Global Money Supply Growth and the Great Inflation Getaway

It has become evident over the last few months that the stock market and the economy can dance to very different tunes. During a period of just over three months, the Nasdaq 100 not only recovered from a 32.5% decline, as the worst fears emerged about the global pandemic – which tragically continues to infect more people each day – but took out its all-time-high from February 2020.

Meanwhile, according to Nouriel Roubini, the ‘Coronavirus pandemic has delivered the fastest, deepest economic shock in history,’ whilst the International Labour Organisation estimates that working hours, globally, declined by around 10.7% in Q2, 2020, compared to Q4, 2019. That is equivalent to 305 million full-time jobs lost.

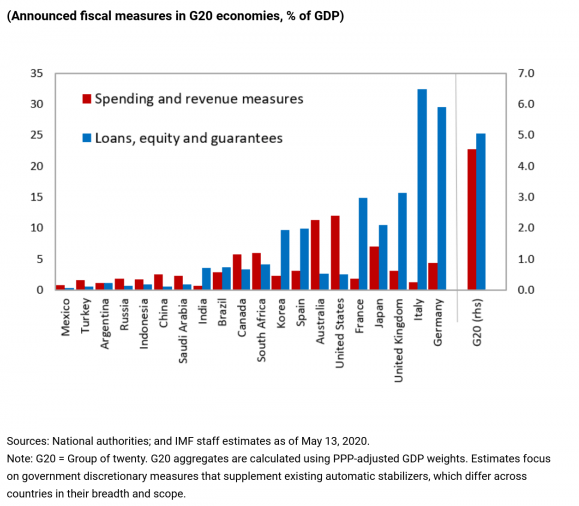

I believe the principal reason for the stock market recovery is the enormous fiscal and monetary response from governments and central banks. The tally as at May 20th, calculated by the IMF, puts the global total at $9trln. In Europe this stimulus has principally taken the form of loans, equity and guarantees. In the US, by contrast, the direct fiscal spigot has been opened wide: –

Money Supply and GDP

During the inflationary era of the 1960’s, 70’s and 80’s, so called ‘Monetarist Economists,’ led by Milton Friedman, gained prominence, as developed nations wrestled with the inflationary scourge. Inflation destabilised developed nation economies despite the strictures of the Bretton Woods Agreement and eventually hastened the Gold-Exchange Standard’s complete collapse. In his 1970 publication, The Counter-Revolution in Monetary Theory, Freidman argued that: –

‘Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon in the sense that it is and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output.’

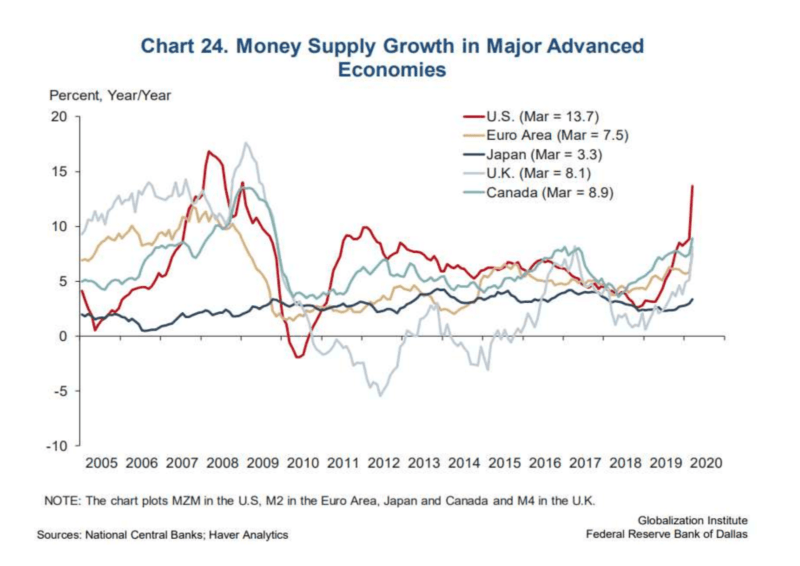

The inflation, to which Friedman alludes, can take the form of an increase in the price of goods, services or even assets. The recent crisis response of central banks and governments in some ways mirrors that of 2008/2009. The results are patently evident in the money supply data: –

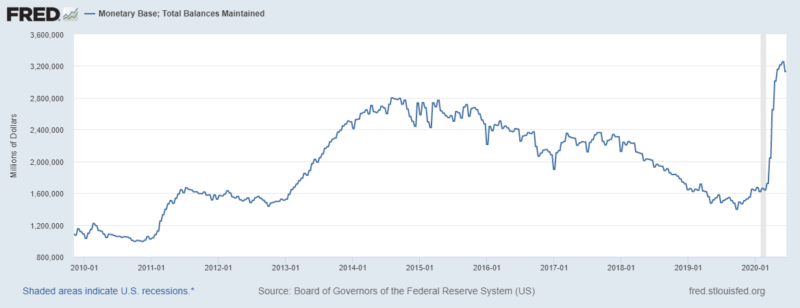

In money supply terms, the global response is not yet quite comparable to that of the financial crisis; however, the US response has been both swift and exceptional. The chart below shows the rapid increase in total US money balances: –

