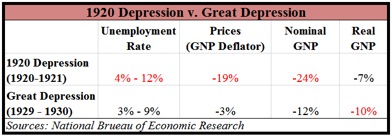

1920 Depression v. Great Depression

There is a reason why you’ve never heard of the depression that began in 1920. While the stats vary, the first year of the 1920 Depression was worse than the start of the Great Depression in many ways, and was arguably the most deflationary year on record. However, during the 1920 recession, the government did not act with the conventional low interest rates and deficit spending that started with the Great Depression. And while the results might surprise many today, it is not a coincidence that the 1920 Depression was so short lived that history usually overlooks it, but the memories of the Great Depression still lingers.

The above table indicates the severity of the start of the 1920 Depression with regards to the change in unemployment, prices, and production. Now according to the vast majority of today’s economists, business leaders, and politicians, the government would have needed to intervene on a grand scale in the form of massive deficit spending and low interest rates in order to prevent the economy from falling into a never ending tailspin of depression. That is exactly what the Secretary of Commerce, Herbert Hoover, suggested when he stepped in office in 1921. And despite popular misconceptions, that is exactly what Hoover (as president) and the Federal Reserve did during the onset of the Great Depression.

However, President Wilson reacted with the conventional approach (at the time) by not intervening, and slashed government spending by 20% from 1920 to 1921, despite a 16% reduction in tax revenue. Because spending cuts were so deep, the government racked up a relatively large $509 million surplus in order to start paying down the debt accumulated during WWI. When President Harding took over in March of 1921, he ignored Hoover and continued in his predecessors footsteps by cutting government spending another 35% and increasing the surplus to $736 million the following fiscal year. Instead of fighting deflation, the Federal Reserve refused to budge after increasing its key interest rate to its highest level at the time from 4.75% in January 1920 to 7% in June. So what was the supposedly catastrophic outcome?

By the summer of 1921, production began to expand and unemployment started to fall; the depression ended in just over a year. It was only then that the Fed marginally lowered interest rates. By 1922, the unemployment rate fell to 8% and then to 3% by 1923. With the help of a huge deficit free tax cut across the board (made possible by spending cuts), the Roaring Twenties were off and running. Given the stark distinction in fiscal and monetary policies, mainstream economists simply have no explanation for the 1920 Depression. But understanding the 1920 Depression explains the longevity of the Great Depression and why today’s economy has continued to suffer.

The shortness of the 1920 Depression was due to the government’s decision to allow interest rates to rise, prices to fall, and unhealthy banks and businesses to fail. As a result, healthy firms took advantage of the collapse in production costs and lowered prices to naturally stimulate consumer demand. Higher interest rates encouraged more savings and healthy firms used the new capital to expand and hire the unemployed. When the government cut billions in unnecessary spending, it freed up scarce resources that healthy firms used to further expand production and employment opportunities. Because President Hoover and the Fed bailed-out the failing and unproductive firms, the healthy and productive companies could not grow. Consequently, production (Real GNP) contracted more during the start of the Great Depression relative to the 1920 Depression.

The truth is that recessions are not diseases, but cures for economic imbalances caused by artificial low interest rates during preceding booms. The 1920 Depression is essentially no different than any other recession. Any time banks issue loans not fully backed by cash held in saving accounts, they inflate the money supply and sow the seeds for a future economic contraction. The depths of 1920 Depression resulted from the massive inflation the Federal Reserve created to help the government finance WWI.

It is true that if the government responded to the housing collapse in the same manner as the 1920 Depression, 2008 would have been worse. Yet high unemployment, stagnant growth, and falling real wages would not be a problem 7 years after the start of the Great Recession that nobody will forget.

Devin Roundtree received his M.A. in economics from the University of Detroit Mercy.