Capitalism Saved Sweden

Josh Billings famously diagnosed a problem with beliefs: “I honestly believe it is better to know nothing than to know what ain’t so.” I am astonished at how many students, and for that matter adults, in the U.S. honestly believe that the U.S. should model itself after Sweden because Sweden has shown that socialism works.

I will leave aside the question of whether the U.S. should try to “be like” Sweden; they are very different countries, with different histories and different institutions. But it is important to refute, using simple and widely available empirical evidence, the claim that Sweden is “socialist.” It is not. In fact, Sweden is one of the most robustly capitalist nations on earth.

By socialism, I mean a system that relies on state ownership and control of the means of production, state direction of production decisions, and direct state control of education and employment decisions of individuals. If one does not mean those things, then that would require a little more thinking about what “socialism” means. If by “socialism” you mean prosperity and rule of law, then you are confused.

There are several important issues to discuss, to understand the differences between capitalism and socialism.

First, ownership. Ownership solves the problem of the commons. In capitalism, ownership is (largely) private; under socialism, the state owns and controls the major productive resources of the society. It is sometimes noted that private ownership has a “short time horizon,” as owners focus on profits. But in fact private ownership tends toward valuing the future, because investment now can earn profits in the future.

In fact, it is political incentives that force a short-run perspective. If we are talking about “democratic socialism” (few socialists actually favor Stalinism), then the time horizon of officials does not extend beyond the next election. In the U.S., that means that there is a two-year window, and that is in November of even-numbered years, before every member of the House of Representatives has to stand for reelection. As Marian Tupy wrote:

Historically speaking, environmental damage emanating from socialist production was vastly greater than environmental damage emanating from capitalist production. All and I repeat all academic studies done in the aftermath of the collapse of the Soviet empire found the quality of the environment in the formerly socialist countries to be inferior to those in capitalist countries.

Private ownership provides better information about future values, and better incentives to value the future, than democratic socialism.

Second, opportunity costs. Using prices gives useful signals about relative scarcity, and incentives for decentralized, emergent, but highly organized individual action. A socialist system sets prices, rather than allowing prices to adjust to reflect the dynamics of fast-moving events.

The problem seems like a narrow technical obstacle, but in fact it is fundamental. Top-down social planning is not just difficult; it’s literally impossible. No individual or group can collect enough information quickly enough, and design incentives persuasive enough, to solve the problem, at scale. And by “scale” I mean somewhere around 10,000 total individuals. Clearly, it is possible to organize groups smaller than that using “command” networks, because (as R.H. Coase pointed out in 1937) that’s why there are firms embedded in markets.

For large groups, where individuals operate independently, the knowledge possessed by one person is not communicated to other individuals. That means (as I argued in this video) that the opportunity costs of resources are not represented in the decision process of participants. More simply, you do one thing when you should do something else; I use one resource when I should share or send that resource to someone else who needs it more.

Socialism operates without prices, either because the state is one big firm, with no mechanism for communicating opportunity costs internally, or because the democratic process determines what prices “should” be based on voting, rather than the reconciliation of diverse plans and purposes achieved by market processes.

Third, coercion. Without prices, we must either rely on desires of individual dictators, or state control expressed through majority rule. Without prices in the form of salaries, there is no way to direct people toward job shortages except coercive force. That means that when there is a shortage of one kind of worker, especially in an occupation where there is little social prestige or intrinsic benefit, the state must use the threat of violence to induce people to work.

And where there is a surplus of another kind of worker, especially in an occupation with lots of social prestige and great intrinsic benefits, the state must ration available positions by setting up some kind of wasteful rent-seeking contest. More simply, the only way to get sanitation workers in a socialist system is conscription; the only way to select among the many applicants for teaching positions is to use excessive educational licensing, or favoritism by the authorities.

How do market systems solve this problem? By adjusting the prices we call “wages.” In some cases, that means garbage collectors make more than teachers. Is that “fair”? In a market system, the wages that send signals to people choosing careers are means of directing people voluntarily, rather than coercively. Ideas about how much people “should” make, based on political preferences, are simply disconnected from the economic problem of occupational choice. Socialist systems must, by definition, direct workers into occupations they would not choose voluntarily.

Scandinavia: A World Center of Capitalism

Now that I have discussed the differences between capitalism and socialism, let’s consider the question I started out with: is Sweden socialist? I often participate in debates on capitalism vs. socialism, and students often give Sweden as an example of how socialism “works.” Well, yes, Sweden works, that’s true. But it works because it is one of the most capitalist nations in the world! It became capitalist after trying socialism, and reaching the (correct) conclusion that socialism just doesn’t work.

If you think Sweden is socialist, then you know something that just ain’t so. As has been documented repeatedly by popular treatments and more scholarly discussions, any use of the actual measures of economic freedom that constitute capitalism show Sweden is solidly in the camp of fully market-oriented economies. As Andreas Bergh points out in his 2016 book, Sweden and the Revival of the Capitalist Welfare State, it is inconceivable to think of the Sweden of the current decade as being anything other than a capitalist, and in fact libertarian, country.

It is fair to say that Sweden was socialist, at least in terms of temperament and the direction of public policy. In 1975, Sweden’s state owned well over half of the productive resources in the country, and directed prices in much of the rest. It subsidized debt, in part paradoxically by having enormously high tax rates with generous deductions for borrowers. Its attempts at “Keynesian” policy interventions were clumsy, were mistimed, and created disastrous uncertainty in investment returns even in the portions of the economy that were still market-oriented.

The state taxed successful industries heavily, and used the proceeds to subsidize industries that were inefficient, corrupt, and failing. This meant that interest rates on capital were prohibitive, especially when you tack on double-digit inflation.

