The Scandinavian Experiment: Open vs Close

Everyone agrees that people’s life and wellness are more important than GDP figures. But GDP figures are not only the invention of cold-hearted economists with nothing but monetary transactions on their mind. They capture something in the real lived experience of human beings: incomes and earnings, consumption of goods and services that we use to sustain and enrich our lives, entrepreneurial investments to improve them even more.

GDP captures value. Not exactly and not precisely, and we can endlessly quarrel over its use and misuse; it remains undeniable that they reflect some underlying grassroots economic development rather than the all-encompassing attention to decimals that news coverage may imply.

In the corona crisis, there’s a similar anger towards people pointing out that maybe – just maybe – economic life also matters; that perhaps virus victory at all costs is not worth it. The corona disaster seems to be measured solely by the number of dead. If you think that’s all that matters, you need to raise your gaze from your locked-down window, beyond some cherry-picked story from your local hospital or your frantic epidemiologist – and reassess your priorities.

One does not have to be a cold-hearted economist to grasp that at some level of societal and economic collapse, the number of lives saved and people avoiding infection is no longer worth it. The quality of life for those forcibly isolated matters too. And yes, economic damage is of crucial importance.

As the media and civil society’s sole topic of conversation has become deaths, case fatality rates, supply shortages in hospitals, and high-flying politicians riding to our rescue with money bags, it is understandable that the verdict of countries’ actions is assessed with present infection numbers or per capita deaths in mind.

This is a mistake.

At least three more things greatly matter: the collapse in GDP, GDP per capita and the accompanying explosion of job losses, unemployment and loss of income; the loss of assets, be that through stock market investments of the value of small businesses previously in operation as well as the ever-bloating government indebtedness; and the unmeasurable lived individual experience.

Being relegated to one’s home for a few months and having all Spring events and gatherings cancelled may be a welcome respite for those who jam their calendars with too many things, but a misery for the rest of the population, especially for those whose livelihood depends on it.

Only in hindsight, say in 6-12 months, will the full tally of infections, critically treated, and total deaths clear up. Only when income numbers and GDP declines can be reasonably assessed, when the full extent of governments’ relative debt burdens can be accounted for, can we really say how bad the coronavirus of 2020 was. Only when taking those results into account and deflating them by the lived experience of people consigned to their homes can we assess whether it was all worth it.

The Corona Battle over Scandinavia

But without the experiment of countries and states operating differently, we couldn’t hope to identify what has and hasn’t worked.

The main political and intellectual fault line now goes between those who, in the name of health, wish governments to suppress their unruly citizens and those who fear for the social, personal, and economic damage those measures cause. In this, Sweden has become a “punching bag” – in a strange ideological war zone between those who think it is sacrificing its vulnerable to Mammon or the cross of gold, and the market extremists who’d rather see a more open society.

Interestingly enough, its Scandinavian partners have opted for a more stringent U.S.-style lockdown, where schools, parks and nonessential business are closed. For all the minor differences that exist between Sweden, Denmark and Norway, here we have at least some experimenting as to how effective the measures of pausing society and hibernating the economy will be.

Having a combined population of about 22m (the population of Florida) the Scandinavian countries punch way above their weight – in culture and sports and particularly in the minds of politicians, pundits and social scientists.

For good reason: The Scandinavian countries are weird. They are outliers in almost every aspect of life: they are richer than they ought to be given how large their governments are; they trust their public institutions and their fellow citizens more than any other; they top indices over gender equality, life satisfaction, happiness (together with Finland and Iceland) and human development; they have among the top-10 highest life expectancies in the world. Money spent on healthcare is dwarfed only by the extreme outliers of the U.S. and Switzerland. Their incomes are among the most equally distributed in the world (after transfers; on market incomes they are much like every other European country). They are ruthlessly secular and individualistic to a degree unseen almost anywhere else. They even share mutually understandable languages!

Against that background, it is extraordinary that anyone would think that something operating in Scandinavian countries could be of any guide to the rest of the world. Yet, their countries are praised by capitalists and socialists alike, capturing some element of their respective notions of what a good society is.

So – corona style – let’s check their diverging strategies against each other.

Marathon, Not a Sprint

A number of things make evaluating corona policy responses in real time very imprecise. First, it’s way too early. Lags in economic data reporting mean we won’t know the extent of the damage for some time. GDP figures arrive quarters after the data they report are produced (with revisions years later), so at best we can use unemployment claims that are, comparatively, up-to-date.

