Most Places are Not New York: A Look Through the COVID-19 Data

Dr. Erickson

“A state like New York. . . the state of New York, an entire state, has 19.4 million. In. . . New York City they are really close together. Where I live, in Kern County, we have 900,000 people, it’s one of the biggest counties in California. Everyone is spread out. We drive cars. We don’t ride the subway. . . If they said, doctor, how would you open up New York and how would you open up California. Would you have a same or a different strategy?

Dr. Wittkowski

“. . . [I]f it’s closely populated like New York, you can get very high spikes. In a country that is not very closely populated you would never have such a high spike because it takes more time for the virus to travel from one place to the next. So I think there is no reason anywhere in the United States to say ‘we need to continue with this second prohibition.’”

As of writing today, we have observed for two consecutive days U.S. death tolls that are at their lowest since March. Not to raise our hopes, Dr. Anthony Fauci has advised that we should expect to be homeschooling our children in the fall. Are conditions so bad that we will not be past the peak of the curve by the end of the month? And even if we are not, allowing the spread to occur among younger students has been precisely the opposite approach than taken by Germany and Sweden, countries that have fared relatively well over the last two months. So which is it? Are we in a year-long crisis where even spread among children is dangerous, or have we reached a point where voluntary precautions are enough to allow a return to normalcy?

Here at AIER we have documented that most of the early models over predicted the number of deaths by a magnitude of greater than 10. As Yogi Bera once said, “It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.” In this spirit, a recent article in The Spectator makes the plea that “It is data, not modeling that we need now.” We have plenty of data. It’s just a matter of making good use of that data.

Following The Spectator’s suggestion, I reviewed county level COVID-19 data from Johns Hopkins, perhaps shedding light on conflicting opinions of Dr. Fauci, representing the disposition of many providing advice to policymakers, on one hand, and Nobel Laureate Michael Levitt, Professor Johan Giesecke, Dr. Knut Wittkowski and Dr. David Katz who suggest that we allow the virus to spread while sheltering the vulnerable.

Nearly two weeks have passed since the start of reopening of states across the U.S.. COVID-19 continues to spread, but there are reasons to be hopeful. Most of the United States has been able to avoid the overload of local medical systems experienced in New York and other Northeastern states where the virus has spread. New York City has been the epitome of conditions to avoid in this regard.

The virus arrived early in New York and had considerable time to spread across the population. Unaccustomed to pandemic and guided by political leadership, individuals were slow to adjust their daily behavior. In most places, the situation might not have turned sour so quickly, but heavy use of public transit and the nature of living within America’s most densely populated city promoted a fast spread. Before the end of April, researchers estimated that greater than 20% of New Yorkers had contracted the coronavirus, as compared to around 5% of Californians in Los Angeles and Santa Clara Counties.

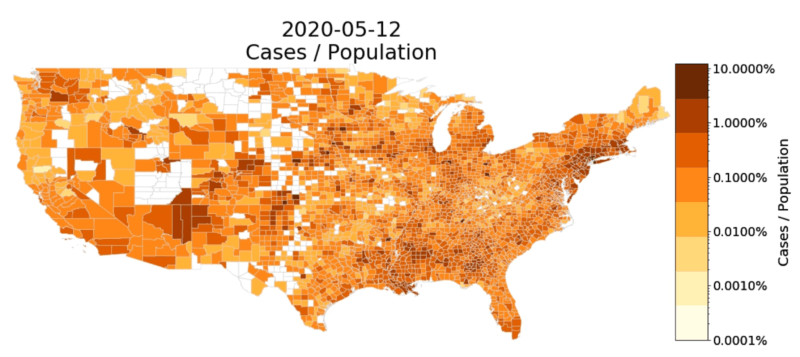

Thankfully, we have not yet seen anything comparable to the spread in New York. Most American cities are not comparable to New York City. And much of the U.S. is rural or at least not very densely populated. With less interactions per person in these areas, the rate of spread tends to be much lower. Thus, many counties in the middle of the U.S. have not recorded even a single death involving COVID-19 as of May 12, the most recent date for which Johns Hopkins provides data.

