Bohemian Rhapsody Shows That Artists Should Care About Audiences

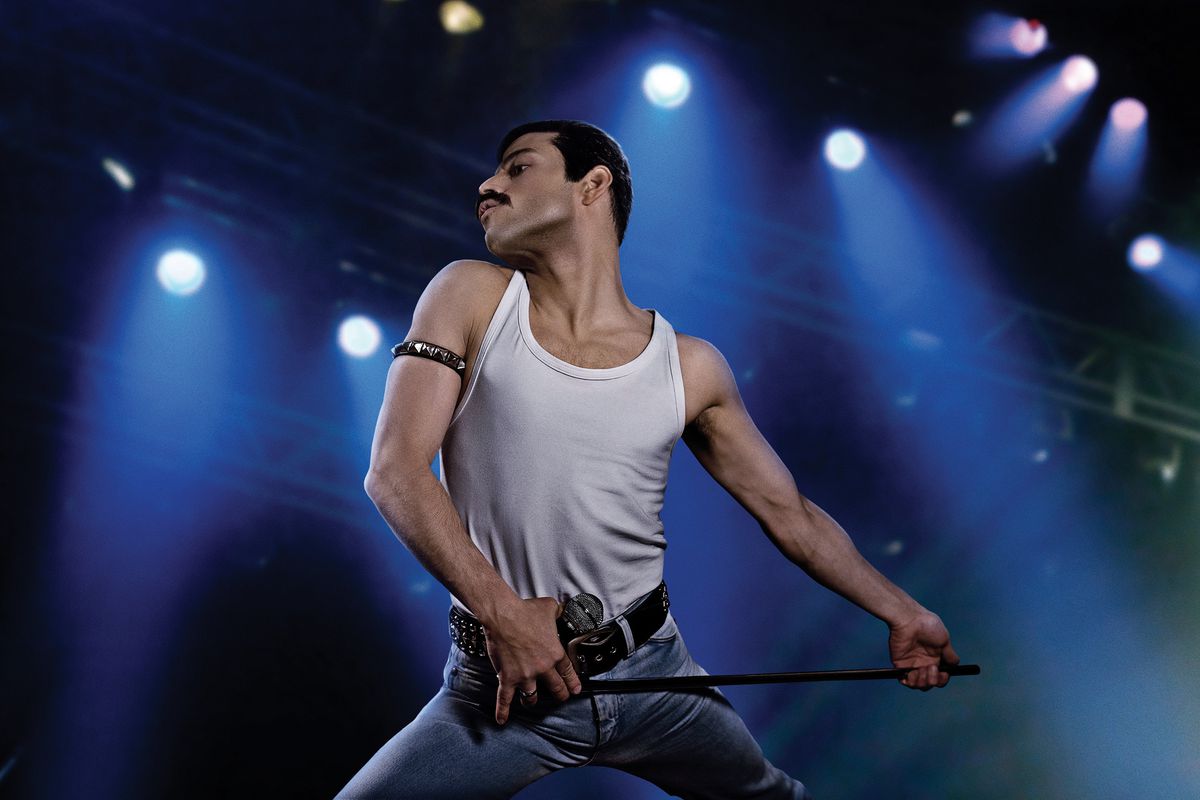

Bohemian Rhapsody, a biographical account of the lead singer of the band Queen, is one of the best films about a great musician that I’ve seen. I say this in defiance of some critics. The rap on the film is that it is too much about the music and the creative and performative genius of Freddie Mercury, and not enough about certain lifestyle issues for which he was notorious.

The opposite is true. The failing of most musician-centered movies is that there is not enough about the art itself. I’m thinking of Immortal Beloved (1994). If you wanted to see a movie about Ludwig van Beethoven as a musician, this was not it. You would think that his real passion was not his art but some secret unconsummated love. Even Amadeus, while better than most attempts, was disappointing in this respect.

It can be difficult to find actors who can provide a compelling recreation of musical greatness. But to bury the story of art in the muck of personal eccentricity is not a good way to honor genius. Bohemian Rhapsody is foremost a film about an amazing singer and a creative process that rocked the pop world through the 1970s and 1980s and left us with iconic songs that changed everything. The movie presents the creative process here realistically and with exciting drama.

Commerce and Art

Even better, this film has a lesson that pertains to the creation of great art in a commercial society. Queen was rewarded in every way for making music that people love. Yes, the same could be said of many top pop artists today. Maybe this doesn’t sound like a radical proposition, but there is a tendency in high-end musical circles to believe that quality and popularity are mechanistically opposed to each other.