To protect workers, the state required that wages could not be cut, and also enforced a panoply of restrictions on firing, layoffs, and other means of adjusting hours. Swedish products shot up in price, and the government was forced into a series of devaluations of the krona that made purchases of imported products beyond the reach of much of the middle class.

The electorate took a dim view of all of this. The tax system was a Rube Goldberg mechanism, with a level of complexity and arbitrary favoritism that encouraged distortion of investment into whatever happened to be taxed less, rather than whatever might produce useful products. Gunnar Myrdal, hardly a conservative, famously asked in 1978 whether Swedes “had turned into a people of swindlers.”

Fortunately for its citizens, but unfortunately for those who think Sweden is still socialist, the Swedish government, more or less by universal consensus, turned sharply back toward capitalism beginning in about 1995. It deregulated domestic industry, privatized its education and pension systems, and opened the economy to international trade and competition. The reason it did this is precisely because capitalism, wherever it is practiced seriously in a system with rule of law and protection for property rights, always creates prosperity.

As Harvard’s Torben Iversen put it, in his book Capitalism, Democracy, and Welfare:

Labor-intensive, low-productivity jobs do not thrive in the context of high social protection and intensive labor-market regulation, and without international trade countries cannot specialize in high value-added services. Lack of international trade and competition, therefore, not the growth of these, is the cause of current employment problems in high protection countries. (p. 74)

At present, Sweden is the 19th most capitalist country in the world, measured based on property rights, trade openness, and freedom to use stock to create new corporations. In fact, Sweden is in the top 15 most capitalist nations in terms of property rights, financial freedom, and business freedom. Most sectors are largely unregulated, and the freedom to move capital makes Sweden among the most capitalist nations in the world.

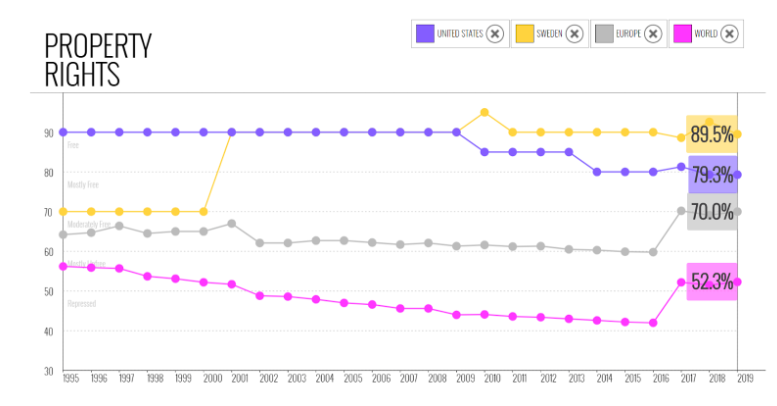

As the figure below shows, this change was sharp, and intentional. Between 1999 and 2001, Sweden deregulated most of its economy, sold off most of its dinosaur-slow state-owned enterprises, and converted substantial parts of its welfare commitments into private systems.

(Generated from the 2019 Heritage Foundation Index of Economic Freedom)

As a result, at present Sweden is the 6th most protective of private property rights, of all the nations in the world. By comparison, the U.S. is 25th most protective, our Fifth Amendment notwithstanding. If a nation has powerful protections for private property, even if the ownership protected is of the means of production, that is not socialism, no matter what you think you know.

- Sweden fully privatized its pension system, moving from “defined benefit” to “defined contribution.” Yes, there is a means-tested add-on guaranteed pension top-up for the least well off, but the first-line system is personal pension accounts, invested in one of 700 private index funds, managed by private fund managers. It is the most privatized pension system, by far, in all of Europe.

- Sweden has a 100 percent universal voucher system for education. There are questions about whether Sweden’s educational system works as well as it should, but it is one of the most private (and not socialist) education systems in the world.

Sweden is not alone in rejecting socialism and embracing capitalism. If you look at the general trend in the countries of Northern Europe, it has become much more capitalist in the past 25 years, after its own failed experiments with socialism. In particular, on the measures I have discussed, Denmark, Finland, and Norway are all three even more capitalist than Sweden.

You may recall that in 2016 a number of Bernie Sanders supporters held up Denmark as the example of the kind of “socialism” they envisioned for the U.S. Speaking at Harvard’s Kennedy School, Denmark’s prime minister (Lars Løkke Rasmussen) told students “[I have] absolutely no wish to interfere in the presidential debate in the US” but politely told them that what they thought they knew about Denmark just ain’t so:

I know that some people in the US associate the Nordic model with some sort of socialism. Therefore I would like to make one thing clear. Denmark is far from a socialist planned economy. Denmark is a market economy…. The Nordic model is an expanded welfare state which provides a high level of security for its citizens, but it is also a successful market economy with much freedom to pursue your dreams and live your life as you wish.

In terms of deregulation of business freedoms, measured in the Fraser Institute’s “Index of Economic Freedom,” Denmark, Finland, and Norway are the 7th, 8th, and 9th most free; Sweden is 12th.

The U.S.? It is 15th. The U.S. is rapidly regulating new industries, and further restricting old ones, at the state level in particular. The expansion of professional “licensing” rules, supposedly for the benefit of consumers but in fact in support of organized corporate interests, is making the U.S. less capitalist every day.

My own view is that the U.S. still has strong institutions of its own, and that we simply need to restore business and investor confidence in our economy. But those of you who prefer the Swedish system, where robust capitalism is used to create prosperity and then redistribution is used to support welfare programs, are entitled to those beliefs.

Just please, please don’t call Sweden “socialist.” ’Cause it ain’t so.