Monitoring the quantity of money in an economic system is important because money rarely stands still; once deposited at the bank it is quickly put to work. On this occasion I expect a substantial proportion of the sharp increase in bank cash balances to be invested in liquid markets rather than long-term loans. This angst-induced rise in sight deposits is reflected in a rise in the nations’ liquidity preference. It would be most incautious of bankers to borrow too aggressively, short-term, in order to lend long-term.

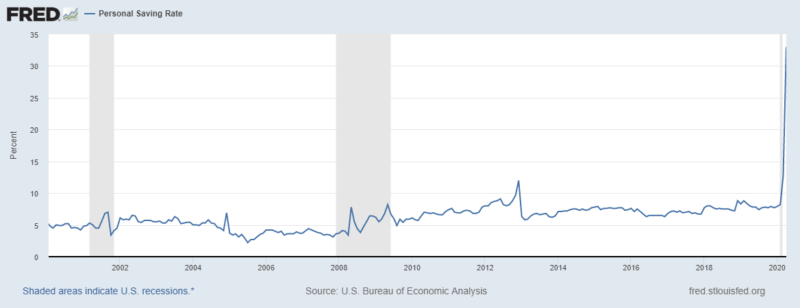

In the current environment, with unemployment surging – in the US it reached 14.7% in April – and expectations of an imminent end to the generous welfare of the past few months, individuals and households, which can afford to choose, have chosen to save rather than spend their state-decreed windfall. At some point in the near future they may need to make a swift withdrawal: –

Rising global uncertainty has seen the velocity of money collapse further; nonetheless, lower interest rates and lower bond yields both favour stocks. Where else can one eke out an acceptable return confident in the knowledge that you can liquidate your investment with relative ease?

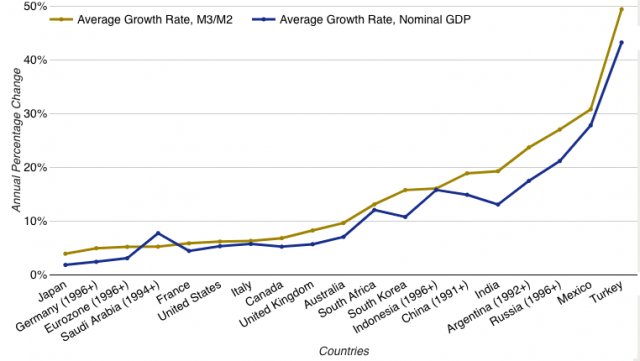

From a monetary perspective there is a fairly consistent long-term relationship between the growth in money supply and growth in nominal GDP. The chart below shows this relationship across a wide range of both developed and emerging economies: –

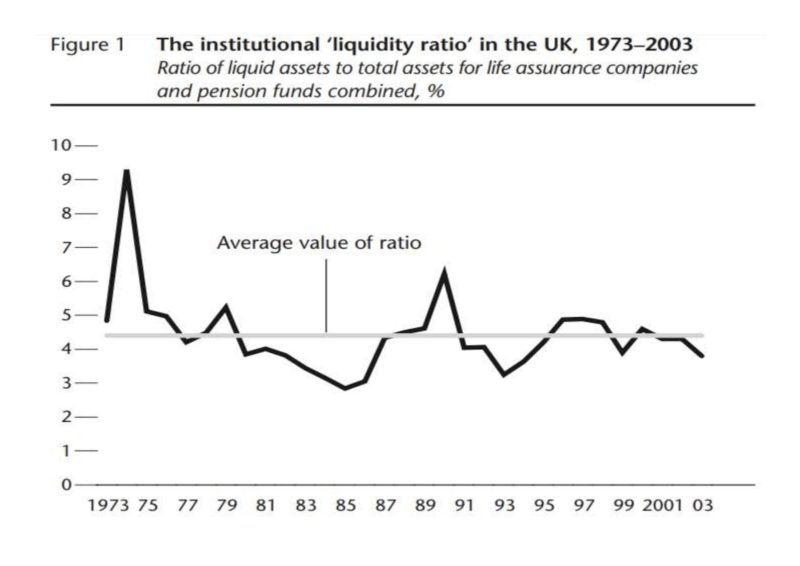

Whilst the stock market and the economy are currently dancing to different tunes, there also exists a long-term relationship between monetary growth and the performance of stocks. In aggregate, corporate profits are linked to economic growth and economic growth is correlated to the size of the monetary base. In the shorter term there can be significant divergence, but, for professional money managers, aside from those which operate money-market funds, there has never been a great incentive to hold significant cash balances. The chart below, taken from Money and Asset Prices in Boom and Bust – Tim Congdon – IEA – 2005, shows the Institutional Liquidity Ratio in the UK between 1973 and 2003: –