If you get famous and rich, you must have “sold out.” If you borrow pop tropes for serious music, you have compromised your art. The tendency to believe that there must be a high wall between artistic integrity and commercial success stretches far back in history, and is with us still.

At the age of 16, I was sure I would become a lifetime professional musician, so I started hanging out at the school of music during as much spare time as I had. I began to notice a certain ethos alive in these circles. They didn’t like audiences. They didn’t like customers. They saw every demand that their art be deployed to please popular tastes to be a terrible imposition. They wanted to be exempt from economic forces at work. I could hardly stand it, so I changed my life plans and, in reaction, went into a field that celebrated commercial life (economics).

Sacred and Secular

The perception that commerce and art don’t mix created a notorious case in the 16th century. Orlando di Lasso was a much-beloved composer of polyphonic Catholic Church music. Many of his masses and motets became standard performance repertoire in cathedrals all over Europe. The clerical class delighted in their pious sound and quality of inspiring prayer and soulful reflection.

Then one day, someone noted a certain familiarity to some of the melodic structures. Sure enough, they were identical to some folk music popular among the less-than-spiritual crowd. Some were drinking songs. Some had bawdy lyrics. His “Missa Entre vous Filles” was based on tunes that included lyrics that can’t be printed here. Panic ensued and di Lasso’s compositions were quickly banned.

This was not uncommon in the age of faith. There was a perception that music composed for a high-end purpose could never be tainted by musical forms coming from secular life. Two centuries later, with the rise of commercial culture, opportunities for composers to rely on ticket sales and sheet music sales increased. No longer was patronage the only option.

But even here, the perception that commerce would taint serious music persisted. And it persisted despite all evidence. G.F. Handel moved from Germany to Italy to England chasing commercial opportunities. He reused tropes from his Italian liturgical music for his English oratorios. And the themes of his oratorios finally settled on stories from Hebrew scriptures precisely because these stories experienced popular success in 18th-century England.

Some people might imagine that someone like J.S. Bach would be free from such grubby commercial dealings, but his hundreds of cantatas were written as a job obligation in exchange for wages. His famous Brandenburg Concertos were composed as demonstration projects when seeking a new gig. And just as with later composers like Johannes Brahms, he paid the bills through teaching far less than through performance. Other composers like Gioacchino Rossini and Giuseppe Verdi experienced wild popular success, while Richard Wagner became the subject of a cult of his own.

Keep in mind that all of this happened before the advent of musical copyright. Bach, Mozart, Brahms, and Beethoven all managed some degree of commercial success without using the law to maintain exclusive rights. They relied on teaching, concertizing, and marketing first-run access to their newest compositions. Once universal copyright came into being with the Berne Convention, there was a new complication: composers believed they could never borrow from contemporaries, whether low- or high-brow sources. But the result was new forms of “serious” music that stopped connecting with audiences completely (who listens to 12-tone rows to relax at home?).

Now to Queen

Queen distinguished itself for its focus on connecting to listeners in a special way, but the band achieved this not through mimicry but innovation. The movie recreates the moment when the band reluctantly decides to try its hand at disco forms. No one was truly happy about the idea until the bass player pushed out the affecting (and apparently eternal) riff from the opening of “Another One Bites the Dust.” Probably a majority of the human race today can recognize the song just from the beat and the three-note pattern it covers. It’s even used in CPR training so that people know how quickly to compress the chest.

As for the signature song of the band, the wildly weird and enormously popular “Bohemian Rhapsody,” the piece redefined what could be popularly played on the radio. It evokes a strange seriousness with its operatic motifs, dire subject matter, and implausibly smooth transitions from one style to another. The band’s producer completely ruled out its release as a single, based on conventions of the time. He was wrong. The song is considered one of the greatest in the history of pop, even achieving a number one status twice.

The movie tells the story behind the song and the band’s ambitions to cross over into several genres. It remains a paradigmatic refutation of the idea that there are tall walls that separate serious art from commercial success. My impression is that these walls today are not nearly as high as they were several decades ago. (The Atlanta Symphony hosts pop artists, folk artists, known musicians from all genres, all in the same season as it presents Mahler’s 7th to adoring audiences.)

The wonderful movie based on the life of Freddie Mercury and his band makes a great case that commerce can be and is the friend to art. It has always been so, but we are only now fully coming to terms with what this implies for the artistic endeavor generally.