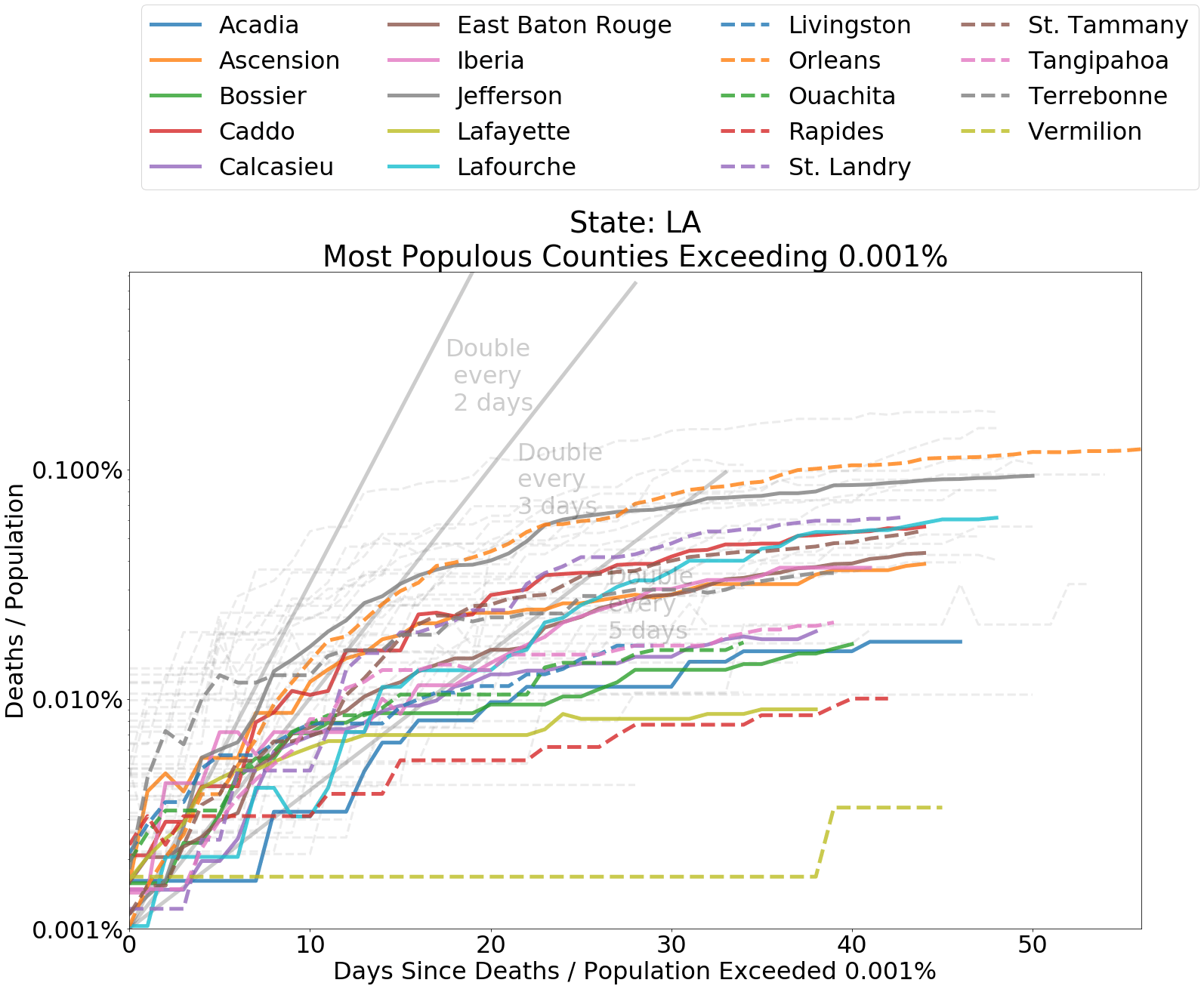

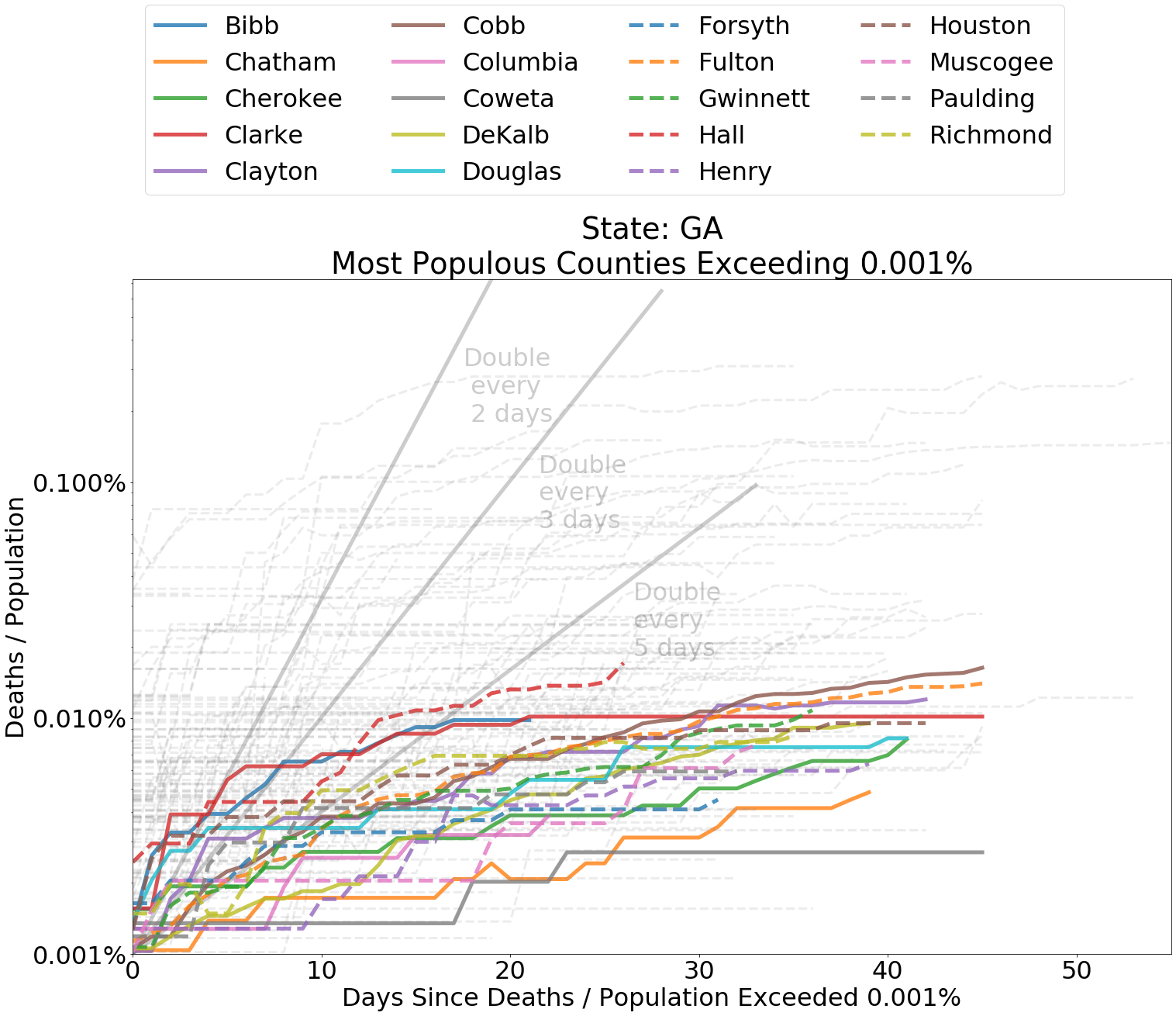

While there have been other local spreads, such as those in southwestern Georgia and across Louisiana, overall the rate of spread has been slow. Deaths from COVID-19 as a portion of the population in Georgia’s most populous counties has been limited in comparison to some rural southwest counties in the state. These are the exceptions.

In many areas across the U.S, residents have had time to internalize norms of social distancing and actively maintain standards of hygiene that limit the chance of contracting the virus. Those who are vulnerable have had more time to develop strategies to protect themselves. The increase in cases in many of the areas where spread occurred relatively slowly has not been accompanied by an increase in the level of fatalities comparable to the northeast. Probably another month or more will need to pass before one can express confident judgment. Still, this is an encouraging sign that precautions to protect the vulnerable have been effective.

