Biodiversity and Prosperity Go Together

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is clear: there is a loss of biodiversity globally. The losses are expected to increase as a result of climate change. As a result, there are some researchers who advance the idea that we may be in the Sixth Great Extinction.

However, it must be pointed out that numerous studies identify that there are some areas that are experiencing gains in biodiversity (including in marine coastal ecosystems). The gains in those areas are too small and are occurring at a pace that is too slow to offset losses elsewhere. Moreover, some areas are also experiencing stability in biodiversity.

However, these gains are very instructive. They tell us that, if we care about biodiversity, wealth institutions are the key elements to understand.

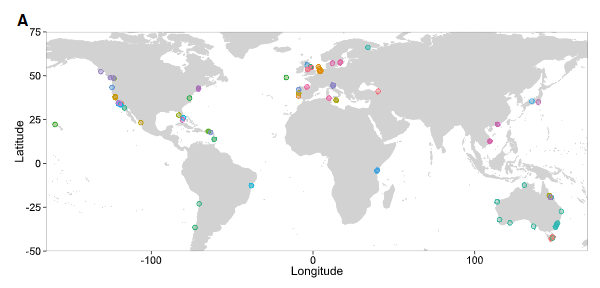

The map below shows a sample of areas that was used to document an increase in local biodiversity in recent years. Most of these areas are wealthy ones. This would be consistent with the idea of the Kuznets curve that suggests that environmental quality ought to improve with income (after a certain point). The Kuznets curve argues that as we grow richer, we start using less land (and other resources) and thus encroach less on the environment. Simultaneously, when we are rich, we can better afford the costs of environmental regulation. Thus, it should be unsurprising that the areas in the map below show, on average, gains in biodiversity as they tend to be mostly in richer countries.

However, the applicability of the Kuznets curve to biodiversity is debated. Some argue that, yes, growth eventually leads to gains in biodiversity. Others point to an answer in the negative. There are good reasons to side with the “yes” side since the articles that fail to find a Kuznets curve probably suffer from a well-known econometric problem: multicollinearity. Normally, when we try to estimate the effect of a given factor on a variable of interest (e.g. biodiversity), you want the explaining variables to be independent of each other.

Thus, if you want to assess the effect of income on biodiversity, you have to make sure that the other variables affecting biodiversity are not determined by income as well. One such example here is farmland. As countries grow richer, they tend to have smaller agricultural sectors. This is why most developed countries have seen the total land area used for agricultural ends fall since the 1950s. Thus, using both agricultural land area and income per capita will affect the quality of the estimates produced by econometric analysis. The few papers that avoid such a problem, such as this paper in Ecological Economics, find evidence of a Kuznets curve.

Nevertheless, it is important to allude to a crucial point here: institutions matter. The papers that find the absence of a Kuznets curve tend to omit the role of institutions. Yet, it is entirely possible for institutions to be, on average, positively linked with overall living standards but nevertheless be tilted in favoring of eliminating the Kuznets curve with regards to some environmental indicators.

Thus, wealth may have uneven effects on environmental quality and biodiversity. However, institutional quality will have a clear and more stable effect. Indeed, the articles that include measures of institutional quality such as “economic freedom” (as measured by the Fraser Institute) find the presence of a positive effect on biodiversity. More micro-level studies such as those concerned with fisheries management suggest that where property rights over high sea fish stocks are established, marine populations are recovering.

This is a crucial point: the positive impact of wealth is conditional on institutional quality. If one cares about species loss and biodiversity globally, one can learn from the few places that are experiencing gains in biodiversity. Indeed, the areas on the map above are not only wealthy, but they also tend to be ones with well-enshrined property rights regimes and high levels of economic freedom (which I take as a measure of institutional quality). This is indicative of how efforts to preserve biodiversity ought to aim at both improving institutional quality and economic growth.