Who’s to Blame for the Rash of Short Squeezes?

The short squeeze in GME (GameStop) over the past few days has captured widespread public and media attention. The stock, which has traded for years in the single digits and teens, ran up to over $350 per share – a gain of $200 per share today alone, suggesting that the entities who held large short positions (bets that the stock would decline) have thrown in the towel. No one knows what the damage is, but no doubt a handful of hedge funds are hurting, having had to buy their positions back far higher than when they sold them. More details will come out over the next few weeks.

The average share price going back roughly one year is under $11. As of today’s closing price GameStop’s one-year return is 7,216%, with the last five trading days seeing a return of nearly 900%. (Having said that, the stock has remained active – hours after equity markets closed.)

Two other facts are now known. One is that a primary force in the upward pressure that caused short sellers to cover (buy back their position) is a somewhat new factor in financial markets: groups of retail (individual) brokerage traders conversing, suggesting, and then acting, roughly in concert, to impact certain stocks.

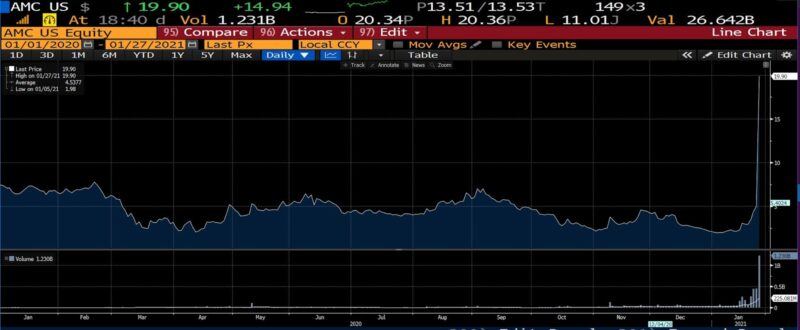

The second is that, having now exacted what one assumes is a tremendous profit in GameStop, they seem to have turned their attention to other stocks, including AMC Entertainment Holdings (AMC):

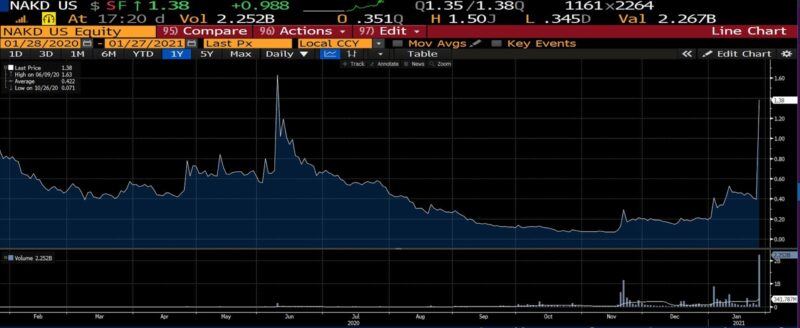

And Naked Brand Group (NAKD), as ZeroHedge pointed out:

The fact is that the short interest in GameStop which attracted the “squeezers” wasn’t of their making. Ultimate culpability lies at the feet of the monetary authorities who, as has become their perennial response to financial challenges of any type or severity, chose to infuse the economy with trillions of dollars in liquidity.

The effect of expansionary monetary policy is well documented and examples of equity, fixed income, derivatives, or other asset classes grossly exceeding historical values without any change in their fundamentals needs little verification. So too, the effects of a rapid increase in the money supply on speculation. Although packs of hunting retail speculators have already turned their sights on a handful of other equities – they seem, from my own eyeballing of it (and it’s not “rocket science”) to be focusing on issues with very high short interests – there are other factors at play here. First, as was seen with Hertz early last summer: when tens of millions of people are unemployed and underemployed, with no sports to occupy them, trading via such low cost apps as Webull and Robinhood is an unsurprising outlet. Second, video games have no doubt grown in popularity during the lockdowns and amid stay-at-home orders, so GameStop’s stock may have risen a lot.

The fact remains that between the stock market crash on March 16, 2020 and this past Monday (January 25, 2021), the Dow Jones Industrial Average rose 53%, the S&P 500 rose almost 62%, and the Nasdaq Composite rose a whopping 97%. Plus, we’ve seen astronomical moves in such stocks as Tesla, up 889% over the same period. Groups of retail traders hunting from among the most overvalued stocks is far from surprising; indeed, it’s somewhat curious that it took them this long to discover what is, among a different and much larger class of speculator, a pretty straightforward means of extracting profit from hedge funds: engineering short squeezes.

Early this evening the Securities and Exchange Commission issued a “Joint Statement Regarding Ongoing Market Volatility” in which it noted that it was watching market conditions closely: one surmises that has more to do with roving packs of small speculators preying upon large speculators than the Dow’s 633-point (just over 2%) fall today. It would be unprecedented for the SEC or another regulator to shut down any of the large Reddit groups who, purposely or by means of spontaneous order, are pushing stocks with hugely asymmetric long-short balances around, but that doesn’t mean it won’t happen.

What will almost certainly not happen, though, is fault be laid where it belongs. First, governments levied destructive policies on their economies, wrecking hundreds of thousands of businesses and sending hundreds of millions, worldwide, into unemployment, poverty, hunger, substance abuse, and suicide before much was known about the spread of a novel virus. Central bankers and state treasuries then pulled out all the stops to attempt to slow the onset of a huge, artificial depression. And as facts regarding the disease became clear, politicians were, owing to both the upcoming US Presidential election and their own reelection chances, unwilling to change direction.

Cantillon Effects – the description of the phenomenon whereby those who get newly created money first influence relative prices – came into effect; financial markets are often first among those. (While true anywhere that demand curves slope downward, some extreme examples are readily available.) One can imagine that, among others, some of the trillions of dollars that the Federal Reserve pumped into the financial system to buy Treasuries (as that market came under historically severe strains) put liquidity into the hands of firms who, understandably, directed it into the equity markets. Stock markets ran up to levels never before seen, exceeding even the heights they’d obtained before anyone had even heard of SARS-CoV-2.

That set the stage for institutional short sellers, which set the stage for retail-induced short squeezes. There will likely be recriminations of all sorts: closures of certain chat rooms or internet discussion boards, restrictions on short selling in certain stocks, and lawsuits between investors and hedge fund managers. (Even now, rumors about a number of short-selling funds experiencing liquidity problems and certain chat rooms being shut down are swirling.) But ultimately the fault is not with retail brokerages or Main Street, nor in hedge funds building outsized (and considering the illiquidity of some of them, unwise) short sale positions in certain stocks, but in the Eccles Building on Constitution Avenue in Washington, DC.