This chart shows the percentage of cash held by insurance companies and pension funds over the 30 years to 2003. In the depths of the first oil crisis this ‘cash reserve’ reached a precautionary 9%. During the boom preceding the 1987 stock market crash ‘cash liquidity’ slid to a little more than 2.5%. The 30-year average was 4.5%.

Since 2003 interest rates have fallen substantially, making cash an even less attractive asset for money managers to hold; however, liquidity ratios (often imposed by government regulators) remain a prudential pillar of sound asset management. They are designed to insure solvency. It is unlikely that the average liquidity ratio has fallen significantly over the last 17 years.

The key insight from the chart above is that, as the size of the monetary base rises, the amount of cash available to institutional investors to allocate to asset markets also increases. If the liquidity ratio remains stable, cash should flow into assets which offer a higher expected return. With many government bonds offering negative yields, even non-yielding assets such as gold or growth stocks, which pay no dividends – and, in many cases, have no earnings – start to look alluringly attractive.

With global uncertainty hitting generational highs, the ratio of cash to other assets may increase, but with US M2 money supply growing 18% in April and 23% in May – and the Eurozone M3 not far behind at 8.2% in April and 8.9% in May – it is not surprising that stock markets appear to be defying gravity.

Bubble Logic

If, as Keynes is rumoured to have said, ‘The stock market can remain irrational longer than I can remain solvent,’ then we should not rule out the possibility that we may be embarking on what Ludwig von Mises referred to as a ‘crack-up boom.’ For the stock market, which many economy watchers think should be fretting about the current gloom, conditions are, in fact, ripe for a bubble.

As with all irrational periods, it is important to be on the lookout for signs of danger. Here are a few observations: –

- Bubbles defy gravity; they pay no heed to economic logic.

- Monetary easing often inflates a bubble, but once the bubble is underway the initial phase of monetary or fiscal tightening does little to stem rise in speculation.

- Events, rather than central banks, often bring bubbles to an abrupt halt. A failure, a fraud, a default are much more common culprits than the gentle nudging of central bankers.

- When a bubble is inflating, valuations are irrelevant. Once it bursts, a sound assessment of value may be all that saves an investor from ruin.

Trickle down inflation

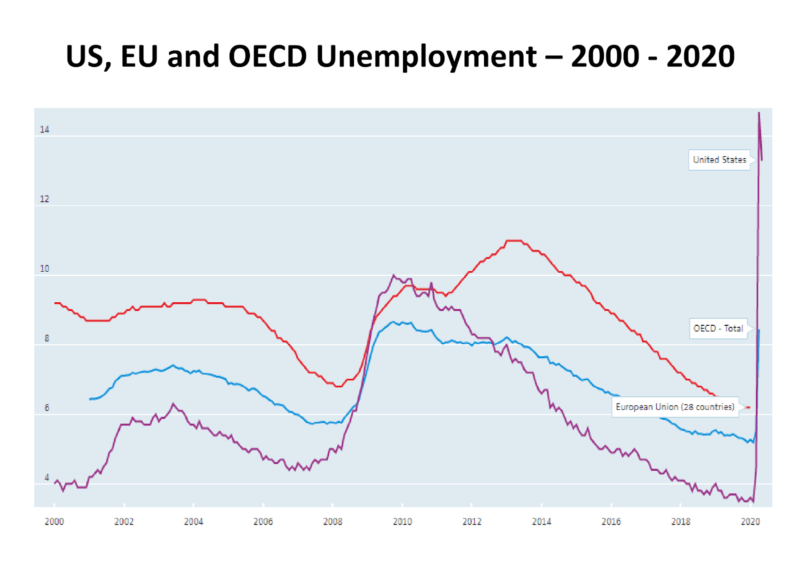

With US unemployment hitting levels not seen since the Great Depression and the harmonised OECD average at its highest in two decades, it seems unlikely that consumer spending will rebound too rapidly. However, if the stock market booms, the asset rich will feel richer, and their spending will trickle down. Meanwhile, bottlenecks and global ‘re-shoring,’ to strengthen supply-chains, will render a number of goods relatively scarce. A modest increase in demand could spark a significant increase in the consumer price level.