Second, there are stages to this pandemic. If one country gets hit harder than another, we’d expect them to show higher numbers at every step of the way during this phase of the pandemic. If the virus must inevitably spread to large sections of society at one stage or another, a higher infection rate may simply mean that a country has gotten there sooner.

Third, radically closing down a society may simply mean a delay in the spread of the infection and a subsequent – second wave – surge of deaths. Postponing death is a good thing, but it seems foolish to celebrate low numbers now when a bigger hit is coming when we again attempt to open our societies.

Keeping those three points in mind, it’s clear that the Swedish shock was initially bigger, with very large numbers of Swedes skiing in the Alps at the time the virus was spreading through northern Italy. Few Norwegians or Danes were, making their policy-makers’ decisions to close borders early on more understandable, aimed at preventing the disease from entering the country.

Because the disease was already widespread in Sweden when closing society became an option, its policymakers received – unfairly – a lot of criticism for letting schools and borders stay open. Because of that larger initial shock, and on advice of its health experts, Sweden moved on to other lines of defense; the cat was out of the bag – no point in making a bad situation worse. (Many of the actions taken by Danish and Norwegian politicians weren’t warranted by scientific expertise or their own health authorities – but leaders, presumably wanting to project strength, took them anyway.)

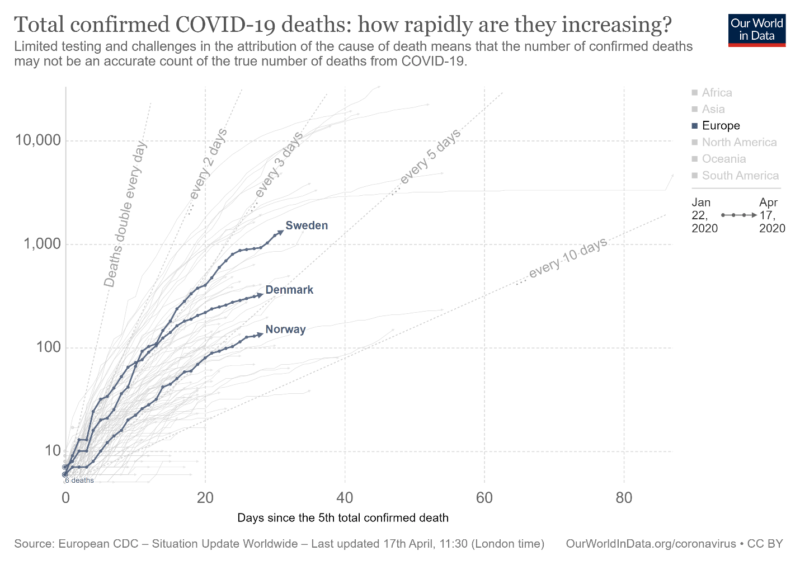

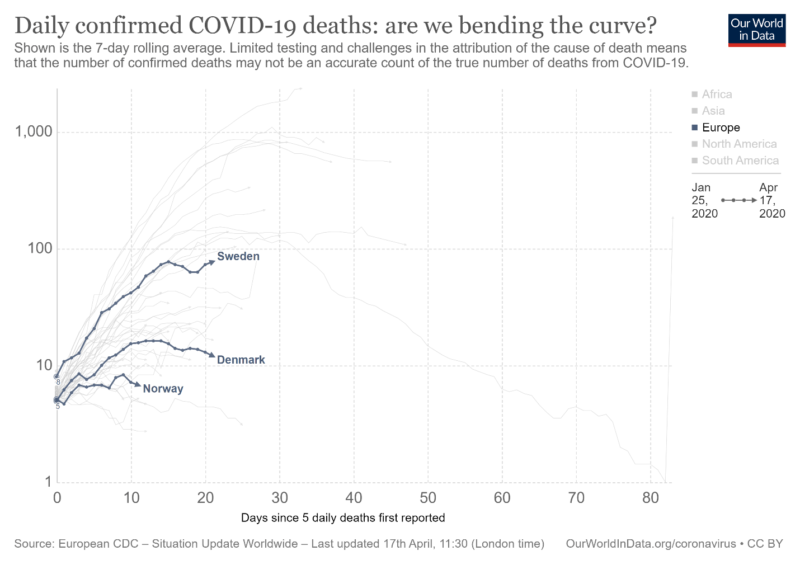

It is therefore not strange that Sweden’s corona numbers are higher, their growth rate faster: perhaps because they are further along the stage, perhaps because the initial shock was greater, perhaps because its Scandinavian neighbors merely postponed the damage to their citizens by locking down society, ensuring greater immediate economic damage. The higher infection rates, death rates, and faster rate of spread reflect this:

