Backdoor Censorship through Libel Law

There is a growing consensus that, as Russ Douthat puts it, “Trumpism as an ideological revolution, whether akin to Roosevelt’s or Mussolini’s, has mostly evaporated.” Maybe. Let’s talk about one aspect of Trumpism that has received very little attention: his persistent call for tighter libel laws as a way of controlling the press.

Trump reiterated his demand last week in the public portion of a cabinet meeting. “We are going to take a strong look at our country’s libel laws,” he said, “so that when somebody says something that is false and defamatory about someone, that person will have meaningful recourse in our courts.”

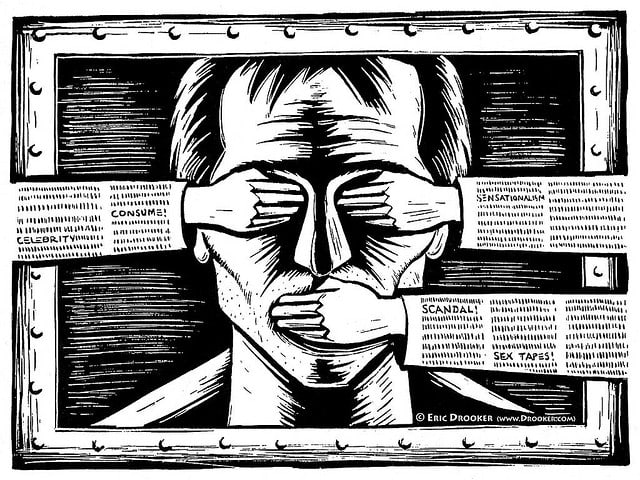

It’s not called censorship, but that’s what it is: government using coercion to make the press fearful of criticizing the regime. This is nothing new. This is how libel law has always worked.

The First Amendment

Today, the United States is one of the best spots in the world for freedom of the press. The courts do not stand ready to persecute people for saying and printing things merely because they annoy people with power. In this way, the US is far ahead of most countries in the world, where libel law is frequently used to quash the freedom to speak.

This is an especially pressing issue in times when anyone with a Twitter account has the power to reach billions. We are all members of the press. We all need the freedoms that only decades ago were mostly used by major media companies.

It wasn’t easy to achieve this.

After the founding, we eventually got the First Amendment but this wasn’t in the first draft of the Constitution. The Bill of Rights came about through a compromise just to get the thing approved by the states. But even then, press freedom wasn’t taken that seriously by the ruling class. Little more than a decade after ratification, the Adams administration shoved through the Alien and Sedition Acts.

These laws, which essentially criminalized libel of a public official, were widely seen as despotic. Many people were accused of crimes for saying something bad about the head of state, just like in the old world that America was founded to leave behind.

The public anger at these laws was so intense that the radical liberal Thomas Jefferson won the 1800 election by campaigning against them. The First Amendment was saved. But the struggle for a consistent defense of the freedom of the press didn’t end there. Censorship laws kept coming back, especially in wartime in the 20th century. Woodrow Wilson and FDR both imposed horrible restrictions on speech.

The Prevailing Rule

These days, we are mostly safe from such impositions using the excuse of libel. It is almost impossible for any public figure successfully to sue for defamation under any existing libel law. Court precedents have established that the plaintiff has to prove that the writer had “actual malice,” fully intending to inflict real harm by deliberately making up false information. That’s a very high bar, as legal experts say.

This is not true in Latin America or Europe, where the press faces down government agents regularly, who manipulate libel law in order to crush criticism they don’t like.

The 1964 Supreme Court case The New York Times vs. Sullivan established the existing rule. By way of background to this case, during the civil rights struggles of the 1950s and early 1960s, many reporters were nervous about reporting on lynchings, police abuse, and various other indignities suffered by black Americans because cities and counties could successfully sue for defamation. The courts would frequently side against the press, which was forced to pay up. Libel litigation was how the segregationist press beat back investigative reporting.

The result was not overt censorship. The practice created what was called a “chilling effect.” Writers would refrain from publishing certain claims for fear that someone would get upset, sue, and cause government courts to pillage the property of the media outlet. Rather than take that risk, the press would self-censor: no overt laws were necessary; one only needed the threat of a libel suit to control the information to which people had access.

In the New York Times case from 1964, the paper had printed an ad that claimed Martin Luther King, Jr. had been arrested seven times when he had only been arrested four times. The Times printed a retraction, but the head of police in Montgomery, Alabama, was not satisfied. He claimed personal injury to his reputation. The case went to the Supreme Court, which decided that the Times had made a mistake and not spoken out of actual malice, thus rejecting the plaintiff’s demand for damages.

Since then, and mostly because the bar for libel cases is so high, the freedom of the press has been mostly guaranteed in law.

