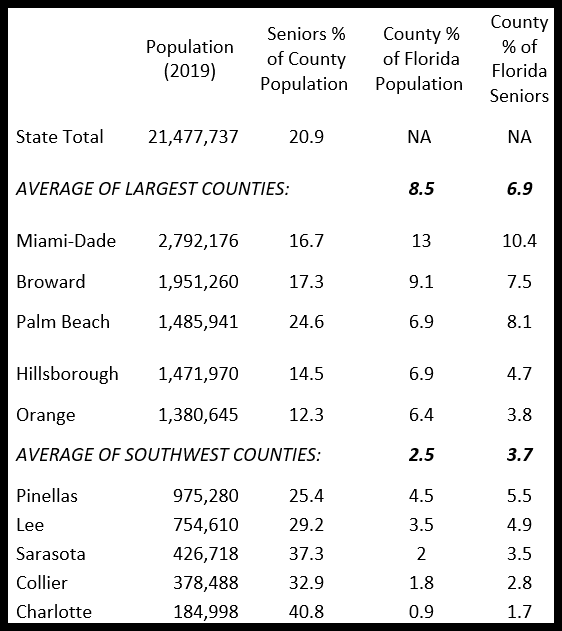

The table compares the senior share of population in the five largest counties in Florida with five others in Southwest Florida (where I live). Florida was one of the first states to start vaccinating all residents age 65 or more and had vaccinated 45% of seniors by February 23. Yet there are widespread complaints in Southwest Florida about vaccines being far more accessible in places where seniors are a relatively small share of the population according to the Census Bureau, such as Orlando (10.2%), Tampa (12.3%), Fort Lauderdale (18%), and Miami (16.9%). Several Collier County neighbors had to travel to those cities for vaccination, so they appear misleadingly in the count of vaccinated residents of Collier County. On the Publix vaccination sign-up website, I have repeatedly found all counties from Sarasota to Monroe fully booked within a minute or two, with 66-91% of appointments “still remaining” after 45 minutes on February 26 in Hillsborough, Orange and Miami-Dade.

As the table shows, Lee County has only half the population of Hillsborough, yet accounts for a larger share of Florida’s seniors. Sarasota is one-third the size of Orange County (Orlando) yet accounts for 5.5% of state seniors compared with only 3.8% for Orange. To the extent that any state’s vaccine distribution plan focuses on each county’s total population, rather than the seniority of its population, too few vaccines will be sent to places where seniors actually live.

County Shares of Florida’s Population and Seniors