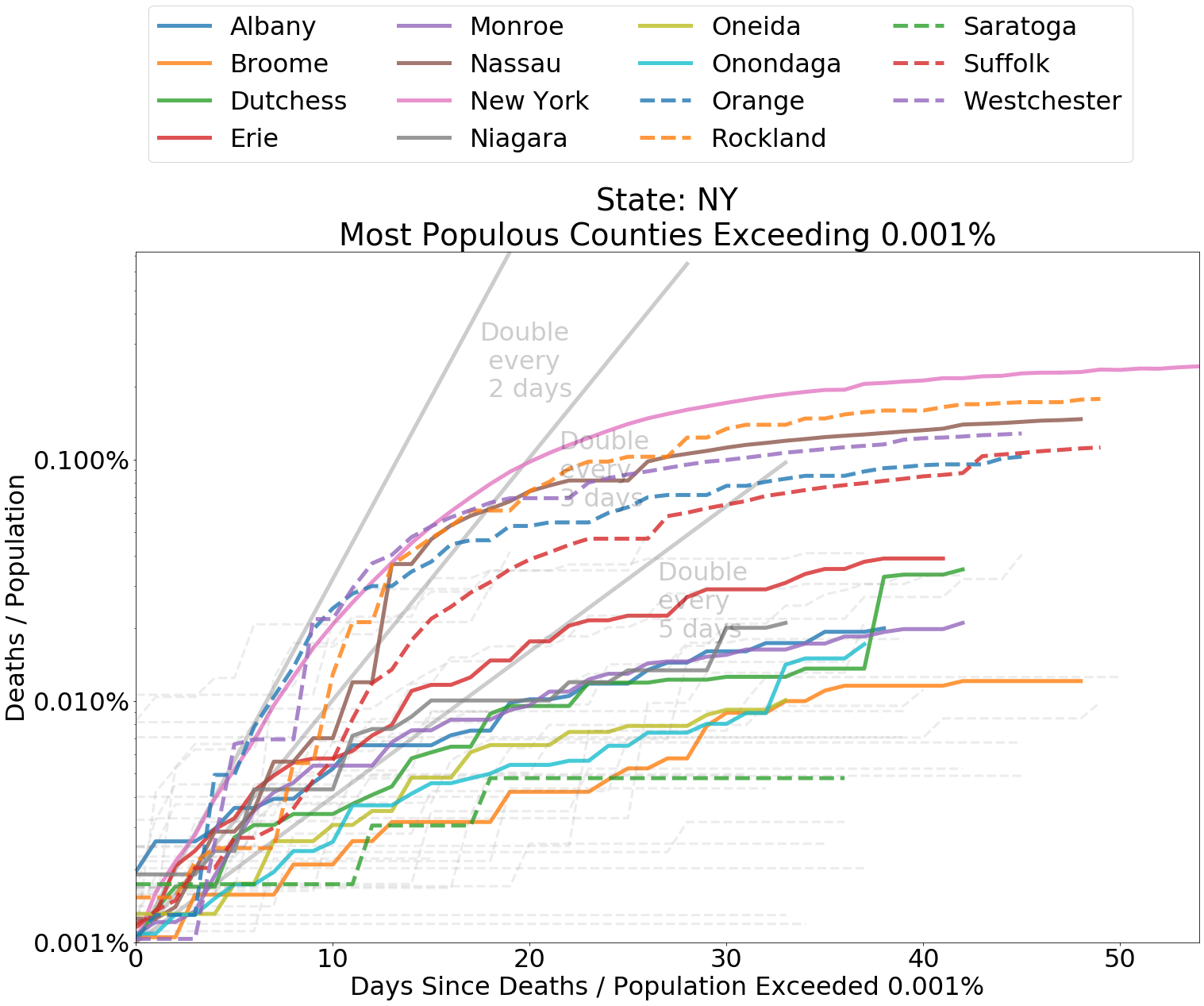

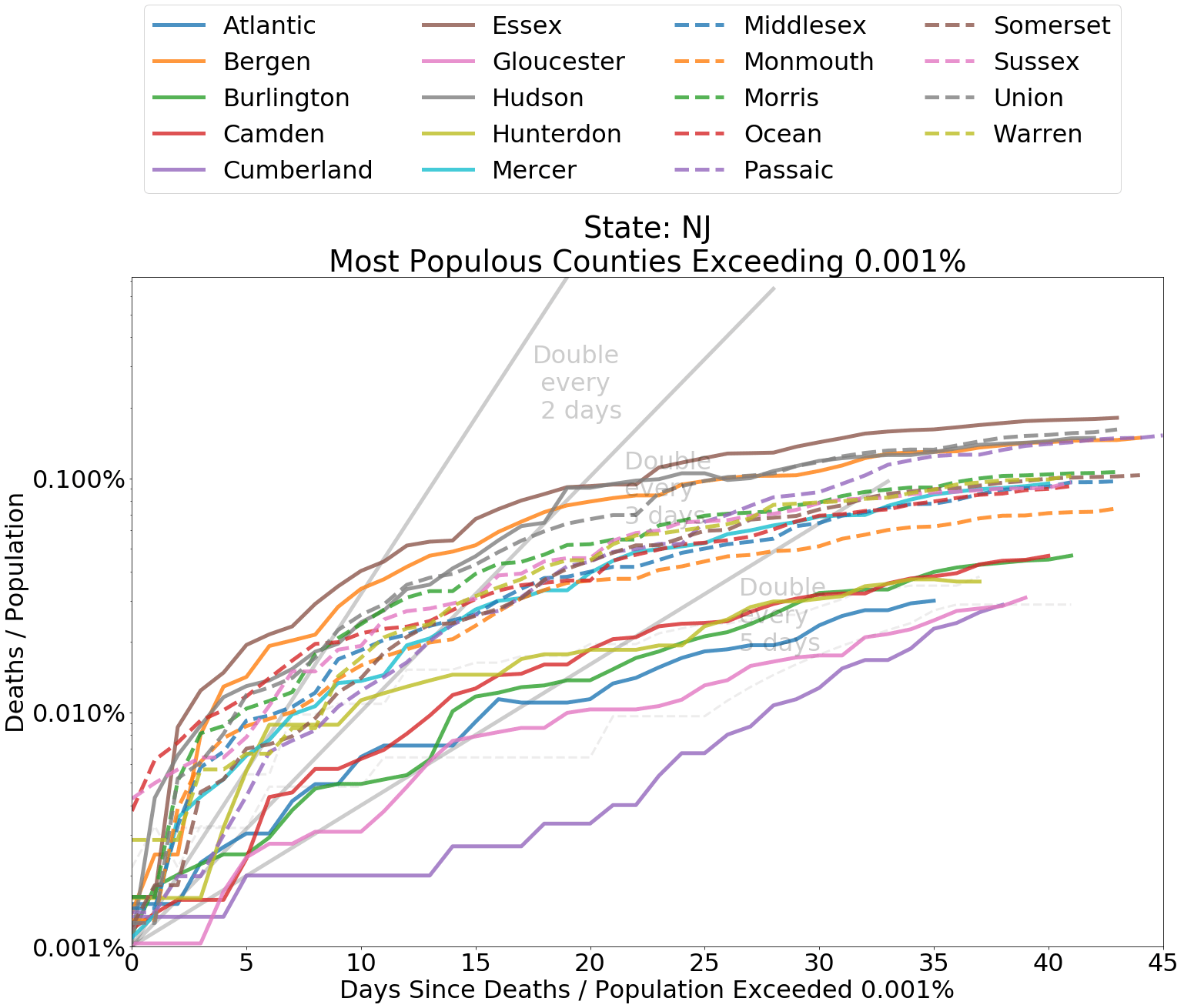

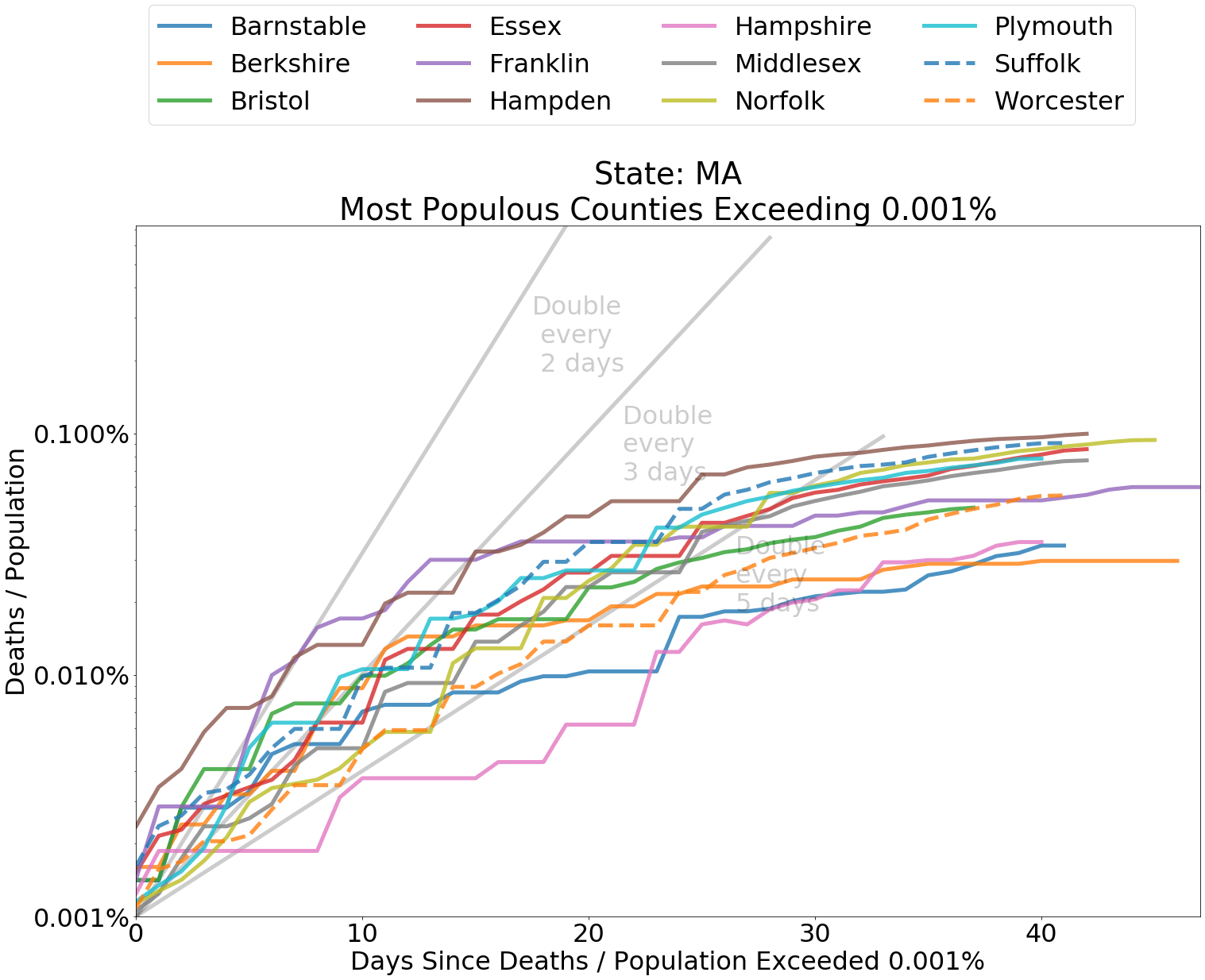

Comparing the Evolution of Spread

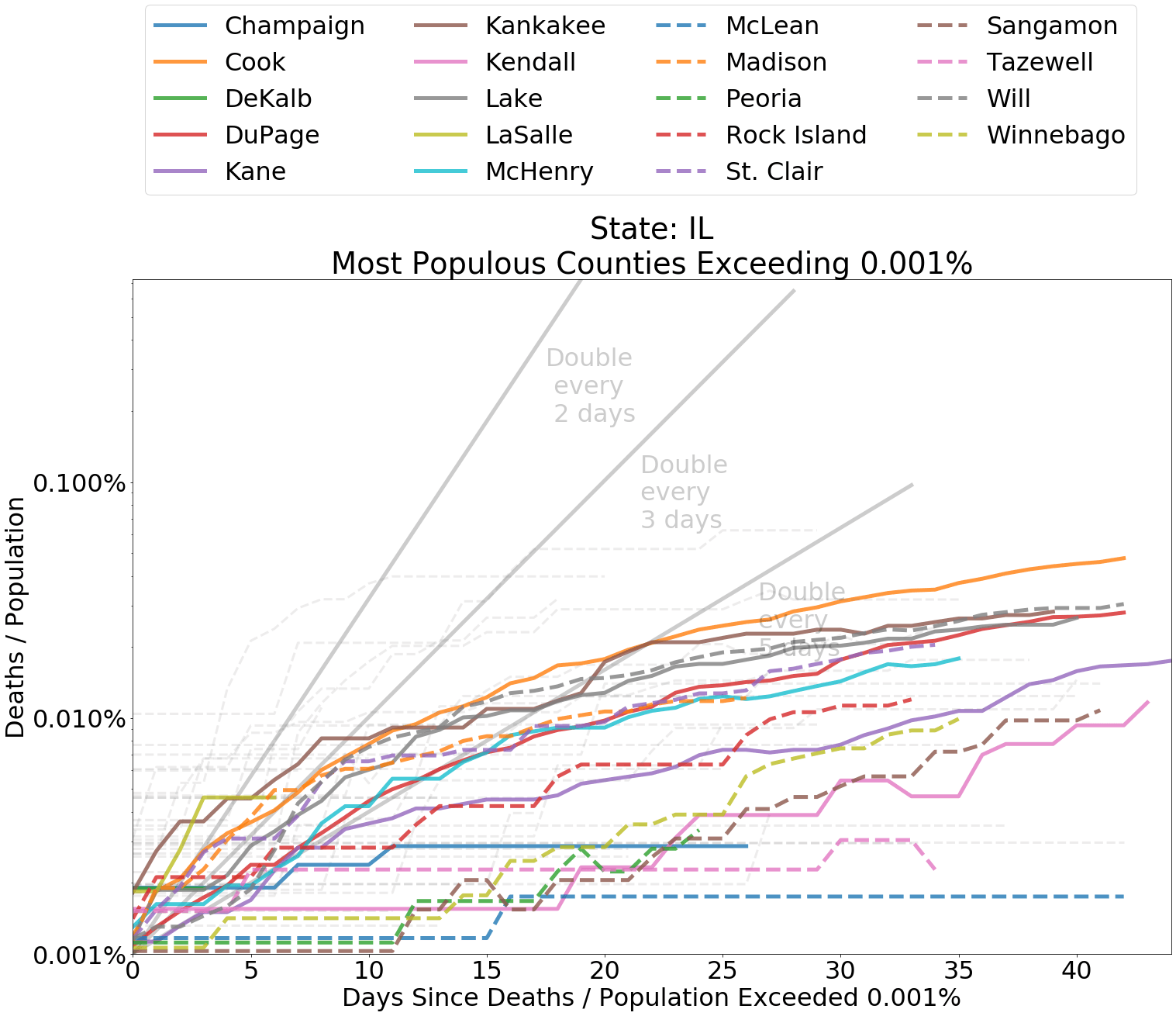

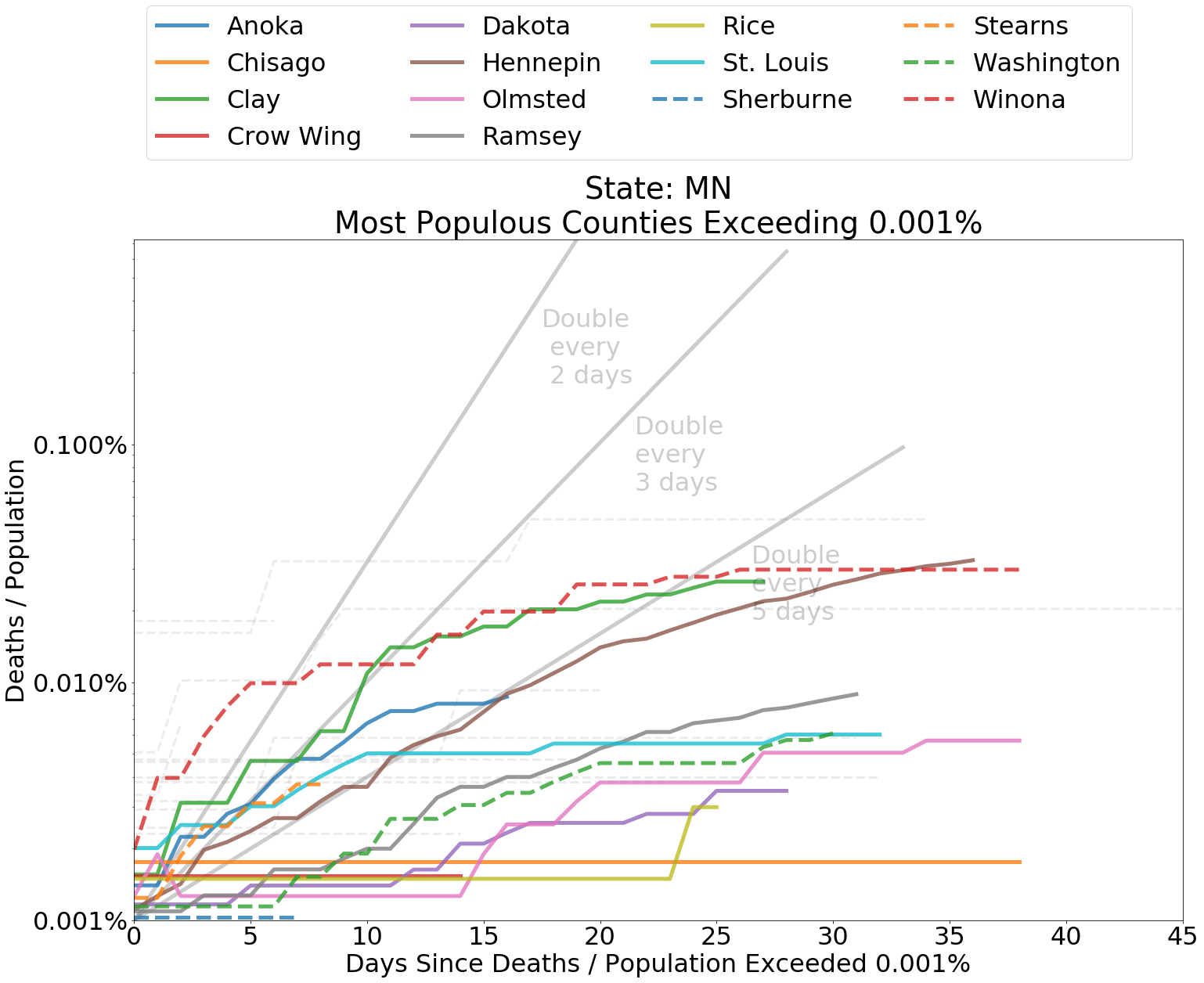

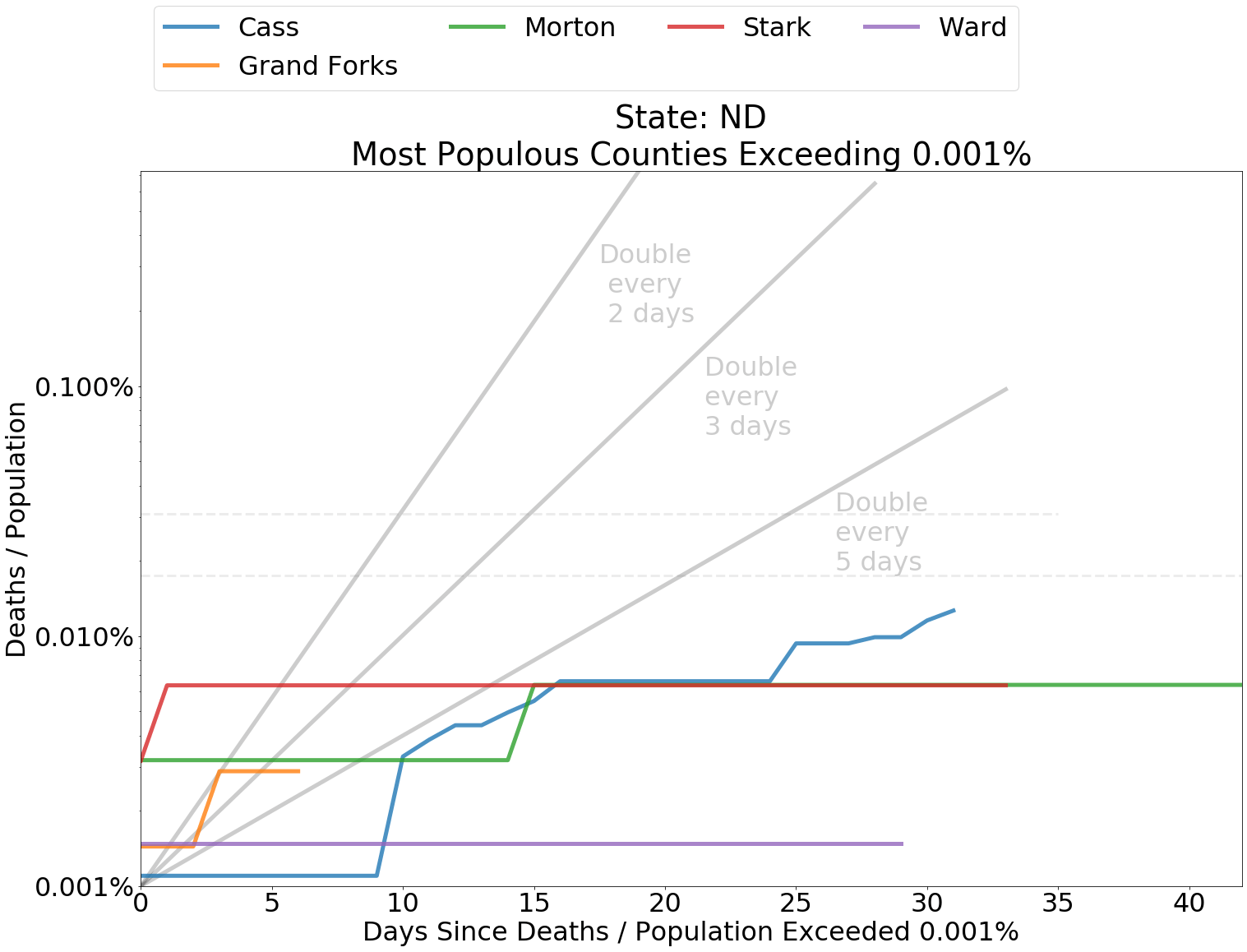

Below I have included graphs of counties by state, comparing the deaths from COVID-19 within each county as a proportion of county population. It is helpful to judge the spread according to the slope of the curves. The grey lines indicate a doubling of deaths every 2, 3, or 5 days from the first day that at least 0.0001 percent of the population had died from COVID-19. Since the data is normalized by population, it is also fair to compare curve levels.

Whether or not you are concerned about overcounting, as indicated by this CDC measure, it is the rate of spread that concerns us in regard to the capacity of the medical system. A persistent doubling of deaths, say, every two days or less indicates a system that is being incapacitated by the coronavirus. Most counties have experienced a doubling of deaths from coronavirus about every five days or longer. Spread in nearly every region outside of the Northeast has been relatively tame.