The Chilling Effect

The entire idea of a “chilling effect” came about in the context of libel. If you have to face the prospect of a permission-giving institution with coercive power, you will refrain from saying what needs to be said. As John Milton wrote in 1644:

For to distrust the judgement and the honesty of one who hath but a common repute in learning and never yet offended, as not to count him fit to print his mind without a tutor or examiner, lest he should drop a schism or something of corruption, is the greatest displeasure and indignity to a free and knowing spirit that can be put upon him.

There we have it: it is a matter of human dignity that a person should not be coerced in the printing of an opinion. The US today provides such protections for print, but less so for other media. Even today, many television and radio broadcasts are subjected to forms of censorship.

The printed and digital press has been more-or-less secure, and unusually so.

Eye of the Beholder

An example of how the rule is breached is provided by Victorian England, which had strict laws regarding obscenity. How that was defined was left to the groups who complained loudest. The courts tended to back them. In many cases, the law was invoked against individuals who attempted to publish material about birth control for women. This shocked sensibilities enough that the press was shut down using the excuse that such talk was obscene.

Oddly, in those days, there were no actual laws against advocating for birth control anywhere on the statute books. But the chilling effect was in place due to courts that were friendly to litigants who wanted to stretch the definition of obscenity as far as it would go.

The analogy with libel is clear. Without a clear standard set by the courts, the press is made vulnerable to every manner of lawsuit from any party that imagines itself damaged.

It took half a millennium to arrive at institutions that established a clear wall here: the state may not, regardless of the excuse, interfere with people’s right to express a thought. Nor may the courts act on behalf of any private party that claims to have been injured, unless that private party can prove actually malicious intent and real damage.

Today in the US, there is a high wall between the state and the freedom to speak in print (which includes digital publication).

But how thick is this wall? There are always pressures to penetrate it. It is a problem, too, that the law is not well understood by the public, which takes the freedom so much for granted that there is little consciousness of the dangers of a politician who rails against the media for propagating “fake news” (which, like obscenity, obviously exists in the eye of the beholder).

The Trump Challenge

During the campaign and after, Donald Trump has repeatedly threatened to “change libel law” to open up the press to lawsuits.

“I’m going to open up our libel laws so when they write purposely negative and horrible and false articles, we can sue them and win lots of money,” Mr. Trump said during the campaign. “We’re going to open up those libel laws. So when The New York Times writes a hit piece which is a total disgrace or when The Washington Post, which is there for other reasons, writes a hit piece, we can sue them and win money instead of having no chance of winning because they’re totally protected.”

Obviously such talk directly contradicts prevailing law, which serves as a bulwark of this essential freedom at least. He has gone so far as to found Trump TV, which offers Soviet-like reports such as this one. It is certainly free of anything remotely resembling libel against Trump:

Should Trump prevail in his wishes, a freedom that all of us take for granted – the freedom to criticize government officials on our blogs and social media – would be severely curbed. It would be the 1790s all over again.

Despite the tough talk, there is actually nothing Trump can do to change the Supreme Court’s precedent on the matter. He cannot issue an executive order, thank goodness, and he cannot rely on Congress to act with some new censorship law on the order of the Alien and Sedition Acts. We’ve been there and done that. Obviously, reverting back to old forms would be a disaster for hard-won freedom of the press.

The Freedom Ideal

Now, we might ask the question: how does a truly free society deal with the issue of libel? Should it be the case that the press can just say whatever it wants about a person?

The standard was elucidated by Walter Block. In his view, no one has an enforceable right to a reputation. Words are not themselves aggression and hurt feelings entitle no one to the property of another. In effect, Block would go much further than the Supreme Court and make it absolutely impossible for anyone to sue anyone for libel ever. As he writes in Defending the Undefendable (1976):

“Now, there is perhaps nothing more repugnant or vicious than libel. We must, therefore, take particular care to defend the free speech rights of libelers, for if they can be protected, the rights of all others—who do not give as much offense—will certainly be more secure. But if the rights of free speech of libelers and slanderers are not protected, the rights of others will be less secure.”

But what would be the results in a world in which anyone can say anything he or she wants? Expectations would adjust, same as they have adjusted for “fake news” today. As Block says: “The public would soon learn to digest and evaluate the statements of libelers and slanderers—if the latter were allowed free rein. No longer would a libeler or slanderer have the automatic power to ruin a person’s reputation.”

In other words, people have to learn that it is not the job of government to stamp a guarantee of truth on the press. Nor it is a government function to weed out information from the media that powerful people do not like.

You don’t have to go as far as Block in effectively abolishing the entire concept of libel to see his point. The freedom to speak and write need firm protections in the law, approximating what they are today under since 1964. Civil libertarians should be highly sensitive to any head of state who makes noises along the lines that Trump suggests. It is very recognizable, salient, and very alarming.

We’ve fought too long and too hard against government encroachments to accept the slightest compromises to the firm principle of the freedom of speech. Trump’s threat is not about protecting truth against lies; it’s about government control over speech so that people who criticize the regime can be forced into silence.