Blockchain Works Like Money in Yap

I’ve sensed for some time that people tend to exaggerate the newness of cryptocurrency, as if it were a technology never before imagined or experienced, meeting needs that were heretofore never felt.

This is not true.

For so long as humanity has existed, there has been a need to have some method of knowing of and/or documenting ownership claims. You can hold your property (that you claim is yours) and defend it against invaders. Or you can go one better and develop a social consensus technology to record who owns what. This improves life for you and everyone.

This documentation can take place on stones, clay, papyrus, parchment, vellum, or databases. The problem with all of these methods is the same: centralization. If there is only one record and one record keeper, there is always uncertainty over fraud, manipulation, or decay in the record itself.

This is where blockchain technology provides a remarkable innovation. Ownership claims live on a ledger in the cloud. Rights are moved by proof of work and proof of authority. When the ledger is changed, everyone can observe the results. Algorithms rather than human discretion drive the system, thus eliminating the possibility of ambiguity and fraud.

This is a technical innovation. But it is not an innovation in how we aspire to live. There is a big difference. The blockchain allows people to achieve something we have always wanted to do but haven’t been able to do until now.

If that is true, can we find other historical examples of blockchain-like technology? A new paper published by the Federal Reserve claims to have found one. It comes from the island of Yap, a tiny place among the Caroline Islands of Micronesia.

As I was reading about this place and its people, I kept thinking (forgive me) of the movie Moana and the struggles of these island people. The Disney movie didn’t feature any money in the community; for all we knew the people live in a happy communism of some sort. I knew there had to be something wrong. Everyone needs property rights. Everyone needs money. Everyone needs a way to keep track of who owns what.

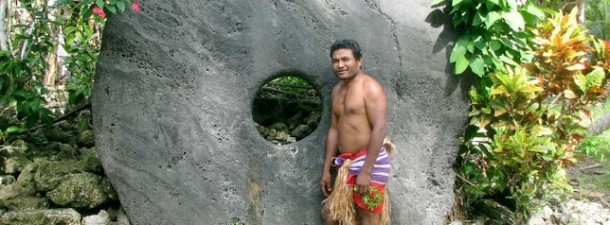

It turns out that the island of Yap provides an amazing example of blockchain technology…of sorts. The authors of the Fed paper state that the monetary system of Yap relies on a form of this very thing. And this has been true for thousands of years, and remains true today. It is known the world over as the Island of Stone Money.

The great Milton Friedman took an intense interest in the monetary system of Yap and even wrote a full paper on the topic.

The monetary base is called the Rai. It is a huge rock made of limestone. These rocks come from 400 miles away and are extremely difficult to transport. Over the centuries the people of the island learned to make them in the shape of donuts to make them easier to move. If you want “proof of work,” here it is!

But if these rare objects serve as money, how is trade conducted? This is where it gets extremely interesting. They do not move physical stones. All stones stay where they are. They are revered and protected. What changes hands is an understanding of who owns what. You bargain with others and communicate the results.

All reports say that there are about 5,000 people on the island with a stable population. The people involved in trading with money are a small minority. The key here is everyone with a stake in the system shares information about changes and truly remembers how rights in the stones are allocated. Apparently, at some point in history, marks were made on the stones but once the system grew to a certain level of sophistication, this was no longer necessary.

This knowledge persists and lives throughout the community. You can call it a blockchain of the mind. If all of this sounds crazy, remember that such “primitive” communities can exhibit a ridiculously high level of intelligence in ways that people of the “developed” world cannot even imagine. That everyone can share knowledge of ownership rights in a particular kind of money, with full clearing and no counterparty risk, requires a high level of trust. The people of this island evidently have exactly that.

I appreciate this example because it illustrates that while blockchain is new technology, it solves a universal human problem. In this sense, it is like every great innovation in history. We’ve always wanted to communicate, travel, light our rooms with a switch, fly through the air, stay warm in winter, and so on. Railroads, electricity, flight, and indoor temperature control did not create new needs; they solved old ones.

It is the same with blockchain. That we have a glimpse of a more secure way of changing and tracking ownership rights, make deals possible, facilitating trade and other forms of human engagement, is mighty impressive. This technology exists. Nothing government can do to regulate it is going to cause it to un-exist. Our lives will be disintermediated and different. We will love the results.

Maybe someday we too can be as “primitive” as life on the island of Yap.