Compared to other states, New York and neighboring states experienced high death rates in the earliest days of the spread. These represent worst case outcomes to compare other data against. Many other states, especially in the Midwest and the West, have not experienced high rates of increase in deaths relating to COVID-19. These states have flatter curves.

In general, the Midwest has fared quite well. The Minneapolis and St. Paul metro-region is no exception. The top three most populous counties in Minnesota – Dakota, Hennepin, and Ramsey – reside within this region. All have managed to contain the spread. In Hennepin, the total number of deaths from the coronavirus has tended to double, at most, once every five days. Dakota and Ramsey have fared even better.

In Cook County, Illinois, home to the Windy City of Chicago, the rate of increase in cases and deaths has moderated, though officials are still uneasy about lifting restrictions. Overall, the medical system in Illinois has successfully weathered the pandemic. In my own state of North Dakota, the increase in fatalities from coronavirus has been even more modest. Health officials here have avidly traced transmission of the disease to ensure that it does not bring further disruption. The relatively slow spread in these states is representative of outcomes in many other regions across the country.

Even in regions that have seen a modest increase in spread of coronavirus, the spread has been just that. Modest. Medical systems across the Southwest are not overwhelmed and are largely expected to be able to handle any increase in patients from coronavirus. Michigan and Louisiana have suffered the worst spread outside of the region of spread with New York as its epicenter. There, estimated demand on ICUs exceeded capacity at the peak and have since fallen below capacity. In short, no region in the U.S. is currently experiencing a New York-like crisis.

New York and Nearby States

States in Other Regions

Counties that rank in the top 20 most populous within each state and have measure of “Deaths / Population” ≥ 0.001% for COVID-19 related deaths are shown in color. Counties outside of the top 20 are represented with grey dashed lines. If a county does not appear on the map, “Deaths / Population” in that county is less than .001%.

America Post-Lockdown

Given the continual stream of bad news that has bombarded the collective American consciousness over the last two months, it might be difficult to believe that the situation regarding the spread of COVID-19 is not dire thanks in large part to the development of concern among the citizenry and a sense of corporate responsibility. Two weeks after many states have reopened, the new deaths and even the number of new cases across the country are still on the downtrend. While this is no time to throw caution to the wind, data seems to be a sign that our voluntary measures are succeeding.

Perhaps it is enough. Dr. Knut Wittowski, who was recently interviewed by AIER’s president, Edward Stringham, advocates allowing for the coronavirus to spread among the healthy. A faster spread will decrease the amount of time the vulnerable are at risk and, therefore, need to shelter.

The strategy worked in Sweden, which has fared about as well or better in terms of the percent of lives lost from COVID-19 than many of its neighbors that did lockdown. The difference in the rate of spread of the virus in areas distant from New York suggest that the social distancing and hygienic measures have been effective. A diverse physical and social geography in the U.S. has also ensured that spread across most of the country has hardly been comparable to spread in New York.

If Americans let down their guard, we could see a second outbreak. While not outside of the realm of possibility, the slow rate of spread in states that did not issue stay-at-home-orders is an encouraging sign that COVID-19 is not ushering in an apocalypse. Living in one of these states, I notice that even here people are especially careful. Aside from a limited number of establishments on Friday and Saturday evenings, the town is still quiet. Most people are staying home and, if they do go out, only ordering takeout. Most stores and restaurants that are open require that parties maintain social distancing protocol. In short, even in rural states, we have adapted.

It is a good thing that we have found voluntary means to approach the pandemic. Unemployment levels have pushed past 20%. Every day the lockdown continues is another nail in the coffin for struggling American businesses and employees of those businesses. A collapse in productivity has spelled the loss of livelihoods. And with this loss, we will see more poverty. Tens of millions of Americans, and their families, are experiencing real suffering due the economic fallout that is accompanying the lockdown. Layoffs have had a disproportionate effect on employment of workers with the lowest incomes. To add to the difficulty, labor force participation has fallen by over 3 percent. So much for the V-shaped recovery.

We cannot move on until much of the world has also moved on from this crisis. Disruption of supply chains around the world has shown us how closely bound together is each other’s fate. Sweden may have avoided a shutdown, but it has not avoided an economic downturn. Economic activity in one country is dependent upon economic activity of its trading partners. Trade makes us rich because it allows each of us to provide value and offer it to others in the market. If half of the world is in lockdown, we are all poorer for it.

Perhaps this has been the cost of learning. Before the recent shutdown, contagious disease had passed from collective memory of America and much of the rest of the world. Yet the spread of a pathogen like COVID-19 is not even a once in a century event. And at least as dangerous as COVID-19, a contagion of fear has swept the globe. We lacked an obvious contingency plan for protecting those vulnerable to disease, one that might guide us through troubled times.

Our problem was not that we did not shut down soon enough. As the experience of Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan suggest, the shutdown of the economy is a sign of being ill-prepared. Our problem was that we did not take the possibility of pandemic seriously. As we sensed the seriousness of the situation, we were not ready to take precaution appropriate to protect ourselves and those we love. Having learned, we need not fear.