Micromanaged Business Reopenings Could Cause More Harm

Depending on who you ask about the reopening of businesses beginning across the United States this week, we may have finally reached the light at the end of a self-imposed tunnel or be on the brink of a reckless leap into the abyss. Where both visions likely go wrong is their assumption of a climactic moment, where some are proven right and some wrong, and we turn the page on the COVID-19 pandemic that’s dominated our lives like few other events in recent memory.

Those seeking closure as America reopens will likely be disappointed. Judging by most states’ specific plans, we’re in for an arduous, confusing process with enough moving parts to provide the cover necessary for nobody to have to rethink much of anything. How appropriate that while encouraging this bitter cacophony these elaborate attempts at the illusion of control crowd out the one freely cooperative activity that cuts across even the most intractable lines–good old- fashioned commerce.

Make America Hayekian

The forced closures of businesses and “shelter in place” orders issued by almost every U.S. state hit the economy like a freight train in late March and early April. Now, the consensus across levels of government appears to be a meticulous and micromanaged rollback process, akin to the careful investigation that might take place after a literal trainwreck.

A drawn-out reopening process actively managed by state regulators rather than communities or businesses themselves suggests the scope for even more damage to an economy that already saw unemployment climb from 4 percent in March to over 14 percent in April.

During his brief staring contest with the 2020 Presidential elections, Michigan congressman Justin Amash hit the nail on the head of what regulators are getting wrong:

Epidemiologists cannot know the specific actions of each individual in a community. This kind of knowledge is not knowable to any scientist. The top mistake being made by state governments is their imposing uniform rules that limit the use of local knowledge to fight the virus.

Responses in some circles casting Amash as a Luddite bumpkin failing to see the scientific big picture instead showed their own naiveté in the face of a modern complex society. The reality of supply chains, overextended households, the quirks of local communities, and dozens of other factors mean economic activity will likely lag far behind the rates that regulatory hand-pickers intend.

Whether managed step-by-step or allowed to happen all at once, U.S. businesses will be reopening their doors to an entirely new reality. The process of finding a sustainable and prosperous normal will be messy and involve too much suffering even at its best. But regulations meant to ease the country back to work are more likely to prevent businesses from engaging in an informative discovery process through competition and making the small intuitive adjustments impossible to implement from the top down. Most states, including AIER’s home of Massachusetts, appear to be heading down this dangerous road.

Bay State Blues

The plan put forward by Massachusetts, with its decades-long history of overcooked regulatory schemes, unsurprisingly reveals an understanding of markets and governments’ role directly at odds with at least a few of its residents.

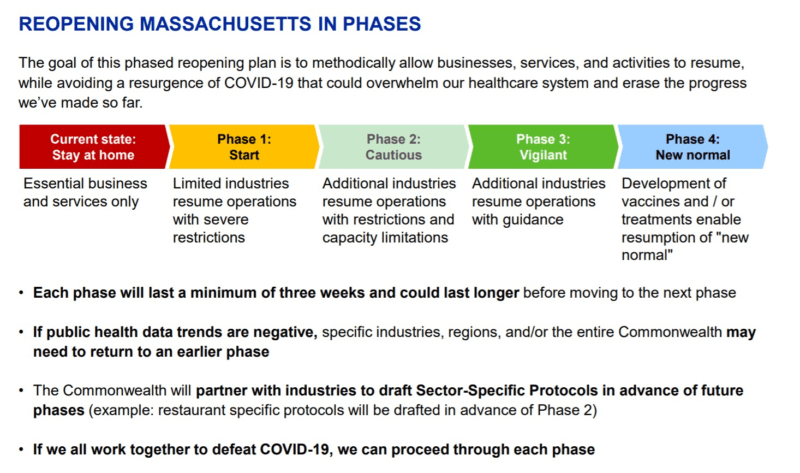

The authors of a May 18, 2020 PowerPoint document entitled “Reopening Massachusetts” clearly wanted to demonstrate to state residents just how careful they intended to be while letting the state get back to business. As the screenshot below shows, the state’s plan revolves around a multi-phase timeline, with different kinds of businesses allowed to begin the steps at different times and many opportunities for the state to hit the breaks in the event of increased observed COVID-19 transmission:

State planners betray at least some awareness of how little information they have to work with when they try to jump from the knowledge-problem frying pan into the rent-seeking fire, looking to “partner with industries to draft Sector-Specfic Protocols in advance of future phases.” No doubt these future protocols will favor the large and well-connected businesses invited to such “partnering” sessions.