Here is a chart of US, EU and OECD unemployment since 2000: –

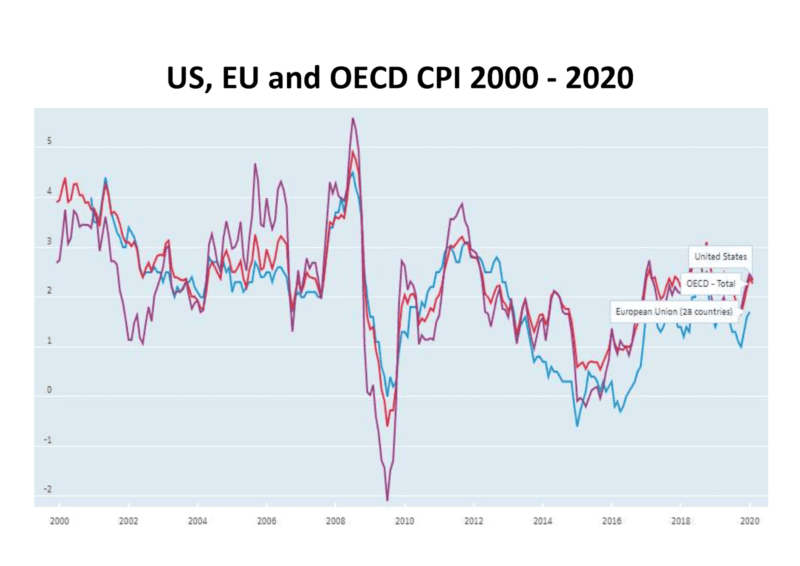

For good measure – and despite the rise in unemployment – here is the CPI Index over the same period: –

What will central bankers do when confronted with high unemployment and rising prices? I would argue that we have entered a new era of ‘fiscal dominance.’ Central banks are only notionally independent. I have suggested previously that their principle raison d’etre is to help finance the obligations of their governments. Managing the currency, setting domestic interest rates and maintaining full employment are supplemental.

I suspect, fearful of repeating the mistakes made by the Bank of Japan, that once the inflation genie is finally out of the bottle, central bankers will forsake the hard-learned lessons of the 1970’s and 1980’s and allow inflation to conjure away the fiscal deficits of their governments at the expense of pensioners and other long-term investors. The chart above of CPI inflation remains inconclusive, but a structural shift towards higher prices for goods and services may already be underway.

Conclusions

Money supply growth has accelerated rapidly in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic; however, in the US it was already rising fast and may have been instrumental in pushing US stocks to new highs in 2019 and early 2020. Now, after a significant correction and the addition of some $9trln of monetary and fiscal liquidity, many stock markets, but especially the technology heavy Nasdaq 100, have regained much of their former composure.

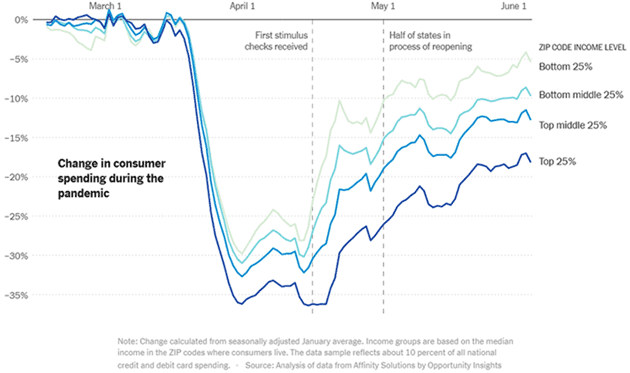

The COVID pandemic still rages and fears of a second wave of infection continue to colour the policy decisions of governments globally. Further fiscal and monetary stimulus should be anticipated with a focus on employment. Household savings have risen dramatically in response to a large increase in unemployment. As the chart below reveals, ballooning cash balances, principally from higher income individuals, are, at least partially, being recycled by the banks. This liquidity is fuelling investment which may trigger an irrational bubble in stocks, followed, as higher income discretionary spending returns to normal, by a more general inflationary boom: –

Consumer spending during the lockdown has focused on needs rather than wants, but when the new normal returns, there will be fewer outlets for expenditure and the cost of provision of those services will, inevitably, rise. Restaurants, for example, will be fewer and will charge higher prices to compensate for lower capacity due to social distancing.

With a US election in November, it seems unlikely that the Federal Reserve will take away the punch bowl anytime soon. US fiscal policy has been the most aggressive among developed nations. US stocks have led Europe and Asia, but Eurozone governments have also embarked on policies which will substantially increase their monetary base. Global economies are on their knees, and stocks are near their highs.

Maintenance of the level of employment rather than inflation has become the focus of official policy everywhere. Stimulus will continue until employment is restored to its pre-crisis level and there remains a colossal debt overhang to temper inflationary tendencies, but there is a real and present danger that, in the process of returning the economy to full-employment, consumer price inflation will get away.