GameStop, Bitcoin, and the Federal Debt

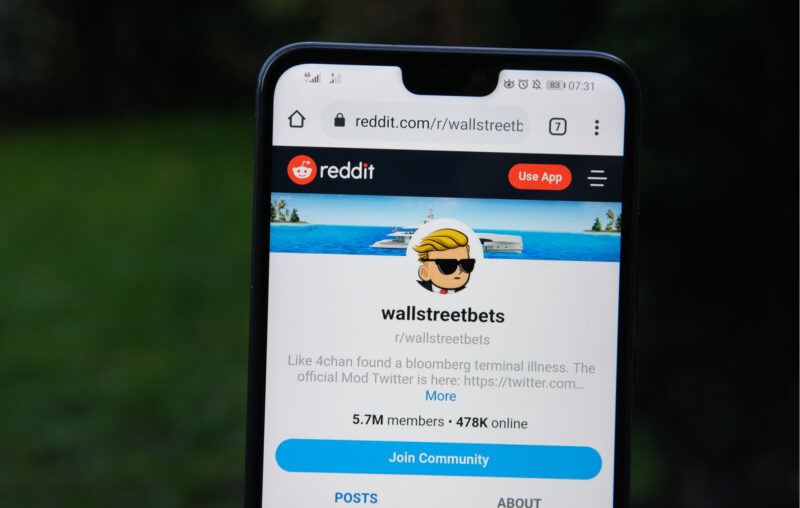

GameStop, along with Hertz, AMC and others have made headlines recently as their share prices soared in defiance of their near-death fundamentals. Crowds of traders often called a “flash mob,” mostly brash young novices, got together via social media to bid up the shares, motivated partly by the age-old prospect of selling to a greater fool, but also to “stick it to the shorts,” meaning force holders of short positions to buy the shares and cover their losses, thereby driving shares still higher, and presumably reaping a dose of schadenfreude for the mobsters along the way.

The GameStop story was the subject of Peter C. Earle’s recent piece “Who’s to Blame for the Rash of Short Squeezes?” here at AIER.

Short sellers borrow shares and sell them, hoping to buy them later at a lower price and return the shares. Short-selling is neither illegal nor immoral, and when short sellers are right they help adjust the share prices of failing companies sooner than would otherwise happen. Naked short-selling is a problem, however. Short sellers are naked when they sell shares they have not actually borrowed. Naked short selling is illegal and in fact genuinely fraudulent, yet somehow more than 100% of GameStop’s outstanding shares had been sold short at one point. How this came to pass remains a mystery, but it is a sideshow here.

The flash mob doesn’t care whether GameStop has a future as a going concern. That particular company may be somewhat familiar to them but with other shares, they seem to have no idea what the underlying company does or what its prospects might be. A mob drove up Hertz stock after it declared bankruptcy, for example. Some of the mob are so careless that they buy the wrong stock; an Australian issue with the ticker GME doubled during the chaos.

This will end badly. Of this there can be no doubt, but the timing is anyone’s guess. While the madness continues we sober observers and critics will be ridiculed—some are being tagged with the epithet “boomer.” That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t speak up, whether we’re investment professionals, economists, or just plain folk. The hard lesson that many or most GameStop mobsters will learn when they are left holding near-worthless shares may be deserved, but there will be serious spillover effects. The collapse of GameStop and other flash mob targets could trigger a broad market selloff, given that so many shares are out of line with their earnings fundamentals. A whole generation might even be put off from saving and investing. But as Peter Earle pointed out, and I agree, the recent stock market boom can be attributed primarily to Fed money-printing, something that can only continue if not accelerate as government deficit spending soars higher and higher. The lack of sports betting due to lockdowns and the advent of zero commissions surely played a role in the rise of frantic trading as well.

Bitcoin

Is Bitcoin any different from GameStop? Yes and no. Like GameStop, Bitcoin has no prospect of earnings or dividends. Bitcoin’s supply is strictly limited but as a practical matter so is GameStop’s: though they might wish for it, a secondary offering of shares by the company would be well nigh impossible. GameStop’s appeal lies solely in greater fools waiting to buy whereas Bitcoin is now taken seriously by large institutions as a promising store of value and means of payment; in short, alternative money. Bitcoin could be a bubble; GameStop certainly is. If I were a betting man, and I am, I’d say Bitcoin is in no danger of collapse any time soon and it could easily move higher in dollar terms. GameStop may already have collapsed by the time this article appears online.

Federal Money, Federal Debt

What about government-issued money and federal debt? I still have a one-dollar bill from my childhood that promises redemption in silver on demand, but the days of redeemability are long gone. Our money is backed by nothing, so why does it persist? Two reasons are often cited: legal tender laws that purport to force creditors to accept it, and the fact that taxes must be paid in government-created dollars. But the real reasons, I submit, are inertia and the network effect. Accounts are kept in dollars throughout the United States and in many places overseas. Sellers demand dollars; buyers demand acceptance of their dollars. These facts make the dollar’s purchasing power far more stable than that of Bitcoin or gold. Don’t we all think of our gains and losses in dollar terms? A shift to Bitcoin or any substitute fiat currency would entail a massive economic upheaval, though not impossible.

U.S. Treasury securities are still the gold standard of debt instruments; corporate and municipal bonds are rated for safety relative to Treasuries. Just what do you get when you buy a Treasury? A promise that you will get your money back along with periodic interest payments (excepting zero-coupon issues). Where do they get the money to pay bondholders? As long as deficits persist, it has to come from future borrowing. How long can debt continue to accelerate? A soft landing becomes increasingly unlikely as debt is piled upon debt. Default and/or inflation are serious possibilities as I argued recently in “Dry Tinder at the Fed.”

In summary, the flash mobs, coordinated as they are by social media, have created disturbing and disruptive bubbles and may continue to do so. Bitcoin is probably not in a bubble. Above all, let’s not forget the ominous longer-term debt bubble.