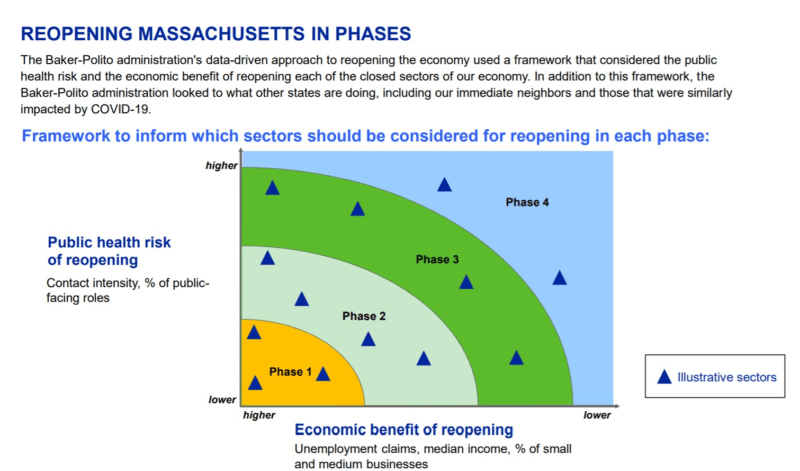

What objective scientific criteria does the state employ when they decide which business will begin the process sooner rather than later? The document falls somewhere short of gravitas when representing the process on a graph in which “public health risk of reopening” is plotted against “economic benefit of reopening.”

In attempting to convey that the adults in the room have spent a long time thinking about this difficult issue, Massachusetts instead exposes just how little regulators’ blunt instruments can possibly add.

Many other states, while piling on details in a manner similar to Massachusetts, vary across several dimensions in approach. Pennsylvania, whose initial stay-at-home orders varied by county (potentially an improvement over statewide scheduling), plans a similar approach when reopening. Other states, such as Wisconsin by court edict and Georgia by regulatory preference, appear to be opening faster and more broadly than average. But as a whole state governments appear poised to do more harm than necessary in ending a work stoppage they created.

Libertarian Half-Measures

This process-oriented way of thinking about markets and competition is second nature to many libertarians, but as reaction to Amash’s tweet indicates, it is not how the majority of people nor most regulators are used to thinking. I fear that this disconnect is forgotten by both sides when the only free-market pushback anyone hears is “open everything immediately.”

This may be ideologically honest and consistent, but save the occasional state Supreme Court judge, is unlikely to be heard by government while this crisis is underway. The value of individuals having even limited freedom and flexibility to make decisions responsive to the knowledge only they possess is already visible in the first stage of this crisis.

In theory “voluntary” and “forced” are absolute and distinct ideas. In a real world where many things happen at once, enforcement is costly, and no two individuals are the same, those lines can easily blur. Forced business closures in response to COVID-19 fall on visible targets and are relatively easy for regulators to enforce. It would be very difficult for most businesses to make a couple of sales to customers most needing their products or services without bearing fixed startup costs or simply being caught. Regulators likely stomped out this type of local knowledge when they forced many businesses closed.

Individuals and families, through “shelter in place” orders not to mention closed businesses, have borne very large costs as well, whether or not one deems those costs “worth it” in stopping the virus’ spread. But beyond the worst anecdotes and literal readings of rules, most of us have moved about in a manner that, while restricted, involves some degree of personal choice.

Though I’ve certainly reduced my trips out through some combination of risk of law enforcement reprisal, social pressure, and belief that it would slow the virus’ spread, the specific times when I have left the house have been up to me. If my trips out were reduced by three quarters, I likely have a good deal of discretion to make my remaining trips out have value to me in the upper quartile.

Business owners, during forced closures or micro-managed reopenings, have no such opportunity for breathing room through their own discretion. State governments who insist on phased reopenings should instead look to rules with more room for interpretation or, in a counterintuitive manner, can’t be perfectly enforced. This is nobody’s idea of a perfect solution or one that makes good social media copy. But it would likely reduce economic damage from managed reopenings just underway.

We will have years to make the case that shutdowns were the wrong call, or that government epidemiological models were biased toward disaster, among dozens of other individual or systemic catastrophes. We might spend more time considering this and other incremental steps that could help people now during these uncertain next few months.