Adjusted for population (Sweden has about double the population of either its Scandinavian neighbors) Sweden has more deaths than the U.S. – but with fewer confirmed cases, which roughly tracks a more targeted testing approach.

So far, job losses in relation to deaths give us at least some way to assess whether the measures to protect health by sacrificing commerce have been worth it.

In the table below I describe the three Scandinavian countries in addition to U.S. figures. Besides reporting COVID-19 deaths, in parenthesis I calculate figures that take account of those currently in intensive care. The reason is that I’m trying to assess whether the initial economic damage was “worth” it, “it” in this sense being the increased damage from the virus that a more open approach naturally brings. For this, being in intensive care is sufficiently bad to warrant an inclusion:

| Population | Corona Deaths (Incl. current ICU) | Deaths per 1m population (incl. current ICU) | Job Losses | Job loss-to-deaths ratio(including ICU) | |

| Sweden | 10,338,368 | 1,400 (2,424) | 135(234) | 55,231 (0.99%) | 39 (23) |

| Denmark | 5,822,763 | 336 (429) | 58 (74) | 81,355 (2.8%) | 242 (190) |

| Norway | 5,367,580 | 137 (202) | 25 (38) | 393,211 (14%) | 2,870 (1,947) |

| United States | 329,135,084 | 34,641 (48,101) | 105 (146) | 22,010,000 (13,4%) | 635 (458) |

All figures are publicly available and from official sources (as of April 17). The job loss-to-deaths metric is calculated by dividing jobs lost by the numbers of deaths (reported in parenthesis: those currently in intensive care added to the death toll). For reference, the job losses column also compares job losses with the country’s total labor force, indicating that the unemployment shock to Denmark and Sweden so far has been comparatively mild, where 1-3% of its labor force have lost their jobs during corona, compared to 13-14% of the American and Norwegian labor force.

Note that about 8% of the Norwegian labor force is directly or indirectly involved in the Oil & Gas sector, and as the Saudi-Russia oil price shock already had these companies shedding workers pre-corona, some of the Norwegian job loss count includes jobs that would have been lost anyway. Further, Norway includes furloughed workers in their official statistics, probably exaggerating their numbers.

It is very possible that Sweden, when the dust has settled, emerges from the coronavirus disaster with more deaths per million inhabitants than its Scandinavian neighbors. So far, it looks that way. But we won’t know whether it was worth it until income numbers, unemployment, GDP declines and government debt can be properly assessed, say at the beginning of next year.

Most people agree that a life is worth more than a lost job. Death is permanent; jobs in dynamic markets can re-emerge. This should make us err on the side of more job losses per life – but not infinitely so. Job losses are mostly temporary – but not always and everywhere; once destroyed, not all of them come back. Once corona passes, some businesses won’t spring back up ready to re-employ their shredded workforce.

What’s not clear is how much suffering from one equals the suffering of the other: 20 jobs for each additional life saved? 50? 100? The U.S. is currently running at almost twenty times the Swedish implicit job loss-to-death ratio, well in the hundreds of jobs lost per life lost. Every single one of those jobs lost is a person whose career is put on hold, who’s suddenly wondering how to pay their bills, if a government check will be enough, and if there will be future employment for them once this is over. For some fraction of them, the jobs lost – and perhaps lives lost – will be permanent.

Health matters more than short-term income, but whoever tells you extremities are fooling themselves. “Muh GDP” is as wrong as “you can’t put a price on human life.” Yes, we can – and yes, we should. Anything else is madness.

Sweden has opted for a more open approach, avoided the lockdowns of the U.S. and even its own neighbors. So far, it seems to have paid for this in higher death rates, but a more functioning economy with fewer jobs lost. GDP figures over the next few quarters will tell us more.

For many countries abruptly closing commerce and civic life altogether, it’s still too early based on mortality statistics to say “overreaction.” But that’s what it looks like.